10 Questions with Demian Shipley-Marshall

Demian is originally from Colorado Springs in the United States and is now based in Southend, UK. He trained as an artist at Adams State College, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts with an emphasis in Drawing, Printmaking, and Metalsmithing. He worked as an independent artist in his hometown until becoming involved with the education community, where he spent part of his time working as a substitute and volunteer teacher. He later moved to Melbourne, Australia, in order to broaden his horizons and pursue his teaching career in earnest by enrolling in Victoria University and earning a Diploma in Secondary Education. After this, Demian secured employment at a secondary school in rural Victoria. There, he taught metal and wood fabrication, art, visual communication, and design working with children ages 11 to 18. This also included units 1 through 4 of VCE for visual communication and design. He eventually became the art department coordinator. In 2016 he returned to the United States and worked as a part-time teacher at a local middle school and part-time as an artist out of Cottonwood Center for the Arts. Looking for a new direction, he moved to England and earned a Graduate Diploma in Arts and Design and a Masters in Digital Direction at the Royal College of Art in London. He now works as a multidisciplinary artist and designer that focuses on storytelling and education.

Demian Shipley-Marshall - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

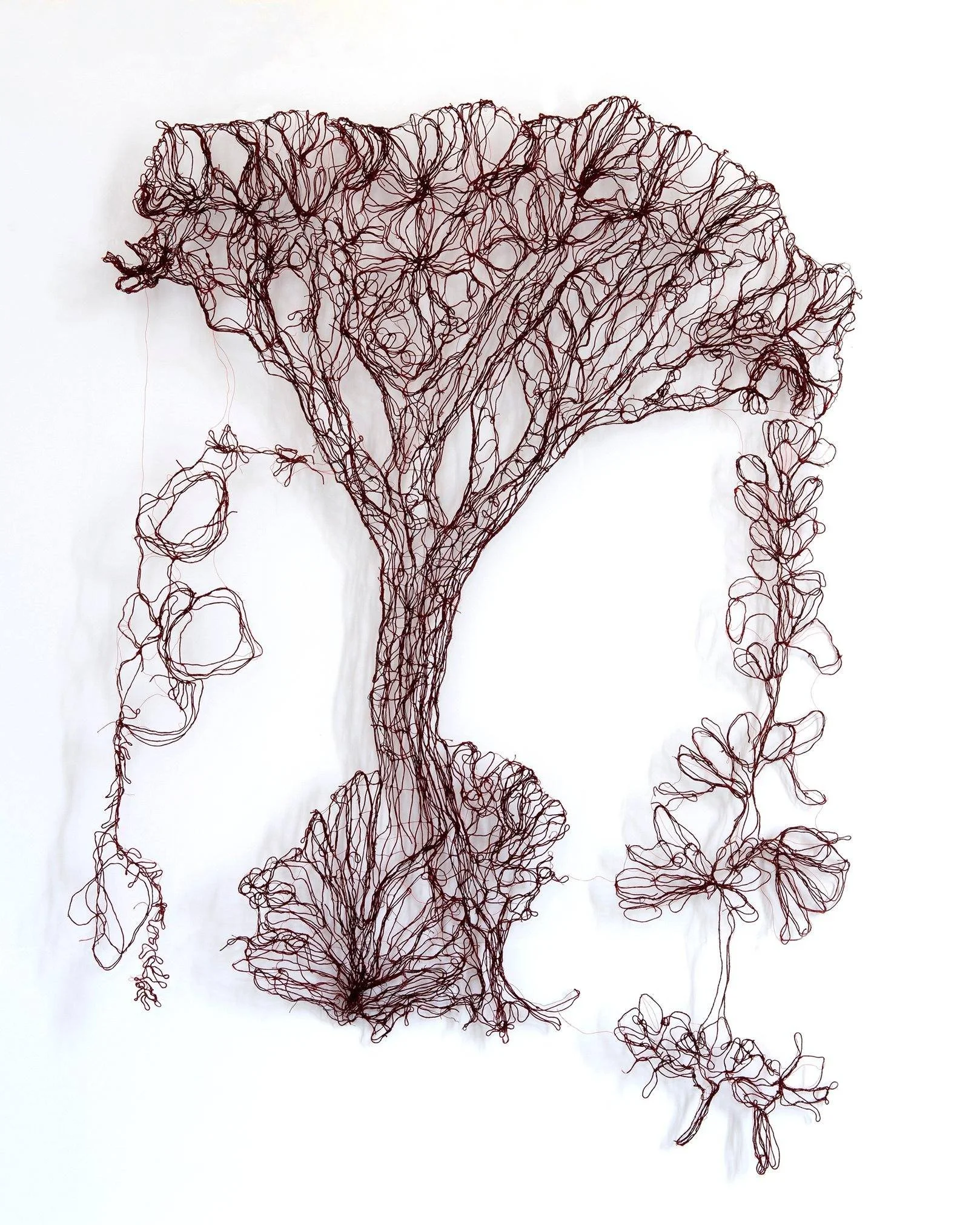

Demian Shipley-Marshall works with multiple methods across the fields of art and design but considers himself a storyteller at heart. Through his work, he endeavors to explore if older values toward the individual and environment can add new perspectives to conflicts humanity is facing in the contemporary world. Demian is influenced by world folklore, particularly stories around animals. Originally, these stories were how cultures began exploring their worlds, both real and imagined. Many indigenous cultures attributed similar characteristics to certain animals, which illustrates a deep root that connects humans to each other and their histories. Because of this, Demian believes our first teachers can still

help us navigate the turbulent waters of our future. Whatever form his work takes, it has two guiding principles: the work must always affirm life and seek truth. He does not seek to demonize our modern world, and tries to avoid the biased lens through which people often view their history. Demian wants his audience to consider that when building a better tomorrow, is it about creating a new way of life or remembering an old one?

When animals could talk Panel 2, Digital Photograph, 34x50 cm, 2022 © Demian Shipley-Marshall

INTERVIEW

You have an interesting career, between art making and education. What inspired you to follow this path? And how would you define yourself as an artist nowadays?

