10 Questions with Anrike Piel

Working predominantly with oil painting, clay, and photography, artist and social justice advocate Anrike Piel (b. 1993), with womanhood in focus, contributes her perspective on the enduring impact of intergenerational trauma on individuals and society, the plight of refugees, and societal reflections.

Despite being born in the challenging circumstances of post-Soviet Estonia, an innate curiosity fueled dreams of a world beyond immediate reality. As a first-generation Estonian with unrestricted travel, she left home at an early age to pursue a career in fashion photography in some of the world's most vibrant cities. A decade later, after volunteering at refugee camps, Anrike's perspective shifted. The superficiality of fashion was replaced by a deeper understanding of injustice and the absence of peace. At 27, painting became her chosen medium for self-expression.

In 2017, Anrike founded "Peace in Exile," a project providing a creative sanctuary for young refugee women and girls residing in refugee camps in Lebanon and Greece. Using donated fashion from across Europe or renewing second-hand clothing, the participants fostered roles as designers, makeup artists, and models. The resulting photos redefine the term "refugee," symbolizing perseverance and strength while shattering media stereotypes.

Artistic influences draw from renowned women artists such as Alina Zamanova, Nadia Waheed, and Alymamah Rasheed, as well as resilient individuals fighting for freedom like Gazan journalists Motaz Azaiza, Bisan Owda, and Plestia Alaqad.

A significant artistic endeavour was the creation of a traveling exhibition for the Estonian Refugee Council, titled "Wolf in Sheep's Clothing: Sexism and Exploitation in the 21st Century Refugee Crisis." Based on experiences assisting Ukrainian refugees in Estonia, the exhibition reflected society, shedding light on both collective pride and underlying prejudice.

As Anrike Piel continues navigating the intersection of art, justice, and equality, her work aims to catalyse change, challenge perceptions, and advocate for a more empathetic world.

Anrike Piel - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Staying present and looking ahead in life is much simpler than delving into the question of why I am who I am. However, as the harsh reality of human rights abuses came into focus for Anrike Piel, it shattered her rose-tinted glasses. Advocacy resulted in burnout, subsequently leading to depression, which in turn necessitated an introspective evaluation of her own history. It was then that she realized she had been neglecting the core of her identity by not acknowledging why she is who she is…

In 2017, Anrike volunteered at a refugee camp for the first time. It was in Shatila, Lebanon, where she facilitated "Peace in Exile", a creative workshop for young Syrian and Palestinian women and girls. She grew to love her students more than she could have expected, imagined, and perhaps even wished for. She was baffled by not only the women's bravery and unceasing strength but also their undiluted vision of the cards life has dealt them. Resilience, she recognized, comes at a great cost, a sacrifice too often overlooked. They became her thriving force to find any avenue to tell their story.

To fight for the rights of others with mindfulness and levelheadedness requires a realistic expectation for and understanding of the Self. Anrike was compelled to seek the truth of her heritage, confronting the experiences endured by the women of her bloodline through centuries of war, oppression, and occupation of Estonia. Trauma can be inherited across generations, epigenetically, adding complexity to the human drama. This implies that the experiences of our ancestors may influence how our genes express themselves. Covering an empty canvas with oil painting has been the method of unwrapping its impact on herself.

Anrike Piel's artwork has evolved into immortalizing the resilience of courageous women globally who boldly strive for their rightful place and refuse to be silenced. It is an exploration of the forces that shape identities, a thorough examination of her background, and a deliberate effort to confront trauma for healing.

Anrike turns to art as a potent communicator, not to engage in political debate about other people's humanity but to open hearts to empathy. Her art serves as a mirror reflecting the shared humanity demanding recognition, protection, and a righteous fury for justice, urging viewers to see themselves in the experiences of those too often relegated to the status of 'others.'

Hunger Strike, Oil on Canvas, 90x70 cm, 2023 © Anrike Piel

INTERVIEW

First of all, when and how did you start getting involved with art?

