10 Questions with Maja Malmcrona

Maja Malmcrona is a visual artist born in 1993 in Gothenburg, Sweden. She holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in Architecture from Umeå University in Sweden and a Master of Science degree in Philosophy from the University of Glasgow in the United Kingdom. She has exhibited internationally and her work is held by collectors across Europe, Asia, and North America. In 2023, she won the Young Art Award prize at the Zurich-based gallery Art Forum Ute Barth. She is based in Zurich, Switzerland.

Maja Malmcrona - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Maja Malmcrona’s work relates primarily to an examination of space and our experience of it, placing particular emphasis on the mediation between our natural and built environment. Her work takes the form of abstract landscapes, conceptual cartography, and imaginary structures, oscillating between these overlapping yet distinct subject matters. Malmcrona believes that art should de-emphasise our societal obsession with objects and instead favour universal phenomenological experiences (over ideologies and preoccupations of the self). She uses abstraction as a tool to stay clear of an over-emphasis on these objects, being more interested in the multitude of meanings that lie behind them. In her view, the work of art is a portal—a moment in time in which we may seek emotional refuge from the overload of information prevalent in our contemporary society. Her work is grounded in modern and contemporary perspectives of art, architecture, literature, and philosophy, investigating the continuity across these fields. She works primarily in drawing, painting, and sculpture.

Interim (Theatre of No Ideas) (0287), Gouache, glue, organic pigment, pen, pencil, and tea on Fabriano paper, 76x56 cm, 2024 © Maja Malmcrona

INTERVIEW

Maja, welcome back to Al-Tiba9. What have you been up to since we last had you?

We last spoke in the fall of 2021, which is three years ago now. Besides various life changes and different severities, I have just worked: I have found new directions, abandoned some, elaborated on others, and discovered some anew. I read an interesting book by the art historian George Kubler called The Shape of Time last year. It is about viewing historical change as a linked succession of different versions of the same action, rather than a static concept of style (which is how we generally conceptualise the art historical narrative). "Artistic succession", he writes, "unfolds as a series of responses, with each new work acting as a reply to previous achievements." I find this idea quite compelling: my so-called style hasn't fundamentally changed in the last three years, and it actually most likely won't. I am still trying to achieve largelythe same thing today as I was three, five, or ten years ago—the iterations just look different and (hopefully) more refined, sometimes deviating slightly yet always heading in the same general direction.

Looking back on your recent accomplishments, such as winning the Young Art Award in Zurich, how has this recognition impacted your practice and the direction of your future projects?

Winning the Young Art Award with Art Forum Ute Barth was certainly a major milestone. It allowed me to have my first solo exhibition in an established gallery, which in turn has led to many other opportunities. To me, I think the biggest fact about recognition is just that I get to hear from a larger and more diverse group of people what they have to say about the work. Whether you like it or not, whether you know anything about art or not, I always find people's gut reactions and reflections fascinating, especially when they latch onto details that perhaps I didn't pay as much attention to myself.Sometimes these details are quite eye-opening and end up influencing the next step the project takes. In The Spirit in Man, Art, and Literature, C.G. Jung wrote that "the special significance of a true work of art resides in the fact that it has escaped from the limitations of the personal and has soared beyond the personal concerns of its creator". In other words, when the work takes on a life of its own, outside of my own thoughts about it, I know that I have succeeded with something.

Mountains Are Gentle and Seem To Smile (0296), Organic pigment on 640 g/m2 Saunders paper, 56x76 cm, 2024 © Maja Malmcrona

Let's talk about your newest body of work. As you mention in your statement, many of your pieces engage with abstraction to avoid the objectification of ideas. What drew you to this approach, and how do you maintain that balance between abstraction and narrative in your practice?

I have been working with paper all summer, which is something that seems to happen every year—all other media seem too heavy somehow, almost inappropriate. In my most recent drawing series, Mountains Are Gentle and Seem to Smile, I spent some time studying landscape paintings from Chinese Song Dynasty artists, with my goal being to understand the emotion and peculiar spatiality that they convey so beautifully. The drawings ended up being a kind of landscape, though not in a literal sense, but rather an emotional—or, more abstractly, a moral—one. But although I may view them as expressing a kind of morality, I never intend to make any specific truth-claims with them. The world is a complex place, and whenever I think of any sort of idea, I tend to see it as a sort of landscape, with (hypothetical) deep seas, tall hills, rumbling oceans and sharp cliff ledges. I am fascinated by the diversity and defiance of ideas; however seemingly self-assured, there will always be a counter-idea. Albert Camus wrote in The Rebel, "The world is divine because the world is illogical. That is why art alone, by being equally illogical, is capable of grasping it." If that's true in life, I would like to do my best to express it in my work as well.