I have always been something of a compulsive creator, obsessed with figuring out how people did things and trying it myself, but I hated school because my curiosity had to fit into a very rigid schedule. University was better, but I was like a dog let off the leash for the first time. I was running around trying to learn every process I could: drawing, painting, printmaking, photography, metalsmithing, woodworking, and sculpting. Pretty much anything that was new and shiny. I had an impressive list of skills, but I never stopped to figure out why I created them. Looking back on it now, I can see that there was a direction of "old vs new", a fascination with animals and different ideologies shown in world folklore, but I never focused my energy on it because I would see something else shiny and take off. When I left university, I tried being an artist, but because I never really developed a practice, it never went anywhere. To make ends meet, I did temp work for a while, when that started making me miserable, I remembered enjoying an internship at an art summer camp as a teacher's assistant, so I tried my luck as a substitute teacher. I found I liked working with children. Around this time, I was invited to stay with my family in Victoria, Australia, so I decided to obtain a graduate diploma in education while I was there. When I finished my training, got a job, and got over my fear of "losing control of the class," education became like another creative process for me where I was much like a performer trying to get an audience to come along willingly with a premise. I started mingling my artwork with my teaching practice, and these days, I see myself more as a storyteller.

What training or experiences helped you, along the way, to develop both your artistic and educational practices?

I would say that for both art and education, I had to discipline myself to involve others in creative practice. I often surprise people when I say this, but I am massively introverted. Whether it's creating an art piece or designing a lesson, if I'm not careful, it's very easy for me to slip into a solipsistic state and create something in a vacuum. For designing lessons, this is obviously a fantastically bad idea. You do not know what Hell is like until you try dragging students through a ninety-minute lesson of something that you think is great but does not engage them. For art, I know that itcomes from doing a deep dive into your own head, but if you never come back out, you miss the enrichment that comes from sharing those ideas and fully exploring them. This was one of the biggest things I got from studying at the Royal College of Art, they helped me develop my practice by getting me to understand why I was creating but also forced me to go out and refine it with other perspectives. Without that, I don't know if I would have made the connections of what was driving my creativity or if I would have been reaching out to refine my practice. It was the first time that I realized I was a storyteller, and I made the connection that storytelling was the best and oldest way to educate through art.

