10 Questions with Sonya Bleiph

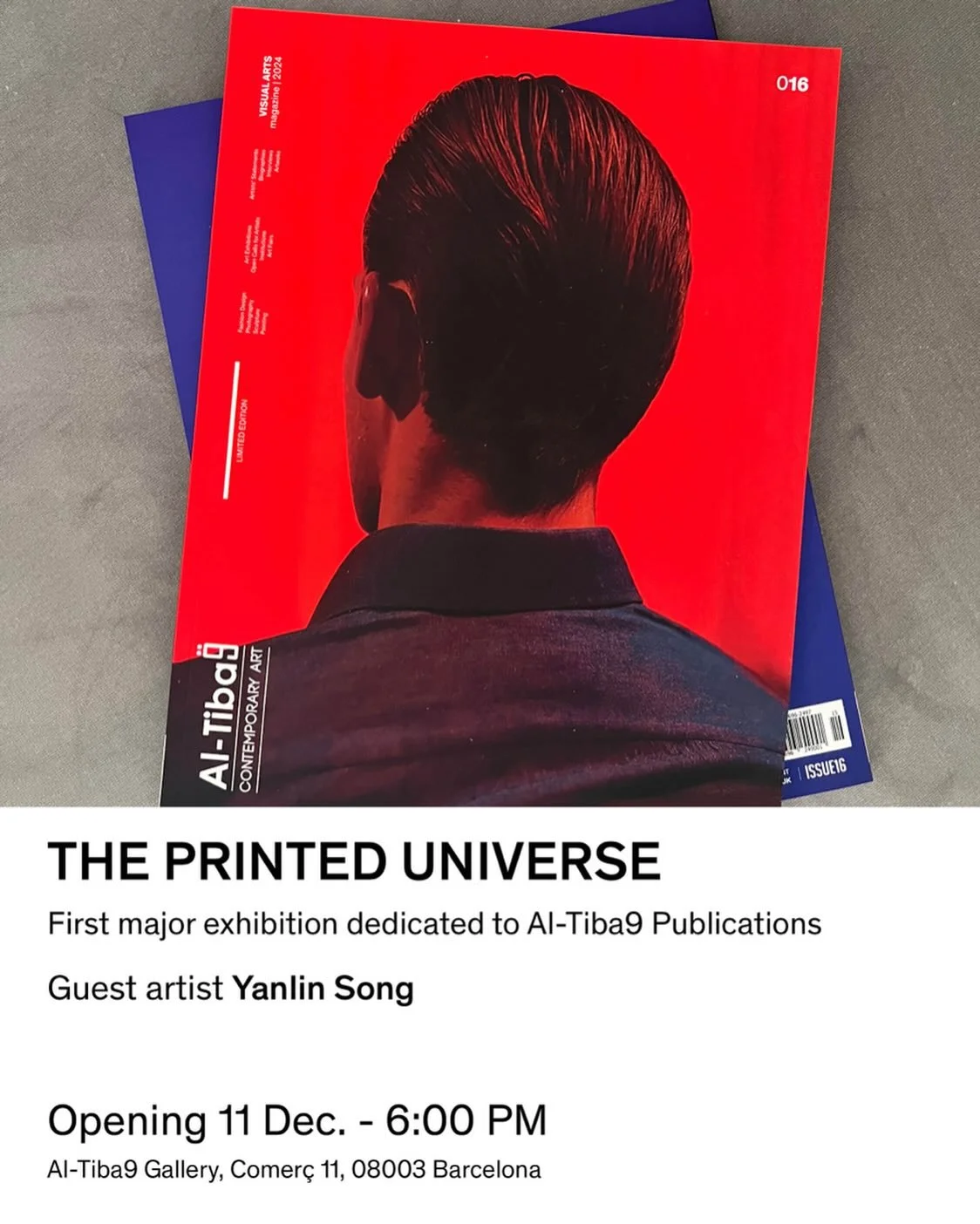

Al-Tiba9 Art Magazine ISSUE16 | Featured Artist

Sonya Bleiph is an interdisciplinary artist, creative director, and educator, working in both traditional and digital visual arts, as well as the film & entertainment industry. Bleiph obtained a BSc degree from UCL in Human Biosciences. Their paintings have been exhibited at the Other Art Fair at Truman Brewery and were awarded the Finalist Prize at Fringe Arts Bath 2022. They have recently led an immersive art show at Pushkin House in London. An art film, JCX, which Bleiph directed and produced, received an Honourable Mention at the Berlin MVA 2024. In the charity sector, Sonya volunteers as a media campaign editor at organizations supporting Eastern Ukraine. As an advocate of sustainable creative practice, Bleiph regularly works with the production company Wendyvision, where they mentor emerging LGBTQI+ filmmakers and artists. Together with Tiny Transactions performance collective, they also help bring international artists to the UK. Last August, Sonya debuted in theatre as a production designer for a play staged at Summerhall as part of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Currently, Sonya is working on a surrealist art film, in collaboration with Charlez Jimenez, Dave Harding, and Tilda Mace, amongst others, which is due to premiere in October 2024.