For as long as I can remember, it was storytelling fashion photography that I thought I would be doing forever. I lived in some of the most vibrant countries in the world for over a decade, with fierce passion, doing just that. But after volunteering at a refugee camp for the first time, I lost all interest in it. It was like a mid-life crisis that came too early, and I'm still adjusting. Yet it opened up so many new avenues for creation and brought meaning to my life that I had longed for.

Are you still following the same inspiration? And how did your work evolve over time?

Whenever I look at someone's work, I think about what they were feeling, thinking about, and experiencing at the time of creation. Now, putting my own work in chronological order, starting with fashion photography to the present moment, I recognize similar themes such as powerful femininity, courage, and vulnerability, yet I'd say there was more escapism in the form of looking for an alternate universe of peace. These days, inspiration comes from confronting reality and seeking answers.

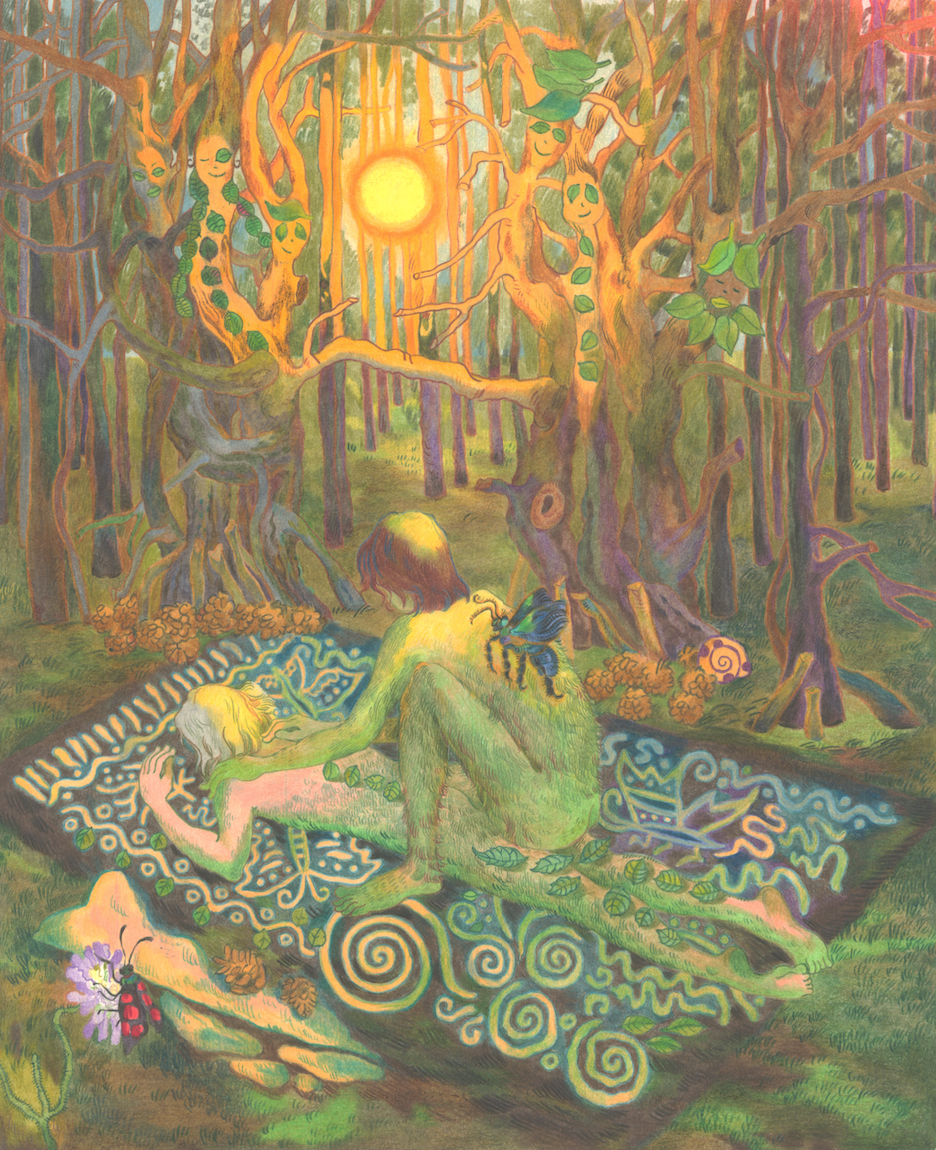

Judgement, oil on canvas, 150x120 cm, 2023 © Anrike Piel

Surrender, oil on canvas, 150x120 cm, 2023 © Anrike Piel

Let's talk about your work. You mention transitioning from fashion photography to oil painting as your chosen medium for self-expression. What inspired this shift, and how has it influenced the themes and messages conveyed in your artwork?

It truly was for the purpose of self-care that I began painting. After volunteering for the first time in Lebanon, Shatila camp, I was shattered. I was shocked by the silence of the Western world, the narrative created about refugees as if they are less deserving humans, and how the people around me normalized or ignored this incredible injustice. And I was confused - how did Estonians forget so fast that we were in the same situation just a few decades ago?

I couldn't carry on as before. I wanted my artwork to be a voice for the incredible people I've met who are in search of safety, for the oppressed, and for the people in the fight for justice. But that shift also came with major mental health challenges. To sustainably be there for others in traumatic situations without destroying oneself, a person needs to face their own demons and understand oneself thoroughly. I had to stop running away from the truths of my upbringing and experiences of womanhood.

