Mounir Fatmi (Morocco)

Photographic Art, Video Art & Wall painting

Born 1970, Tangier, Morocco, lives and works between Paris, Lille and Tangier.

mounir fatmi constructs visual spaces and linguistic games. His work deals with the desecration of religious objects, deconstruction and the end of dogmas and ideologies. He questions the world and plays with its codes and precepts under the prism of architecture, language and the machine.He is particularly interested in the idea of the role of the artist in a society in crisis. His videos, installations, drawings, paintings and sculptures bring to light our doubts, fears and desires. They directly address the current events of our world, and speak to those whose lives are affected by specific events and reveals its structure. Mounir Fatmi's work offers a look at the world from a different glance, refusing to be blinded by convention.

mounir fatmi's work has been shown in numerous solo exhibitions : in Mamco, Geneva, in the Migros Museum für Gegenwarskunst, Zürich, Switzerland, at the Picasso Museum, war and peace, Vallauris, at the FRAC Alsace, Sélestat, at the Contemporary Art Center Le Parvis, at the Fondazione Collegio San Caro, Modena, at the AK Bank Foundation in Istanbul, at the Museum Kunst Palast in Duesseldorf and at the MMP+, in Marrakesh.

He participated in several collective shows at the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris,The Brooklyn Museum, New York, N.B.K., Berlin, at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, MAXXI, Rome, Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, Museum on the Seam, Jerusalem, Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Moscow, Mathaf Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, the Hayward Gallery, London, the Art Gallery of Western Australia, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

His installations have been selected in biennials such as the 52nd, the 54th and the 57th Venice Biennial, the 8th biennial of Sharjah, the 5th and 7th Dakar Biennial, the 2nd Seville Biennial, the 5th Gwangju Biennial and the 10th Lyon Biennial, the 5th Auckland Triennial, Fotofest 2014, Houston, the 10th and 11th Bamako Encounters as well as the 7th Biennale of Architecture in Shenzhen.

Mounir Fatmi was awarded by several prize such as the Cairo Biennial Prize in 2010, the Uriöt prize, Amsterdam, the Grand Prize Leopold Sedar Senghor of the 7th Dakar Biennial in 2006 as well and he was shortlisted for the Jameel Prize of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London in 2013.