Conceptual cartography plays a significant role in your work. Can you walk us through the process of developing these complex spatial compositions?

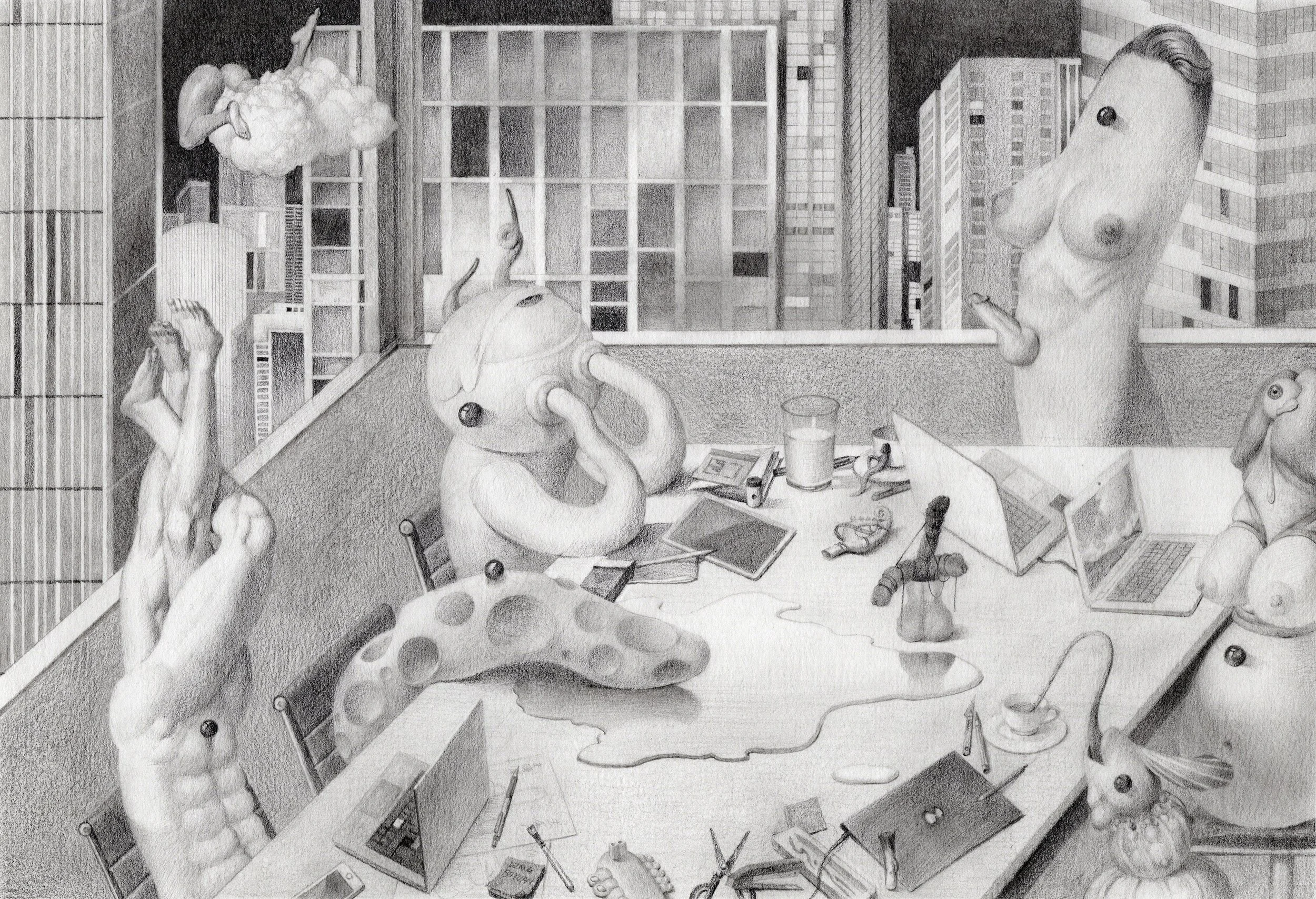

I grew up on the Swedish archipelago and was forced by my mother to learn its charts by heart, or else she wouldn't let me out to sea. I have always loved maps, but sea charts are especially fascinating to me—not only do they convey location, direction, distance, and boundaries (like most conventional maps do), but depths, hazards, tidal patterns, and so much more. Given a clear enough system, maps can contain endless amounts of information, and I find the fact that we have devised (and can universally understand) such systems fascinating. It became a type of world-building, which is something I studied a great deal in architecture school. There, the distinction between a map and a mapping is quite important: while a map offers a continuous surface description of a place, a mapping constructs a place-time discontinuity within this description, with the purpose of understanding a specified spatial condition. What I find exciting is that this spatial condition can really be anything at all, and in my works, I have tried to create mappings that explore qualitative rather than quantitative conditions. In my three drawing series Here and There (2023), Character Blueprint(2024), and Interim (Theatre of No Ideas) (2024), I looked at the perception of a home, a person, and an emotional in-between (respectively), translating these qualitative experiences into symbols which I then arranged into artistic compositions. In Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino wrote: "Signs form a language, but not the one you think you know." In other words, the way we interpret any symbolic language is perhaps not the only way to do it, and perhaps there is a lot of hidden potential—poetic or otherwise—to be found in the questioning and reinvention of these interpretations.

Character Blueprint (0261), Gouache, pen, and spray paint on Fabriano paper, 70x100 cm, 2024 © Maja Malmcrona

Here and There (0253), Gouache, pen, pencil, and spray paint on Fabriano paper, 56x76 cm, 2023 © Maja Malmcrona

You describe your art as a "portal" offering emotional refuge. Can you share an experience or moment when a viewer's interpretation of your work surprised or deeply resonated with you?