You've lived and worked across the United States, Australia, and now the UK. How have these different cultural experiences influenced your artistic perspective?

Growing up in the United States was not a pleasant experience for me. Most across the world might be surprised by the recent political shift that is happening now, but frankly, I have to say I'm not surprised we got here. I find that people outside the US have their opinions colored by what is happening on the east and west coasts. I grew up in the massive part in the middle, where Fundamentalist Christian organizations have a lot of power and xenophobia is a common condition even though most of the population probably couldn't spell xenophobia. There is a strong tendency to follow the line David Bowie wrote in Law (Earthlings on Fire) "I don't want knowledge, I want certainty." Multiple perspectives do not give certainty, people questioning authority do not give certainty, and stories telling different narratives than we are used to do not create certainty. So, these things are actively and often brutally "discouraged". Seeing the misery these inherited systems create influenced my desire to seek alternatives in my work and created in me a desire to move. In my naivety, I thought moving to a different country would be a stark contrast to what I was leaving. I was disappointed to discover that most cultures in the modern era suffer similar conditioning, though perhaps not as intense as what I experienced. Even more disappointingly, I discovered I had not escaped as unscathed as I thought, realizing that I had my own hatreds and hangups that were not justified. However, I also discovered that these places also had a beacon of hope nestled deep in the communities, a little light that refused to go out. Indigenous cultures had survived despite the best efforts of colonization and had stories that told of a time when we lived with a more harmonious existence with our environment and individuality was not the enemy. While we may never be able to go back fully, remembering these things could maybehelp save our future. When I eventually found my way to the UK, a place many may view as the origin of these oppressive and manufactured beliefs, there were still stories and beliefs that refused to leave. In fact, there seemed to be a lot of similarities between the multiple cultures if you were willing to dig into them. That has had a massive influence on my practice, exploring one thread of humanity shows connections to other threads. You can't see these threads listening to politics or rhetoric, but you can see them through art and stories.

Your work is deeply rooted in storytelling. What initially drew you to this narrative-driven approach, and how has it evolved over time?

I remember we had a member of the Ute nation come into our school and tell the story of how Sinawav, the creator who was neither man nor woman, who was neither human nor animal, shaped the world. It was so massively different from the Evangelical-influenced narrative that usually went on in my community. It helped that I have always preferred being around animals over people, and two of the main characters in this story were Coyote and Bear. It really captured my imagination, and I got hungry for more. This was during the time when having a good librarian in your school was a lifesaver. Our school library had a lot of books about myths in different cultures, I started reading about other Indigenous American Myths, I later found a copy of "Into the West" which branched me into other cultures, and when my dad saw me getting interested in these stories he bought me an entire series of books on world folklore which I still have and consult to this day. He introduced me to Northern European folklore and showed how it influenced all the modern fiction I was into at the time. I didn't really notice it, but it started influencing my art. I would draw the characters in these stories; thenI started drawing figures and imagining them in their own stories. These had a bent towards modern fiction, and I always considered it more of a hobby, not believing anyone would be interested. When I got into college, they got lost in all the other seemingly random stuff I did. Looking back on it, though, I think I have always regarded my drawings and creations as characters in stories, even though I didn't really start piecing it together until I started to travel. It became less about just creating the characters and more about trying to let them evolve from what I was experiencing while engaging with other people. They will always be influenced by my perspective, of course, but even then, they do not always come out the way I wished they would. My body of work in The Menagerie is very much like that, the girl in The Gift, for example. There was part of me that wanted to draw more scenes with her ripping off this gilded skin she was being forced to wear, but would she though? Does she want to lose the love of her mother? Who am I to say if that is best for her? Since joining the RCA, I started working with more people to bring the characters to life. Not just as an image in my head but as a fully fleshed-out presence where the person who influenced them has a say in their creation. The Menagerie is how I start the story, seeing the character for myself; the creation of each piece influences me to create another collaborative one. For example, Dahlia influenced me to peruse the series of works in Hunting Unicorns: Life after Fundamentalism.