Artworks

4th Edition Al-Tiba9 Algiers 2016

the blinding light

The Blinding Light - Photographic Art

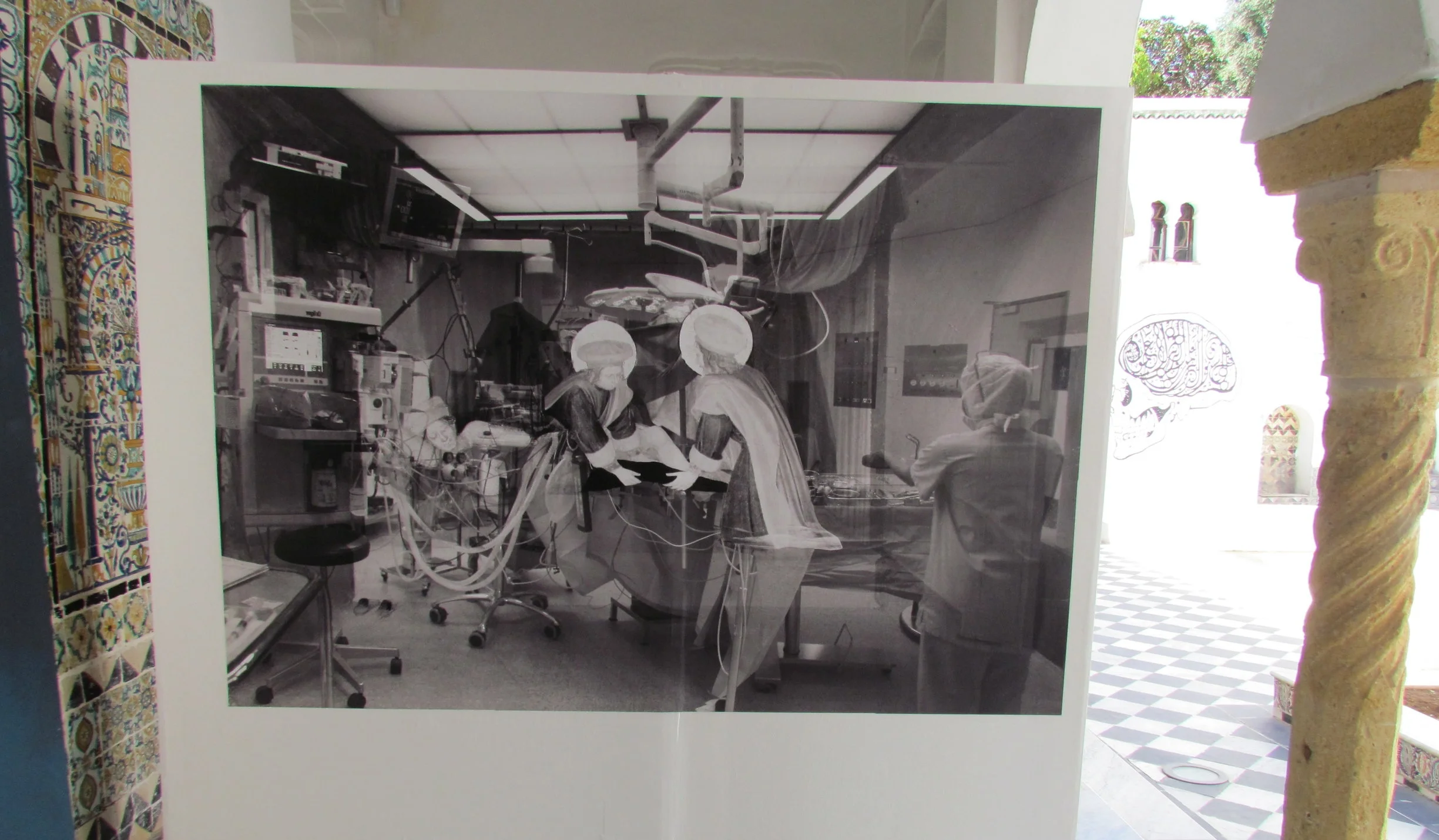

The Blinding Light is a project by mounir fatmi whose various pieces were inspired by a miraculous scene painted by Fra Angelico. The work in question, the altarpiece of Saint Mark (1440), exhibited at the San Marco national museum in Florence, shows in its predella the miracles performed by two saints, Cosmas and Damian. Patron saints of surgeons and pharmacists, these twin brothers were supposedly born in Arabia and converted to Christianity in their youth.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, they accepted no payment for their services, which led them to being named Anargyroi, or “without money”. Thus, they attracted a great number of people to the Christian faith. During the persecutions of Diocletian in 287 AD, Cosmas and Damian were arrested following the orders of the prefect of Cilicia, Lysias. He ordered them to abjure, but they remained true to their faith and were insensitive to the atrocious torture they were submitted to. They walk out of the sea despite the chains burdening them. On the pillory, they don’t feel the blows of executioners who end up collapsing from exhaustion. The flames of the stake spare them, burning the pagan audience instead. Arrows and stones revert their course to hurt those who threw them. In the end, the saints were decapitated, along with their three younger brothers.

The miracle chosen by mounir fatmi is called The Healing of Deacon Justinian. In this scene, the Arabian brothers perform a posthumous miracle when they graft on the deacon the leg of an Ethiopian man who had just been interred in Saint Peter’s cemetery. This scene evokes the mixing of a white body with a black limb, of the living with the dead and thus questions notions of race, hybridization and identity.

In the first series of Blinding Light photomontages from 2013, various photographs showing an operating room with all its technology and hygiene are superimposed on this miraculous scene. As in the video of the same name, doctors stand alongside the two saints, forming one same workgroup. In this way, ghosts and living people are present in another form of reality, a fantasized temporality that is just as miraculous as a religious text.

In 2011, in a video entitled The Black Leg of the Angel, mounir fatmi took a particular interest in this unusual graft. Over a high-pitched and ghostly soundtrack, x-rays of the painting are shown. Decomposing, recomposing and superimposing different elements of the scene, the video shows them ingenuously blurred together. As a negative of this video, another one with the same title follows the same structure but inverts black and white in the images. Playing on contrasts, that video highlights more than ever the act of grafting and echoes mounir fatmi’s entire work by alluding to questions of identity and cross-breeding.

Furthermore, in the 2014 Blinding Light video, the superimposition of contemporary operation room photos with Fra Angelico’s work brings in an additional dimension. Adding to the idea of hybridization, the video creates a clever association between the Renaissance and hyper-modernity. This temporal ellipsis, superimposing different times and spaces, brings technology and anesthetics in a world that used to be governed by divine miracles. The characters in the painting thus become ghosts. Such a discrepancy forces the viewer to mentally go back and forth between the two eras. In this way, the superimposition of epochs brings forth the idea that a religious miracle is perfectly feasible in this day and age.

Mounir Fatmi attempts here to combine in an unexpected way two spheres of beliefs that are often seen as antagonistic. On one side, science, order, reason and concreteness; on the other, religion, with its notions of faith, miracles and the sacred.

Studio Fatmi, December 2016.

Modern Times, a History of the Machine

Modern Times - Projection

A History of the Machine is a work of movement, speed and looped images whose visual style invites viewers to make ties with paintings by Sonia and Robert Delaunay, a film by Charlie Chaplin, a work by Marcel Duchamp, as well as with writing and thought. We are inside a thinking machine in all its complexity.