In general, any time someone looks at my work and has any kind of experience, it is valuable to me, whether it's positive or negative. One friend of mine looked at one of my larger paintings once and told me it scared him: there was something in the dark shapes that acted almost as an involuntary Rorschach test for him, and although it intrigued him, it was also somewhat frightening. Another friend described in detail the fantastic figures she saw in a different work—for her, it was like a fantasy battleground. In The Eyes of the Skin (one of the most influential books I have ever read), the Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa wrote that the "ultimate meaning" of any architectural or artistic work of art is to "[direct] our consciousness back to the world and towards our own sense of self and being" and that the "the great function of all meaningful art" is to make us "experience ourselves as complete embodied and spiritual beings." As long as the works are viewed with sincerity and open-mindedness, any interpretation that anyone may have is valuable to me.

Your work often navigates the tension between natural and built environments. How do you approach balancing these elements, and how has your perspective on this relationship evolved over time?

I think my interest in this tension fundamentally relates to the idea of chaos and order. All of us carry this dissonance within us, being at once rational and emotional, oscillating from one to the other. Dostoyevsky's two brothers in The Brothers Karamazov illustrate this, with Ivan's intellectual scepticism juxtaposed against Dmitri's intuition-driven impulses. My work oscillates between these states, too: sometimes driven by careful calculation (as in Interim (Theatre of No Ideas), 2024) and other times by emotional intuition (for example, in Compound 2, 2023). Conceptualising it as the tension between our natural and built environments is another way of expressing the same idea—the natural represents the intuitive part of our condition, and the built represents the rational one. We have drawn a strange lot, us humans, having attempted to create an environment where we control every aspect of a world that is actually completely uncontrollable. "Civilisation is like a thin layer of ice upon a deep ocean of chaos and darkness", Werner Herzog once said, and I think the challenge lies not in forcing one or the other but accepting the existence—and inevitable codependency—of both.

Compound (An Interlocutor) (0105), Mixed media on canvas, 60x80x4,5 cm, 2021 © Maja Malmcrona

Last time, we talked about your use of dark colours. How has your colour palette evolved recently? Do you find yourself drawn to different shades and hues nowadays?