Sonya Bleiph - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

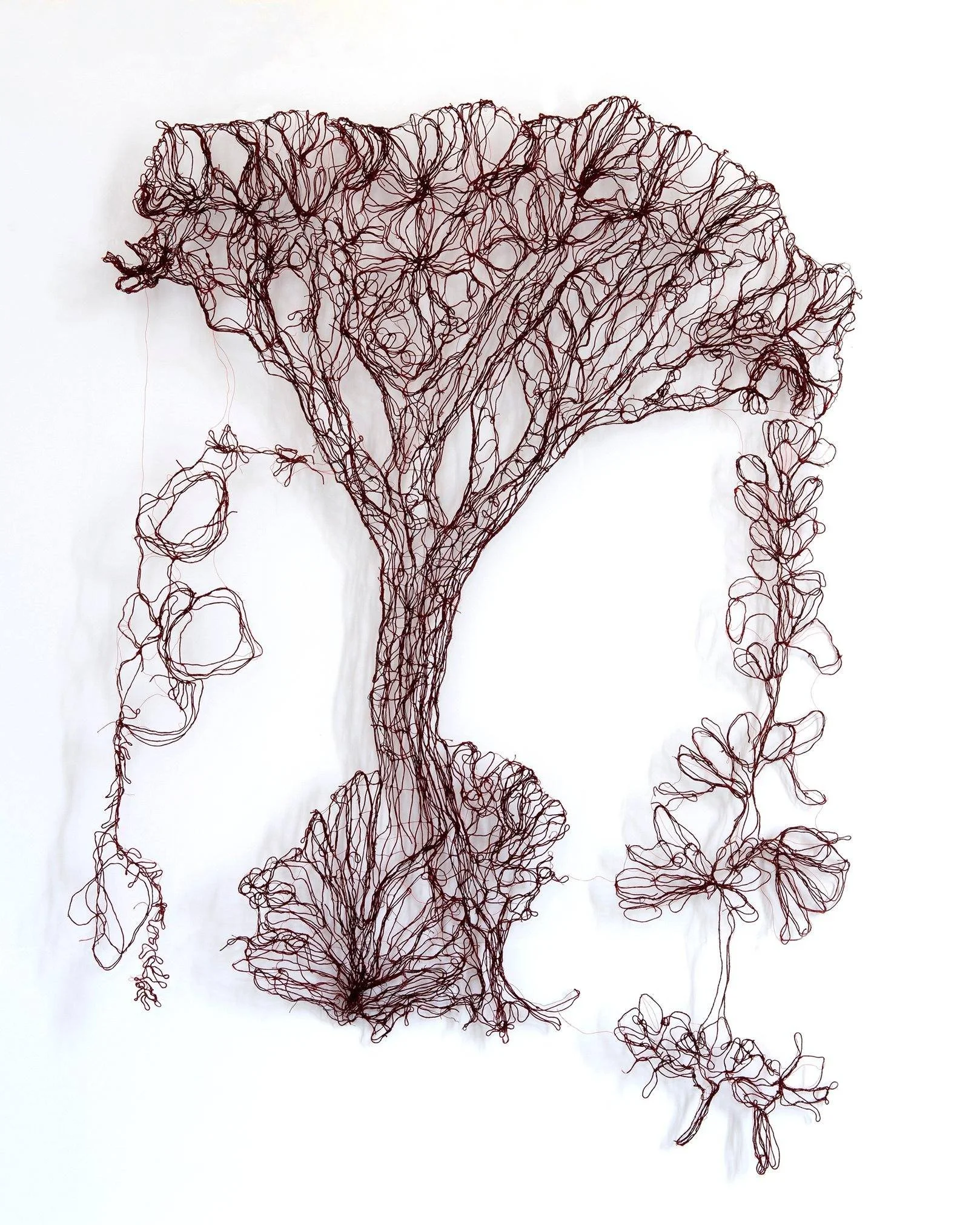

Through the lens of surrealism, industrial hauntology, body horror, and paganism, Bleiph creates an eclectic world reminiscent of the phantasmagoric. Their background in biosciences can be seen creeping into their practice; nature and industrial structures interact whimsically, and human forms contort into creatures. This otherworldly effect is achieved through working with dusty machinery, upcycled debris, and dead flora. Materials frequently featured in Bleiph's work are dilapidated trees, steel, faux fur, concrete, and decomposed plastic. Sonya's work creates an abiding motif of the awkward and disturbing, yet mesmerising and supernatural. Bleiph's recent projects focus on human inclination toward sentimentality and ritual throughout history, its reflection in contemporary mythmaking, and its interaction with modern technology.