The Gift, Graphite, Watercolour, Coloured Pencil, and Ink on paper, 73x51 cm, 2021 © Demian Shipley-Marshall

Power Couple, Graphite, Watercolour, Coloured Pencil, and Ink on paper, 49 x 84 cm, 2023 © Demian Shipley-Marshall

Folklore, particularly stories about animals, plays a central role in your work. What is it about these ancient narratives that resonate with you, and how do they inform your artistic process?

As I said before, I have always preferred the company of animals over people; I'm often reminded of a quote from Albert Camus when I think about my fascination for animals. "Man is the only creature who refuses to be what he is". Humanity, for the longest time, has seemed determined to distance itself from its environment. Maybe this started as a desire to not be at the mercy of the environment, but somewhere along the line, it became just downright perverted. These older stories talk about times when not only did we learn things from animals, but we saw traits that they had we admired. Not just the ability to run fast or be strong, but more philosophical traits such as patience, or wisdom. So, what changed, and was it for the best? Is there a benefit to accepting our creativity while remembering we are still animals ourselves connected to ecosystems? Do our first teachers still have something to show us? Do these stories show us how similar we all are? When I first got into these stories, I made the mistake of just focusing on them one at a time. Remember when I mentioned cultural threads often lead to other threads? When you step back and start looking at how these supposedly different cultures view animals and their characteristics, there is a massive amount of synchronicity that is hard to ignore. For example, Artio is a Celtic goddess associated with bears; she is described as a protector, bringer of life, strong, and wise. In fact, her name is linked to another deity, Artaois, which is linked to the well-known Welsh warrior king, Arthur, whose crest was a bear. The Ute nation refers to Bear as the chief of the animal tribe; he is strong, the bringer of life (spring), is tasked with guarding humanity from the mischief of Coyote, and is a wise teacher. Now you could tell me to take off my tinfoil hat and say, "Well, okay, they are both associated with spring and life because of hibernation, and we know how mother bears protect their cubs, and the strength thing? Well duh, they're bears! It's not a missive leap of logic." But why though, do we associate both animals with leadership and wisdom? How did supposedly two different cultures come to the same conclusion about the role of this animal? How come they are not the only people who came to the same conclusion? All those questions, at some stage, come into my practice and become the thing that ties all my work together as I explore the world through my art.

Your practice spans multiple disciplines, from drawing and printmaking to metalsmithing and digital design. How do you decide which medium best serves the story you want to tell?

I try to match the discipline with my objectives but also communicate how I am trying to honestly tell the story. For example, in The Menagerie, the fact that these are illustrations works with the motivation of the work. They are two-dimensional; you view them through a window clearly obstructing the whole scene; the figures are faded and drawn with light graphite on white paper, while the artificial construction is drawn as realistically as I can with pigments. For me, not only does this communicate how I think we see people, only looking at the manmade skin on the surface, but also how I may be doing the same thing. This is my perspective of a person who is suffering under the contemporary system; the person on the other side of that lens may appear very different to someone else; I can only interpret what they are through my lenses, which can't see everything. If I made this as a sculpture, with real metal and something that has weight, it feels like I am making a statement that this is more real than I have a right to proclaim. Sometimes, I must start out with just what is going to work on a practical level. For example, in Hunting Unicorns, my collaborator and I knew we wanted to let a person talk about their experiences with growing up in a fundamentalist household the way they wanted to so the audience could experience them telling their own story and come to their own conclusions. The main problem with this is people currently in these communities can be targeted with hate crimes, so how do we protect their identity without losing that human connection? This led us to work with facial motion capture on Metahumans and disguising the voice with AI. Even then, we needed to consider what it means to use a Metahuman brought together with normative biased data or what other implications may distort a contributor's creativity by using "hyper-real" graphics. What other benefits can these media bring to what we are doing? Is there something else out there that can do what we want? These questions didn't come from us, but from my tutors and fellow artists at the RCA, as well as from interviews with people we have worked with. Again, going back to why it is so essential to refine this through other perspectives. It's still a body of work in its infancy, so we don't have all the answers yet, but going through that evaluation will bring us back to that original motivation of telling a story honestly, even if this means I must learn a new discipline to do it which has been the case lately.