The short answer is that it fundamentally hasn't changed. I still basically only use black, but it's rarely something I think about. From the beginning, I never thought of art as fundamentally having to do with colour, but rather with structure. This surely goes back to my architectural background, where colour is a secondary principle—an ornament rather than the meaning-bearing content. That isn't to say I don't admire artists who use colour; many of my favourite artists do so beautifully, and it fascinates me. But for myself, the priority lies fundamentally in structure and light.

Your background in architecture and philosophy brings a unique perspective to your art. How do these disciplines inform your artistic decisions and how you engage with space?

Fundamentally, I think my work is formally architectural yet conceptually philosophical. While the content of my work generally explores how we inhabit, understand, and think about space, the way I think and write about it is inherently philosophical—exploring some kind of foundational, non–empirical aspect of reality and perception. To me, the most fascinating aspect of architecture is that its fundamental purpose isn't so much the practice of designing buildings but rather the creation of space. In 1908, Adolf Loos wrote in an essay called Ornament and Crime: "If we find a mound in the forest, six foot long and three foot wide, formed into a pyramid shape by a shovel, we become serious, and something within us says, 'Someone lies buried here'. This is architecture." In other words, architecture is the human intervention in otherwise untouched space, and I find this idea both exciting and frightening. By and large, I think philosophy serves much the same function: it forces us to look at concepts around us that we otherwise take for granted—morality, language, our perception—and second-guess ourselves.

Let's touch upon abstraction, as your work seems to fall into that category. What are your thoughts on abstract art in contrast to figuration?

I had an interesting conversation with a friend of mine about this recently. We talked about how many of the most well-known abstract artists of the 20th century—Piet Mondrian, Hilma af Klint, Mark Rothko (to name a few)—seem to have begun in realism (or at least figuration) and only progressed to abstraction later on in their careers. My friend thought it was interesting that I didn't seem to have started there but rather moved instantly to abstraction. I thought about this for a while and realised that's actually not true—I did begin in realism; it's just that, in my case, my so-called realism was architecture. Before I created imaginary structures and conceptual cartography, I was creating actual structures and to-scale maps. However, the functional aspect of architecture (although immensely important in the real world) never interested me. My doors always lacked doorknobs, and my staircases never had any railings. To me, abstraction is much more interesting because it attempts to discover the essence of an experience by removing any superficial externals that may cloud our view. Poetry does the same thing. One of my favourite Jorge Luis Borges quotes is this: "There is an hour just at evening when the plains seem on the verge of saying something; they never do, or perhaps they do—eternally—though we don't understand it, or perhaps we do understand but what they say is as untranslatable as music…" This untranslatable in-between that is the place I am trying to reach.

Compound 2 (0214), Mixed media on canvas, 80x120x4,5 cm, 2023 © Maja Malmcrona

Sign (Primitive Architecture) (0174), Acrylic, detergent, and pen on Fabriano paper, 12,5x18 cm, 2022 © Maja Malmcrona

Stack Drawings (0273), Mixed media on Fabriano paper, 23x30,5 cm, 2024 © Maja Malmcrona

Tangent (Studies for Maps) (0228), Pen and spray paint on Fabriano paper, 12,5x18 cm, 2023 © Maja Malmcrona

Finally, what are the most significant challenges you face as an artist today, and how do you see your work responding to the evolving cultural and environmental landscape?

One of the biggest challenges we face not just as artists but also as humans is the overload of information prevalent in society today. We are bombarded by images and information everywhere, all of the time, and although this has contributed to many great things in the world, it's also taking our attention away from the present moment. We need spaces that don't try to tell us something but simply allow us to be—places that simply offer a framework for us to sit with ourselves in silence and let our minds unravel at their own pace. I believe that art, and abstract (or non-objective) art in particular, has the ability to act as this place in a very powerful way. I often think of it as a type of portal—a moment in time in which we may seek emotional refuge from the world. Of course, political art is immensely important too (especially given the state of the world today), but we also need room for the emotional, the irrational, and the phenomenological. "It isn't academic art", Olivia Laing wrote in her book Funny Weather. "It's about emergency exits and impromptu arrivals, things coming and going through the ghastly space where a person once was." The power of art lies in its ability to help us understand—or at least learn how to operate within—the incomprehensible. In the world we live in today, I find this to be an extraordinarily important task.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.