10 Questions with Syl Arena

Syl Arena (Phoenix, Arizona) is a California-based artist known for his explorations of non-representational photography. He freely admits that he is addicted to color and shadow. In his current series, Constructed Voids, Arena deconstructs white light into vibrant hues and mixes them onto monochromatic constructs. Through the intersection of light, construct, and lens, Arena finds transformative relationships that he describes as “inner landscapes.”

Arena is also greatly interested in commenting on the loss of the image-object in our screen-based world. Increasingly he positions his photographs as objects rather than merely as images. To this end, the Constructed Voids are hung as bare sheets of chromogenic paper in a manner that bends the prints outward from the wall and allows them to undulate gently.

Arena earned an MFA from Lesley University (Cambridge, Massachusetts) and a BFA from the University of Arizona (Tucson, Arizona). He has taught workshops for Maine Media Workshops, Santa Fe Photographic Workshops, the Rocky Mountain School of Photography, and at events in Brazil, Canada, Cuba, and Dubai.

Syl Arena

Constructed Voids | PROJECT DESCRIPTION

Syl Arena’s Constructed Voids step into the spaces of the in-between. One can gaze upon these photographs and wonder if their metaphor represents spaces inside of us or if the metaphor points to our presence inside of a larger multiverse.

These Voids merge mystery with spectacle in a manner that queries expectations of the contemporary photograph. Arena positions them as ethereal landscapes—sublime, yet otherworldly—and embraces the idea that their visual ambiguity invites interpretation. To that end, their titles (Parna, Quin, Amsu, Jern) are fabricated words intended to strip away narrative connotation and encourage meditative consideration.

Many mistakenly see these photographs as computer-generated. Certainly, they appear to contain non-photographic qualities—deeply saturated colors, shifting figure-ground relationships, shadows that randomly change hue, and zigzags that suggest glitches in digital code. Such misconceptions speak volumes about the desire to see truth within photographs.

Their visual truth echoes the spirit of many Bauhaus photographers in that these images originate as tabletop constructs of paper, plastic, glass, and metal; the glossy materiality of which provides form and reflection. Arena does not strive to make photographs of scenes before the lens. Revealing the specificity of assembled materials is not of interest. Rather, Arena strives to create photographs of scenes that we cannot see.

California Dreaming © Sue Vo-Ho

GET YOUR LIMITED EDITION PRINT >>

INTERVIEW

Introduce yourself to our readers. Who are you, and how did you start experimenting with art?

Hello! My first name, “Syl”, rhymes with “Bill.” It’s short for “Sylvester”, which was my grandfather’s name. Like him, I have red hair, although mine borders on crazy red hair most days. I’m descended from generations of Italian farmers. As a youth in Arizona, I worked on the farm for many summers and, for several years after college, farmed cotton and wheat with my father. Although that was decades ago, this heritage informs my ongoing connection to creation, growth, harvest, and regeneration.

From my earliest years, I have always identified as being a creative maker. The alchemy of darkroom photography captured my imagination as a youth; a fascination that I continue to embrace today. While earning my BFA (University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona) near the end of the 20th- century, I explored modernist and alternative photography. After my family stint as a farmer, my career wandered for several years, eventually settling down to work as a freelance photographer for a decade—with specialties in environmental portraiture and product photography. This work fulfilled the needs of clients rather than express my personal ideas.

In 2013, I accepted a full-time position teaching art. My induction as an educator catalyzed my return to focusing on the creation of personally significant art. After completing my MFA in 2017 (Lesley University, Cambridge, Massachusetts), I continue to pursue my passion for analog and digital photography across an eclectic range of projects. Today, I live in a semi-rural area of California, about halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

What is your aim as an artist?

Through the Constructed Voids, I strive to create aesthetic experiences that invite the viewer’s meditative consideration. In the best moments, one detaches from the present and wanders through the work. In so doing, various thoughts and feelings will emerge. In this regard, I seek to be a catalyst rather than an arrow that points to a destination.

