10 Questions with Eugene Ofori Agyei

Eugene Ofori Agyei is a Ghanaian-born artist and educator living in the United States. He graduated from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, Ghana, with a BA in Industrial Art, majoring in Ceramics, in 2018. Agyei received his MFA with honors from the University of Florida. He is the 2020–2021 University of Florida Grinter Fellowship recipient and the 2023 Harold Garde Graduate Studio Art Award. He was nominated for the 2022 and 2023 Outstanding Master’s and Professional International Student Awards at the University of Florida.

The artist has shown his work in both group and solo exhibitions across Florida as well as in Maine, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Ohio, Virginia, Connecticut and New York. Internationally, his work has been exhibited in Turkey and recently attracted the attention of prominent German art collector Franz, Duke of Bavaria, who acquired three of Agyei’s works and has ultimately committed to placing them in museums.

Agyei also receives the 2022 National Council on Education for Ceramic Arts (NCECA) Graduate Student Fellowship, the 2022 NCECA Multicultural Fellowship award, and the Best of Show from The In Art Gallery’s social change and open theme exhibition. Also completed artist residencies at Watershed Center for Ceramic Arts on the 2021 Zenobia Award and at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Maine on the 2022 Artaxis Fellowship.

In April 2022, the Morean Arts Center named him as one of its Fresh Squeezed 6: Emerging Artists in Florida. He is the winner of the Pathways 2022: Carlos Malamud Prize at the University of Central Florida Gallery and Rollins Museum of Art, which comes with a $10,000 prize. Agyei is the recipient of the 2023-2026 Robert Chapman Turner Teaching Fellowship in Ceramic Art at the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University.

He is represented by the Fernando Luis Alvarez Gallery in Stamford, CT.

Eugene Ofori Agyei - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

“My work explores the feeling of dislocation I have experienced through themes of cultural identity, the concept of home, material ritual, and material history. By sharing my personal experience, I aim to address the experiences of dislocation experienced by other people in contemporary society. I grew up in a family home known as an Akan, which is the ethnic group to which I belong. I am identified as a Ghanaian when I find myself outside of Ghana.

This is typically associated with Africa, but after traveling to the United States to study art, I discovered that I had adopted a new identity, which is a contrast for me. The color of my skin and how I speak have become defining features of my identity. This is how my sense of self intertwined with places, whether local or foreign, prompting questions about identity, its societal constructs, and perceptions. The idea of being perceived as a stranger became a focal point, encapsulating my experiences and offering an emotional context for my journey as a Ghanaian residing in the diaspora.

In creating the sculptures, I draw inspiration from my past to circle the square of my present, exploring my emotions while using clay between the two places I call home – Ghana and the United States. I think about art as a ritual, as a way of maintaining or challenging my multiple cultural values. My ritual begins with thinking about the feeling of dislocation, the emotions it evokes, and how I want the work to function in the space. I start with clay because it is derived from the earth; we eat out of clay, and we sleep in clay.

Clay is a medium that can capture my touch and encapsulate the emotions of living in the diaspora by sculpting ceramic using an adapted Ghanaian coil technique. I then select other materials to combine with clay through layering, cutting, braiding, and assemblage, visually capturing the impact of cultural differences. Ceramics, batik fabrics, yarns, video, and altered everyday objects are used for their complex meanings and the memories and sentiments they evoke. In my work, I use the ritual as a metaphor for the adaptability that shapes me in the face of change through cultural transformations.

Through my work, I produce a visual metaphor that conveys the essence of my ongoing diasporic journey and how it affects my identity. It invites the viewer to examine the intricate interplay between identity and place. I use my art and autobiography to articulate all these experiences and create a space for the viewer to reflect on these issues of dislocation facing contemporary societies.”

— Eugene Ofori Agyei

Searching, Earthenware clay, African batick fabric, Flag, wood, 25x45x92 in, 2022 © Eugene Ofori Agyei

INTERVIEW

First of all, why are you an artist, and when did you first decide to become one?

Being an artist has been the most satisfying thing that has ever happened to me, and seeing people impacted by my work has been a blessing. I want to share the unseen with the world and be heard.

Years ago, when I moved to the Eastern region of Ghana for my basic education, I already knew that I would someday become an artist. I recall having a fascination with making replicas of things out of items I encountered every day.