As a person, I am a cheerful goofball for real, but on the canvas, I pour my excruciating vulnerability of the traumas I have had to endure or witness and investigate how the intergenerational trauma haunting my bloodline since the times of the Nazi invasion or the Soviet occupation affect me now.

You have a striking style with recognizable characteristics and colors. How did you choose the subject to paint?

The ideas for paintings always begin with an emotion. The subject is almost always myself, but that's because I exist in this body. The subject is a symbol, a human being who could exist anywhere, with no limiting borders.

Rose Murex, Polymer Clay, Seashell, 21x20 cm, 2022 © Anrike Piel

Where do you find inspiration for your work, and what is your creative process like?

I'm an artist at the core but a humanitarian first, if that makes any sense. My art gets inspiration from wherever my advocacy work takes me. Even at times when I'm completely burnt out, I just doodle or let the watercolor run on wet paper and create unintentional shapes.

I'm currently living in my home country, Estonia. We have these long, monochrome, dark winters here with almost no sunlight, so my process is much slower. I stare at a blank canvas for days and sometimes weeks. I'm much more in my head, and some concepts take so much effort to find the energy to mix the paint and hold a brush. The darkness makes me incredibly tired.

Living in Spain, I recognized the piercing blue tones of the sky in Dali's paintings. Or the cactus garden at Montjuic in Miranda Makaroff's vibrant feed. There is no one like Carlotta Guerrero, yet she perfectly captures the essence of the bold feminine energy of Spanish women, which encourages others to channel that femininity in themselves. I also took some of my favorite fashion photos in Spain and painted some of my favorite paintings. The sun just hits differently.

After working amidst the national emergency, assisting the tens of thousands of Ukrainian refugees who came to Estonia, I escaped to the Canary Islands to be in peace and quiet. I think I photographed every volcanic rock there as I found so many different images, movements, and bodies in them. Inspiration just flows in my veins when I'm in Spain… It's a different experience from any other place I've lived.

What do you hope that the public takes away from your work?

Disgusting vulnerability, empathy, compassion. While people's environments and conditions might differ, emotional experiences and basic needs are universal.