I intentionally present space and scale on an ambiguous basis. Yet, my addiction to color and shadow is evident. While the former may seem obvious, the latter deserves explanation. Light illuminates, but shadows reveal shape, texture, and depth.

I see this dichotomy as indicative of western and eastern philosophies of photography. You may be familiar with the entomology of “photography” from the Greek φωτογραφί “fotografia”—which translates literally into “light writing.” Contrast this with the richness of the seemingly contradictory view offered by traditional Mandarin where the word for photography— 摄影 —is the concatenation of two characters—摄“shè” and 影“yĭng.” “Shèyĭng” literally means to “take in shadows.” That photography can be seen both as “writing with light” and as “gathering shadows” provides a rich source of creative inspiration.

Although I am not a poet, I once impulsively penned a short poem that expresses the mysteries I encounter through the idea of gathering shadows in the Constructed Voids.

In the void that is our universe, darkness shines.

Nothing can be seen until light races in to push out the blackness.

Yet, light remains invisible, unseen as it flies past.

Our experience of sight is only that of perceived reflections.

Nothing is visible until light bounces off the surfaces that exist within the void.

Although the blackness appears to retreat, it remains,

waiting patiently to again fill the void.

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Your “Constructed Voids” are ethereal and ambiguous landscapes, almost abstract works, where the viewers can immerse themselves. How did you come up with the idea for this series?

Much of my artistic life today is inspired by my miraculous survival of a typically fatal brain aneurism five years ago. During my two weeks in the neuro-ICU, through the combined effect of my injury and the intense medications, I frequently hallucinated fields of swirling lines and undulating patterns. I came to see these visions as internal landscapes. Fortunately, I am among the tiny minority of survivors who carry no physical disability. Rather, my ongoing challenges have been internal. The healing of my brain, the remapping of my neural connections, is an evolving process in which I am both the participant and a spectator.

In this context, my Constructed Voids step into the spaces of my in-between. I gaze and wonder if their metaphor represents spaces inside of me or if the metaphor points to my presence inside of an infinite multiverse. Occasionally I dare think that there is no distinction between the two.

As art objects, the Constructed Voids merge mystery with spectacle in a manner that queries expectations of the contemporary photograph. I position them as ethereal landscapes—sublime, yet otherworldly—and embrace the idea that their visual ambiguity invites interpretation. To that end, their titles are fabricated words intended to strip away narrative connotation and encourage meditative consideration.

Viewers often look at the Constructed Voids and mistakenly describe their non-representationality as abstract. To create an abstraction is to focus one’s view by extracting a part from a larger whole. Siskind abstracted. My photographs point to the antithesis of abstraction. As I will explain shortly, they are the tripartite merger of deconstructed light, ambiguous substrates, and the vision of a contorted camera—a concretion of a reality that does not exist until I externalize the void within.

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

What do you see as the strengths of your project, visually or conceptually?

Although not among my initial objectives for the work, I have come to accept that my Constructed Voids are implicitly confrontational. To start, many never get past the intensity of the palettes and, thereby cannot engage with the work at a deeper level, for which I make no apology.

The Constructed Voids decidedly confront the common expectation is that photographs convey truth through mimetic representation. While there are clues in the works about the nature of what was photographed, creating photographs as documents is of no interest. In the studio I often lose my way when looking at the image on the back of my 4x5 camera. I literally have to reach out from behind the ground glass with a long stick and touch the object being explored in order to understand what the camera is seeing.

In foundational drawing classes, there is the classic exercise where an attempt is made to copy a line drawing right-side up and then upside-down. The common result is that the upside-down drawing is more faithful to the original because the analytical mind walked away from the lack of visual logic and, in so doing, enabled the creative mind to step forward. I find great resonance between this experience and that of viewing the Constructed Voids. If one only looks for evidence and visual logic with an analytical mind, one’s consideration will be short-lived and disappointing. Conversely, if one engages with the Constructed Voids through an unstructured consideration, seeing what one will see and thinking what one will think, without the expectation of logical comprehension, then one will discover that personally significant engagement emerges.