Nicole Gingras, in Exhibition catalogue Manif d'Art 6, 2012, p. 32.

hard head

Hard Head - Wall painting

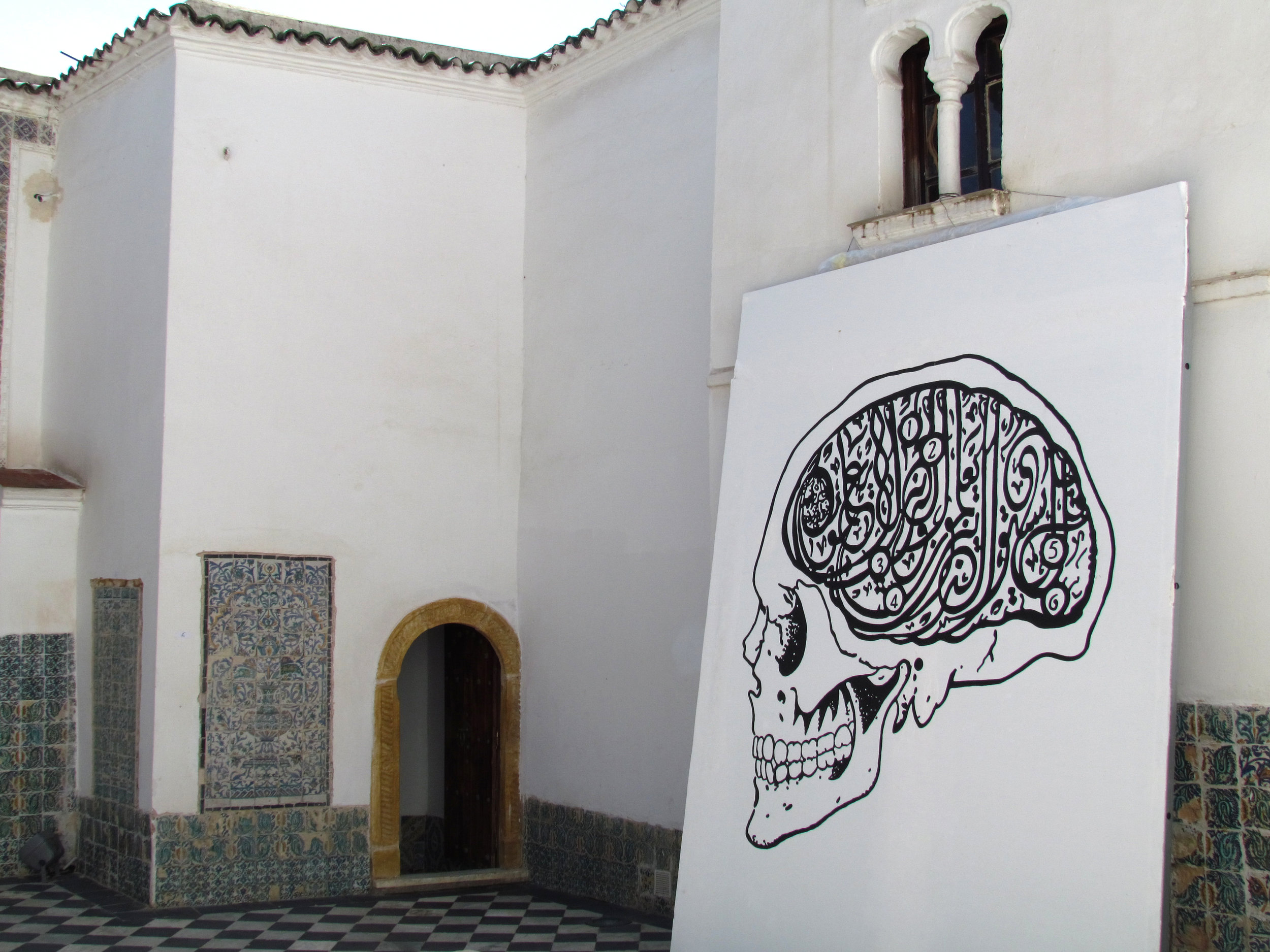

Painted on the wall, a black calligramme. The interlaced curves and countercurves encircle the numbers from 1 to 6 forming the brain inside a skull. The profile is drawn with black paint on a white background. Under his Hard Head, mounir fatmi has written the free translation of a Koran verse, partly in calligraphy: “Do those who know and those who don’t know resemble each other?”

Just like in ancient phrenology, the Arabic ciphers in Hard Head, locked up in this strange brain/ writing, might depict zones of desire, fear, hope, hate or melancholy, the ones that control memory and creativity, or that activate faith or atheism, compassion or misanthrophy, the lust for life or the longing to die. At the very beginning of the 19th century, Franz Josef Gall 2 gave the human spirit a spatial division. He considered the brain to command faith, speech and the capacity to walk, linking this knowledge to his belief in anatomy. After Descartes, who already said that ”the soul is united to all the parts of the body by the pineal gland” 3, Gall identified the ”centre of the metaphysical spirit” as the place of the spiritual in the corporal.

With this minimalist, radical mural painting, mounir fatmi skins certain representations that form our occidental or oriental/profane or religious identities.

If there is something specific about contemporary critical art, then it is certainly not that it is ”Christian”, ”Muslim” or ”Jewish”, african or occidental, or belonging to some identity that Art has claimed for a long time. There is no reason to believe that the artistic evolution is identical to the scientific one, because it would be easy to show that the parallel is little relevant. But what could really be a feature of artistic post-modernity is a certain capacity to observe truths as representations or as language games that steer a social, political and religious organisation.

Excerpt from Evelyne Toussaint's text, September 2006

Exhibition

Bardo National Museum of Algiers