Pablo Picasso said, "All children are born artists. The problem is how to remain an artist as we grow up."

After finishing my schoolwork, I would draw cartoons from magazines. At Koforidua Senior High Technical School, my focus was visual art. I further studied ceramics in college because I was curious about it. I questioned how people could create something from nothing. I had never considered working with clay as a high school graduate who majored in graphic design. I attended my first clay class, and the way the material felt made me realize how enjoyable it was to use my hands to craft things. I became possessed by the clay, and I began creating something from nothing. I must admit that finishing this degree rekindled my passion for art.

What is your personal aim as an artist nowadays? And how did your practice evolve over the years?

I hope to leave a legacy. I want to keep creating impactful work, and exhibit while also continuing to grow as a creative person. My work has evolved over the years, moving from small-scale to large sculptures and installations. Moving forward, I employed ubiquitous culturally significant materials to express my thoughts as a contemporary African artist.

Bond, Earthenware caly, African batick fabric, yarns, 2021 © Eugene Ofori Agyei

Untiled, Earthenware clay, African batick fabric, necktie, 2023 © Eugene Ofori Agyei

You are originally from Ghana, and you moved to the United States in 2020. How did this move influence your practice?

It was a big transition when I moved to the US during the pandemic. I observed myself slide into a state of anxiety. I was checking the news constantly, as if, somehow, if I knew the situation, I could keep it under control in my mind. Despite how stressful it was at the time, I took advantage of it to sketch and do research to find my ideas. I worked nonstop as soon as I entered the studio because I had access to the materials and equipment. I began creating self-portraits and scaled them up to evoke the difficulties of adopting new cultural content while trying to maintain a sense of cultural identity and find community.

In your work, you often reflect on your identity, both from a local point of view as well as part of the diaspora living in a foreign country. Do you think these themes would have emerged in your work if you stayed in Ghana?

Interestingly, I was exploring different themes in Ghana until I moved to the US. I wasn't quite sure what I wanted my art to be yet.

Let's talk about your work. You are primarily a ceramist, but you also work with yarns, fabrics, and mixed-media installations. How do you choose which materials and mediums to work with?

I am interested in both the idea and the material quality of the artwork. I approach art making by thinking about the idea of cultural hybridity, place, belonging, displacement, what I want to create out of my emotions, and how I want the work to function in the space. I use clay to communicate the challenges of occupying these two places I call home – Ghana and the United States, as forms. I finish the forms in brightly colored batik fabric and yarn. Batik fabric is manufactured in Indonesia and printed in Ghana, and yarn is manufactured in China. These fibers are a politically charged material that is both culturally specific and representative of global exchange. To me, this is a constant rethinking of the past and present to construct the future.

Mframadan (Dewlling), Earthenware clay, African batick fabric, yarn, door handle, 72x30x30 in, 2023 © Eugene Ofori Agyei

What is your creative process like? And how did you evolve this way of working?

My process is intuitive and time-consuming from start to finish. However, it provides me the space to organize my thoughts and let the visual tensions guide me to find myself in the finished piece. To begin, I get the clay and start with the physical process of kneading. I use the coil technique that was employed by the Ghanaian women from the Akan community for centuries to make the forms to portray the values and importance of cultural elements in the diaspora. I use my figure prints as textures, and I allow those prints to be seen in my work so that the viewer can trace the creation process. I finish the forms in brightly colored batik fabric and yarn. This process involves cutting, layering, braiding, knotting, and gluing, imbuing the work with visual elements of global trade linking cultures and cultural hybridity.

What is your ultimate goal and message you want to communicate with your work?

My artwork engages dialogue about identity, displacement, and the relationship between belonging and home.