I also feel fortunate to have come up with the series title “Constructed Voids.” For some time, I did not see this paring of words as an oxymoron. I continue to reflect on the tension between the nature of constructing and the nature of a void.

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Another key theme in your series is the “loss of the image object in our screen-based world.” Where do you see photography going in the future? Do you think the digital will prevail on the physical objects?

The Constructed Voids literally bow outward as image-objects. They are exhibited as bare sheets of chromogenic paper (96cm x 140cm) with internal frames that hold the edges of the prints perpendicular to the gallery wall. Viewers are often surprised to find that these photos curve outward into space. Further, the unsupported surfaces undulate gently under the gallery ventilation or the poke of a curious viewer. When one walks closely past, the wave of displaced air makes the prints rumble. I enjoy these reminders that experiencing a photograph as an object differs greatly from seeing it as an image.

However, there is no doubt that the majority of photography’s future will be digital until technology comes along that replaces digital. Most of my students do not remember their lives in a pre-iPhone world. While I remain concerned that their primary engagement with creating and viewing photographs happens on the small devices that are incessantly in their hands, I have accepted this as a quantum shift in the idea of “being creative.” The ubiquity of mobile technology and social media has given birth to new forms of intangible artistic expression, the significance of which will only manifest through hindsight.

That said, I expect that I will always be among those who continue to immerse themselves in photography as a means of hand-made expression—both in the making and in the experiencing of the work. When I begin to doubt the validity of the idea that handmade work will continue to have relevance in an increasingly digital world, I remind myself of the disconnect between watching the preparation of a great meal on YouTube and the depth of experience gained from actually preparing the food and then eating it. Authenticity of experience is increasingly important to me as an antidote to our digital engagement with the world and each other.

Your works are complex and layered pieces. What is your creative process like?

The Constructed Voids echo the spirit of many Bauhaus photographers in that these images originate as tabletop constructs of paper, plastic, glass, and metal; the glossy materiality of which provides form and reflection.

A trio of stage fixtures deconstructs light into projections of primary colors. Where two hues merge to create a third, shifts in perceived depth occur when the interference of the construct’s edge casts a shadow that reveals just one of the parent colors. In more recent works, substrates create mystery by absorbing light internally and radiating it elsewhere.

Many mistakenly see these photographs as computer-generated. Certainly, they appear to contain non-photographic qualities—luminous colors, shifting figure-ground relationships, shadows that randomly change hue, and zigzags that suggest glitches in digital code. Such misconceptions speak volumes about the desire to see truth within photographs.

In the Constructed Voids, I do not strive to make photographs of scenes before the lens. Revealing the specificity of assembled materials is not of interest. Rather, I strive to create photographs as anti-documents that offer connections to unseeable spaces. I intentionally break the parallel relationship between lens and image plane by stretching and contorting the two ends of my 4x5 view camera. With the lens looking in one direction and the image plane looking in another, my photographs portray scenes that exist beyond the horizon of human vision.

The means of capture also adds context to the work. My circa-1997 digital scanning back requires many minutes for the sensor to move across the back of the camera. Thus, when a lightweight construct vibrates under the heat of the lights, the moving edges are recorded as zig zags. I see these as a reminder of time’s flowing nature and as further evidence that the Constructed Voids portray a world that I cannot see directly.

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

What artists and photographers influence and inspire your work the most?

I draw inspiration from an eclectic range of sources—both within the world of art and across the universe. As a point of beginning, the experimental constructs of László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) provide motivation to create and explore my own constructs in the studio. Early inspiration for the Constructed Voids also emerged from the mysteries I see in the photographs of cut paper by Francis Bruguière (1879-1945) and Frederic Sommer (1905–1999).

Of equal resonance are the contemplative depths I find in the still life and landscape photographs of Paul Caponigro (b. 1932). Caponigro’s statement “Calm and inner stillness are for me essential companions to the activity of my craft” (The Wise Silence, 1983) provides an important tonic during moments of creative anxiety.