Peace in Exile - Estervan, Ritsona, Greece, photograph, 2018 © Anrike Piel

Peace in Exile - Nada, Ritsona, Greece, photograph, 2018 © Anrike Piel

"Peace in Exile" is a project you founded in 2017 to provide a creative sanctuary for young refugee women and girls. How has this initiative impacted both the participants and your own artistic journey? Can you share a specific moment or experience from the project that has left a lasting impression on you?

We turned our classrooms into makeshift paradises - either designer clothes hanging everywhere (which were donated for the first workshop) or tables covering materials to upcycle second-hand clothing and all sorts of supplies that can be used for imaginative makeup looks.

Once, a 15-year-old participant got ready for a photo shoot. Without hearing myself, I was in my fashion photographer role, commenting after every shot, "beautiful!", ‘’gorgeous!’’. Suddenly, I noticed tears falling down her cheeks, but she remained in front of the camera and kept posing. She was so confident. We didn't speak the same language but as we finished the shoot we hugged for minutes. Later, I asked the assisting teacher, a Syrian artist, Fida Alwaer, why she thought the girl teared up, and she pointed out the affirmations I kept giving her that perhaps made her feel she was seen, she was valued, she mattered.

An editor of a well-established fashion magazine criticized me for creating this project: "How does this help anyone?". It was a safe environment where the participants got to experience normality. They got to be just girls. Excitement filled the room every time they entered it. So that's all. It didn't fix any problems, but in situations where hope is hard to hold onto, it's crucial for survival, and entering a fantasy world can help to affirm that this is a circumstance, not defining who they are and their worth. Without imagination, there is no hope, no chance to envision a better future, no place to go, and no goal to reach.

Even as years pass, I break down every time I have to write about that experience. The girls changed me for the better; they gave my life meaning, and they have kept pieces of my heart that will never be whole again. I hope they are okay. They are so deserving of everything beautiful the world has to offer. However, the reality is that the international community has left countries that are already struggling with a burden of about 2 million refugees, so the tensions are high. Many refugees are waiting for UNHCR's promises of relocation for years and years while living in tough conditions or having no option but to return to their wartorn home country…

What are you working on now, and what are your plans for the future in terms of new projects?

Just before COVID, I began filming a documentary film in Estonia that is now called Beyond Exile. It's about a diverse group of women in Estonia confronting their complex cultural identities against the backdrop of a nation emerging from its insecure past. Through intimate stories of resilience, the film uncovers the lasting impact of war, migration, and systemic racism, shaping a narrative that analyzes the impact these experiences have on one's identity - how their experiences have influenced their world views and decisions, both individually and national. Covid halted the process of post-production, but I'm more motivated than ever to finish the film as, unfortunately, the topic only gets more relevant.

Besides that, I spent 2023 creating my first collection of large-scale paintings and am now in the process of getting them shown. Obviously, Gaza is on my mind day and night. I have been busy organizing protests and such and battling with burnout, so everything else has fallen secondary.

Of love and war, polymer clay, seashell, 20x18 cm, 2021 © Anrike Piel

Do you have any upcoming shows or collaborations you are looking forward to?

Before October, there were so many plans that today feel like a century ago. Since my advocacy work, a few opportunities have just fallen out. I don't know if it's a coincidence or not. But I'm getting back on the horse, as they say.

Finally, where do you see yourself and your work in five years from now?

The five-year plan is currently a bit foggy. I unexpectedly quit fashion photography in the blink of an eye, while I had previously drawn out my ten-year plans for it. Life can be so unpredictable. I'm now taking it more like improv theatre, going with the flow. I know for sure that in five years, my paintings and I will have a permanent home somewhere in Spain, and my art will have the opportunity to be seen by more eyes, being a voice for the people unheard. But currently, I want to finish the documentary, and I have no idea where this will take me. I want to get my artwork out there again. Additionally, I have applied to volunteer in women's empowerment centers in Uganda and/or Ghana. Once I get a confirmation, I will build the rest of the plans around it.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.