Wyrmlands, photography and art installation, 3407 × 1897 px, 2023 © Lucky Number Music

AL-TIBA9 ART MAGAZINE ISSUE16

INTERVIEW

Please tell us more about yourself and your personal journey. How did you go from studying Human Biosciences at UCL to becoming an interdisciplinary artist?

Classic story: I've always been a weird, creative kid. As is often the case, when I was growing up, there were no examples of artistic practices that seemed sustainable in the adult world, so it never crossed my mind that I could hold any other job but an office one ("maybe marketing tho? seems to be the most creative one out of them all?")

I've been drawing and painting since I was little. Then, as a young teen, I discovered a piece of software on my dad's laptop called iMovie. Given that the Youtube sketch comedy era was on the rise, very soon I started to have fun with vlogging myself and picked up editing. This hobby, strange at the time, is now incredibly useful in my film work.

The bioscience degree seemed to be a hiccup on my journey. Very soon after starting uni though I realised how cool embryology, molecular biology, and especially genetics are. I guess I wanted to learn how transcription and evolution of genes occur because I always dreamt to turn into a mutant from the X-Men universe, and shoot up adamantium to turn into a badass supernatural creature. Additionally, I hoped that the psychology and neurobiology modules I took would train me to become Cal Lightman from the "Lie To Me" series.

In the last year of my bachelor's, on one fateful evening, I was chilling in the canteen, scrolling through my Facebook feed. That's when I saw a post of our uni's film society, recruiting crew members for the last term's film production. I thought it would be a great opportunity to meet more cool people before I graduate, so I decided to apply for the position of "Production Designer." The meaning of that title meant nothing to me at the time. But I thought I'd manage: the word"designer" appears in the job title, so… "u know, I can draw and stuff".

The next week I had to look up recipes to cook fake blood, make cocaine bricks out of plain flour and egg whites, and source sugar-glass bottles that would be smashed against a stuntman's head in my parents' bedroom that I decorated as a hotel room.

"...And people get paid for doing this????"

The rest is history :)

Ameloblast, photography and digital art, 2480 × 3407 px, 2024 © Sonya Bleiph

What initially sparked your interest in art and art making? What motivated you to turn this interest into a full-time career?

I am very lucky to have an artistically erudite family. My mum would take us all to galleries and tell me about the artists' motivations and life experiences that educated their work in a very intriguing way. She would come up with quiet games we would play in the halls of the exhibition that would focus my sporadic mind on taking in the beauty of displayed paintings. As per my practical artistic skills, I have been diligently trained by my dad and grandfather from the very second I was able to hold a pencil for the first time. Those two possessed drawing proficiency and talent equal to that of Valentin Serov. Lastly, my grandmother, who played a great part in my upbringing, had always entertained me with various handicrafts and encouraged me to experiment with different mediums (especially fabrics since she was a sewing savant).

The UK offers far greater opportunities compared to my home country. Once I realised that artists can make a living here, I didn't hesitate to turn my interest into a career.

How does your scientific background influence your artistic practice and the themes you explore in your work?

Drawing parallels between human emotional behaviour and underlying physiological processes is fascinating. For instance, understanding the neurotransmitters that are deficient in depression helped me overcome my own struggle, revealing how a lack of chemicals in your body affects your tangible experience and perception of the world and people around you. These insights, informed by my scientific background, are reflected in my work, and I hope others find meaningful connections in it.

Additionally, knowledge about human embryonic development makes it fun to explore adult attitude and physical performance, considering how early developmental stages inform the functions of various body parts (and how much could've gone wrong!)

Judas, photography and sculpture, 3407 × 1915 px, 2023 © Sonya Bleiph

Can you describe your creative process? How do you go from the first idea to the final product? And what are the fundamental steps you take to ensure each work meets your expectations?

I employ a standard ideation process: I compile references and set strict parameters for elements like colour palette, texture, and level of detail. Then, I produce a range of rough sketches. Even when I think I've created enough variations, I push myself to generate at least one more. About 30% of the initial ideas are developed further, during which I test different techniques for implementation. By this point, it's clear which option will be taken to the final stage.

It's also important to leave enough room for improv, primarily to avoid falling down into the rabbit hole of perfectionism.Taking a step back from your work also allows the process of materialising the concept to be exciting: unexpected solutions are regularly the light that illuminates the last sprint of the journey. Furthermore, I'm lucky to be surrounded by friends whose expertise I respect and admire. I often show them my work in progress for their honest assessment.

Your art often includes elements of "surrealism, industrial hauntology, body-horror, and paganism," as you mention in your statement. What draws you to these themes, and how do you blend them into your pieces?