I continue to be deeply inspired by many practitioners of cameraless photography. Without the objectivity of the lens, they reinforce the idea that photography need not represent the world as we see it (or as we wish it to be). Lotte Jacobi’s (1896-1990) Photogenics demonstrate the elegance of pure light and shadow. The corn syrup works of Henry Holmes Smith (1909-1986) engage me through their color and form. Walead Beshty (b. 1966) cast light directly onto sheets of crumpled or folded paper and harvested colors that always inspire. Mariah Robertson (b. 1975) feeds both my addiction to color and my quest to present the photograph as something more than a flat work enshrined in a glass-topped coffin.

Eileen Quinlan (b. 1972) has kindly shared insights about her studio practice over many years. Across her oeuvre, I find art that simultaneously challenges and nurtures my ideas about the ontology of the photograph.

I have learned much from light artists as well. The recordings of Lumia created by Thomas Wilfred (1889-1968) on his Clavilux light organs provides great connection to the mysteries of color and space. Likewise, experiencing the works of James Turrell (b. 1943) and Dan Flavin (1933-1996) in galleries and museums always invigorates my desire to engage with perception at a deeper level.

I am equally inspired by random encounters with works by unknown scientists. Interstitial views of microscopic cells, macro photos of scales on butterfly wings, and deep space images of distant nebulae all whisper to me.

Do you have an essential philosophy that guides you in your creative expression?

In the aftermath of my aneurism, I learned that much of my ongoing recovery is based on inner calm and compassion—for myself and others. Understandably, these traits proved essential to finding a path forward through the pandemic. While my ego continues to rise up and assert itself loudly on occasion, for the most part, I am tuned in to nurturing my, as Caponigro wrote, “calm and inner stillness.”

I have long believed that the universe speaks to me and that the challenge is to be quiet enough to hear the message. Through this philosophy, I have strongly grasped onto the importance of discerning resonance in my life—of connecting to ideas and opportunities that truly matter and letting go of those that prove to not be nurturing. For me, this process takes considerable time—not in the doing, but in the allowing it to happen.

While I might initially think that my strongest ideas are flashes of genius, I typically come to understand in retrospect that I wrestled with them for some time. All of this is to say that creating the space within to allow for the gentle accumulation of inspiration is a significant aspect of my creative process.

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

We all miss a lot of things from our lives pre-Covid. But is there one thing that you have discovered over the last year that you will keep with you in the future?