As both an artist and educator, how do you see the role of storytelling in shaping how people, especially younger generations, engage with art and design?

That's probably best answered by a quote from Chinua Achebe, "People create stories create people, or rather stories create people create stories." The story is at the heart of every idea we ever had, and it is cyclical, with people being shaped by the stories and ideas and creating new ideas and stories that affect people. Every artwork starts with a story and creates a new story when it is displayed. Even product designers, when justifying why their design is the best solution for a need, will tell you a story on why they created it. When you consider this, I think it's obvious how you get younger generations, or anyone for that matter, to engage in art and design. I remember some of my least favorite art teachers always had one annoying trait: they would sit there and explain why a piece was good, or in other words, why I should think it was good. But for those teachers who took the time to tell the story of why, how, when, and what happened before and after, it allowed me to see the whole picture and let me come to my own conclusions. Marcel Duchamp was just a guy who signed a urinal with a silly name until you hear the story.

You ask whether building a better future is about creating something new or remembering something old. Have your projects led you toward any conclusions on this question?

The rather annoying thing about art is it mostly leads to more questions, and I think it's very rare for you to have a conclusion when finishing a piece. Even when you think you have an answer, you ask, "Was that the best answer"? Thisusually prompts another artwork, but in my experience, never a conclusion. I think the best I can offer is to say that nothing I have done has made me reconsider this as an important question. Human progress right now seems to bemeasured by how far we can distance ourselves from our ancestors. We live longer, we do less labor, and we eat more (well, some of us do), but is humanity better off, or is this going to lead us to a better future? As we look to a future where the lifestyle of a select few has stretched our environments to the point where it looks like it won't be able to support any of us anymore, are the ideologies of our ancestors who lived more harmoniously with individuality and environment looking so bad? From where I am standing, they had similar concerns about the environment, greed, loss of freedom, and a lot of other things that give us massive anxiety in the contemporary world. They were not that different from us, and they came up with ways to answer these problems. It might be worth a listen.

To see youself see me panel 6, Digital Photograph, 34x51 cm, 2022 © Demian Shipley-Marshall

Are there any new themes, stories, or mediums you're eager to explore in your future work?

The explorations we have done in the Hunting Unicorns project have led me to some exciting avenues already, but I thinkthere is a lot more to experiment with as I have become more involved with the digital space. "The Way is Back" was my first attempt at looking at the potential of storytelling in an immersive environment, specifically at Frameless in London. Even though we were not selected this time, I am still eager to see what happens when you experience that story as intended, as opposed to how it is viewed on a single screen. I'm sure this will lead to more explorations with other works.Working with Unreal Engine also opens the possibility of virtual performances in XR or making a more interactive format. Again, it will depend on whether the discipline suits what we are trying to achieve, but of course, you never know until you try it. I'm excited by the potential for my future work.

Lastly, what are your plans for 2025? Do you have any upcoming projects or exhibitions you would like to tell our readers about?

As far as 2025 is concerned, I am currently trying to find a way to permanently relocate to the UK and trying to settle into a career that will suit all my needs artistically and financially, which, as you can imagine, takes a lot of my time. However, I am currently submitting what I have done for exhibitions, and hopefully, there will be some updates on my socials soon on some exhibitions. The biggest thing we are doing right now is looking into other tools and disciplines we can use to give our contributors to Hunting Unicorns more creative freedom, and to test these, we are creating some more stories around our perspectives when looking at the ramifications of Fundamentalist lifestyles. We are always eager to listen and work with anybody who would like to tell their story with us, so if you are interested in reaching out or know someone who may be interested, please feel free to contact us through our site, we would love to work with you. Hunting Unicorns is an ongoing project, so if you are interested, please keep in touch with us to see how we are contributing to these discussions.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.