Surrealism has long served as a potent means of addressing pressing real-world issues, offering an almost limitless array of perspectives on any given subject. A brilliant example of this is the works by the Strugatsky brothers (the authors of "Roadside Picnic" and "Hard to be God"), who used sci-fi literature and phantasmagoric metaphors to provoke discussions in societal contexts where such debates are otherwise suppressed. Industrial hauntology serves as a bridge between the surreal and the tangible reality of my upbringing, marked by massive, eroding brutalist structures and the ghostly presence of past regimes and ways of living/thinking that seem to permeate all walls.

As the saying, often mentioned at the Edinburgh Fringe, goes: "Speak about what you know." In my practice, body horror fulfills two key functions: 1) it provides a lens through which I can integrate my knowledge of human anatomy and physiology into my art, and 2) it creates an opportunity to explore and discuss themes of gender and transient existential states, much like its use in the classic manga.

Crude Oil, photography and digital art, 5996 × 5996 px, 2024 © Sonya Bleiph & Adam Pietraszewski

Sweat, photography and digital art, 3775 × 3705 px, 2024 © Sonya Bleiph

Your work also frequently features materials like dilapidated trees, steel, faux fur, concrete, and decomposed plastic. How do you source and select these materials, and what significance do they hold in your art?

In my artistic practice, I prioritise the upcycling of discarded materials and objects, driven by two key motivations. Firstly, I am dedicated to transforming what is traditionally viewed as "waste" into something mesmerising. Secondly, I believe that materials like partially decayed bark used plastic egg containers, and bits of fur torn from old jackets carry their ownprofound histories. By incorporating them into my art, I aim to respectfully extend their narratives, adding a layer of retrospection.

These materials are not only significant for their stories but also for their symbolic value. Steel and concrete, for example, reflect the industrial themes prevalent in my work, echoing the stark urban decay echoing post-soviet culture of my home country.

As for sourcing these materials, I have found residential areas to be treasure troves for wood: bed frames, wardrobes, and chairs are often discarded near apartment block trash bins. I make sure to get there before the waste management does. Tyres and metal parts of machinery can be found in the skips of auto repair shops. If you approach the business respectfully, they will be happy to give you permission to rummage through their discarded stock. For plastics, I collect the containers from our household food purchases, clean them, and vamp them up with my heat and glue guns.

Ultimately, what do you wish viewers can experience when encountering your work? What messages would you like to convey?

Simultaneous firings in the medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Find beauty in intimidation

You've recently debuted in theatre as a production designer. How was this experience different from your work in visual arts and film, and do you plan to continue working in theatre?

In theatre, the demands for structural integrity and continuity are significantly higher compared to film. For instance, on a film set, temporary solutions like taping a picture frame to a wall might suffice for a short take. However, in theatre production, once the lights go up and the play begins, every element on stage must be securely in place. There's no opportunity for mid-performance adjustments. The cherry on top - theatre sets often need to withstand the rigors of touring (including numerous setups/takedowns) and logistical demands that always seem to be against you. All this must be managed within the usual constraints of tight budgets, demanding innovative, cost-effective, and time-efficient solutions.

In brief, theatre requires meticulous preparation to ensure the durability and correctness of every set piece and forces you to generate clever engineering solutions. So, I'm eager to participate in theatre productions more often to hone my practical skills. I truly believe that if a set designer can do good theatre, they can pull off any film set.

King Gennadi, tree trunk, newspapers, refuse bags, fur fabric, misc materials, 95x95x80 cm, 2024 © Sonya Bleiph

Can you share any details about your upcoming surrealist art film? What can audiences expect from this new project, which will premiere in October 2024?

'Transmutation,' is an audio-visual exploration of monstrous androgyny and the metamorphosis of the body. Audiences can expect a hypnotic narrative featuring celestial characters transforming into mythological beings, captured on 16mm B&W film and set to an original score by the Guildhall Orchestra. As a Producer, I worked alongside a magically talented artist Charles Jimenez, who wrote and directed 'Transmutation'.

The film unfolds through a series of monochromatic vignettes, creating a visual spell that blends the textures of celluloid for a dream-like quality. Inspired by the magic of early cinema and surrealism, we all brought together our unique artistic expertise from different fields to create a cinematic ritual that conjures a spell more than it tells a story.

In brief, expect slime, supernatural prosthetics, and fire.

Lastly, what is one piece of advice you would like to give to an emerging artist?

Respect your colleagues, team mates and fellow artists that you get along with, and help each other out.

If you make this a competition, you will find it very difficult to grow. Make it a continuous collaboration and knowledge exchange. Thus, you can become more than you could ever have been if you had been alone on this journey. As a bonus, you get to work with fantastic people, who you can always learn from and also have fun while doing your job.