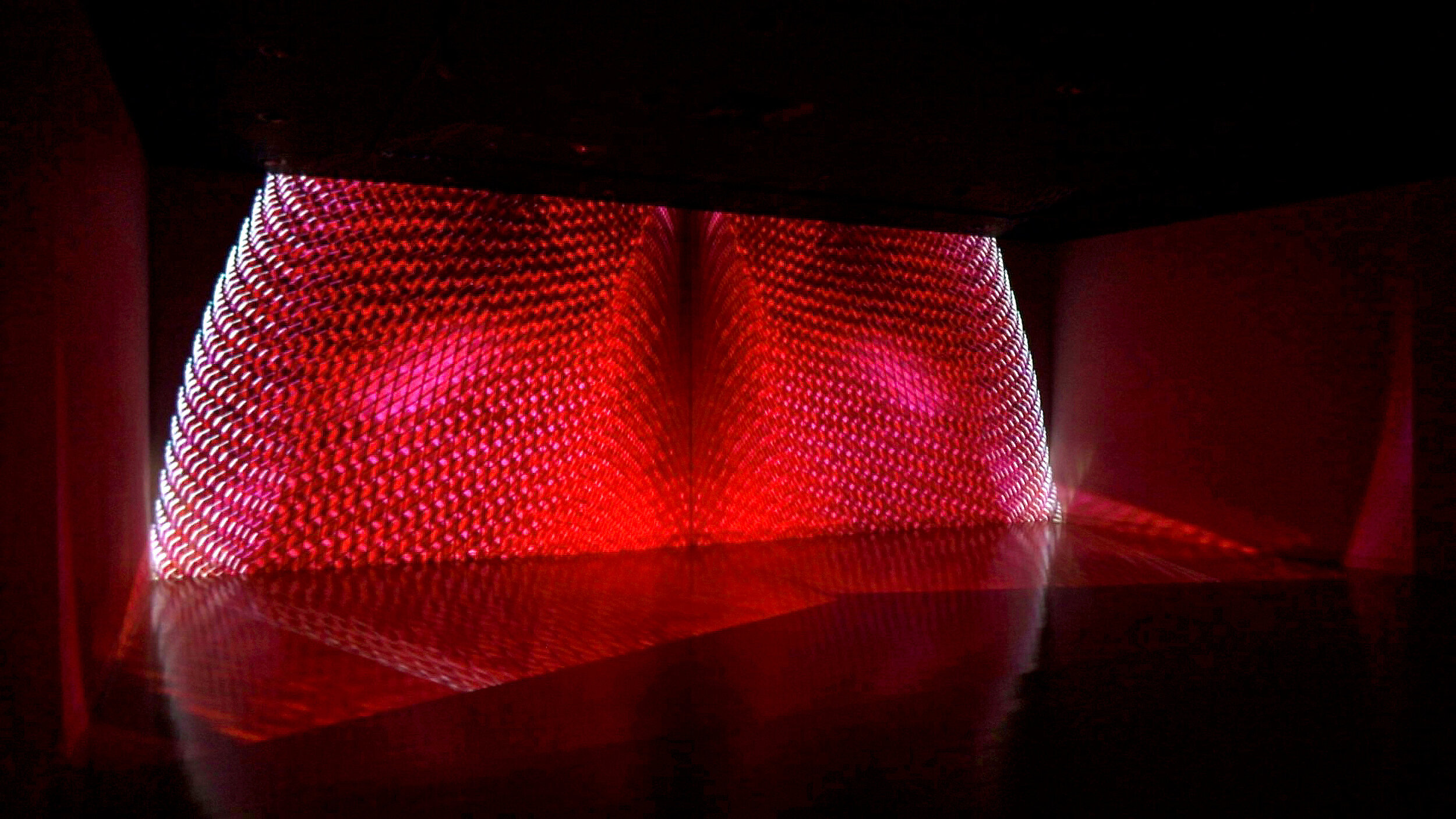

The duress of the approaching lock-downs last year gave birth of a new body of work that was completely unexpected. The Constructed Voids were to be the subject of a university solo exhibition in March 2020. When I arrived on campus, it became evident that hanging a gallery exhibition of prints in the planned manner would be futile in that the university was on the verge of announcing its lock-down. Still, as the campus was not to close until the day after my gallery opening, I wanted to present something for the benefit of the students. Through three days of intense experimentation and collaboration with my dear friend, Jer Nelsen, the Constructed Voids evolved into an entirely new body of work, which I dubbed the Projected Voids.

Using one- and two-channel video projections, we animated the floors, walls, and ceilings of the gallery spaces with the Constructed Voids. I discovered that adding movement and mirrored reflection created immersive environments that evaporated boundaries. Both gallery and viewer merged into the work.

After years of thinking about starting in video art, the pandemic pushed me over the edge. Now, I see a vast field of discovery that awaits my exploration. Rather than just animate and project my Constructed Voids, I intend to create works specifically as Projected Voids.

What are you looking forward to in 2021?

I embrace the theory that we are now heading into the ‘Roaring Twenties’ of the 21st-century. Just as the ‘Roaring Twenties’ a century ago were the reaction of years of global malaise, I expect that we will see an explosion of expression and consumption as the pandemic loosens its grip on our lives. This sense of optimism has fueled an explosion in my creativity. I have already created more work in 2021 than I created across the breadth of 2020. I look forward to this spirit of optimism and creativity spreading around the globe.