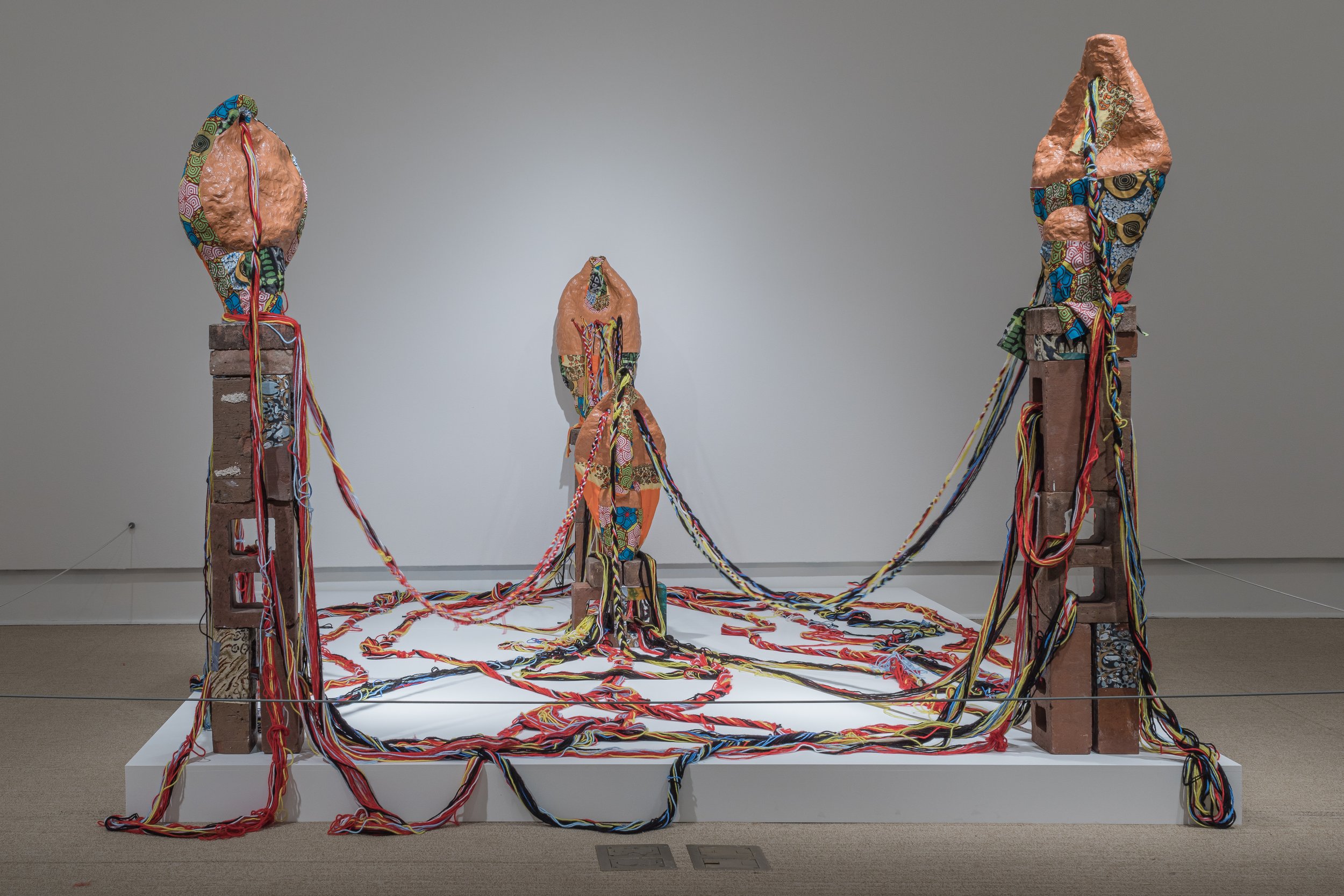

Complex Journey, Stoneware clay, African batick fabric, yarn, 90x220x440 in, 2021 © Eugene Ofori Agyei

In The Meantime, Earthenware clay, African batick fabric, yarn, wood, 110x93x212 in, 2022 © Eugene Ofori Agyei

You already work with different mediums and techniques, but is there anything else you would like to experiment with?

I'm currently experimenting with performance and video art.

You have exhibited extensively and are currently represented by Alvarez Gallery. What do you think about the art community and market?

I appreciate the Alvarez Gallery representing me. You must put in a lot of effort to stand out in the competitive art market as well as the community. There are many talented artists out there, and they all are working extremely hard.

And lastly, what are you working on now, and what are your plans for the future? Anything exciting you can tell us about?

It's an exciting time for me. I have a solo exhibition on June 1st at the Rollins Museum of Art and a three-person exhibition at the Art & History Museums-Maitland in September. I have gotten to the point where I'm pushing my work and career to the next stage. I'll continue exhibiting my work.