10 Questions with Jacqueline Heer

“To be an artist in the largest sense is to be fully awake to the totality of life as we encounter it, porous to it and absorbent of it, moved by it to translate those inner quickenings into what we make”.

Jacqueline Heer is a conceptual artist who works with diverse techniques, media, and materials to construct immersive mental and physical spaces. Her practice focuses on the relationship between perception and reality, challenging conventional boundaries and inviting viewers to engage in deeper contemplation of their surroundings and their role within them. In recent years she has been integrating technology (as it becomes available) with self made and found objects, painting and performances to create environments that aim to expand the mind, provoking new ways of seeing, thinking, and interacting with the world.

Her work has been exhibited and collected internationally, with museum shows at the North Carolina Museum of Art, SECCA (Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art), and The Light Factory Museum of Photography. Notable solo exhibitions include Stockeregg Gallery Zürich (with Hiroshi Sugimoto), Art Basel Miami, Bill Lowe Gallery in Atlanta, GA and Santa Monica, CA. She has presented multimedia installations and performances at venues such as The Knight Gallery in Charlotte, NC; The Light Factory; The Moving Poets Berlin; Queens College in New York; TNT Gallery in Shenzhen, China; Kühlhaus Berlin; and Karl Oscar Galerie Berlin.

In addition to her artistic practice, Jacqueline Heer is the founder and current operator of ping-pong between ART and Knowledge, a project space and residency program in Berlin. She also founded and operated The Limbo, an alternative gallery and the Eight Street Art Collective in Charlotte, NC. Heer has led various international public actions and held a guest professorship at HISK in Antwerp.

Jacqueline Heer has been travelling extensively, including Central and South America, Russia, Japan, and China, and now lives and works in Berlin, Germany, and North Carolina, USA. Her interest is the complex dynamics of global systems humanity has created, and the ways in which they interact—or fail to interact.

Jacqueline Heer - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

The cat is out of the bag … or perhaps it remains in Schrödinger’s box. AI is here to stay, introducing new uncertainties in how we see, think, act, and make ART.

Jacqueline Heer believes the essence of human creativity remains deeply relevant—shaped by our unique experiences, memories, and emotional nuances. AI can be a powerful tool for artists, but it is the artist’s imagination and unique life experience that has the ability to detect and give form to sensory insights that continue to define the true nature of ART.

Heer’s practice as an artist has always been propelled by a passionate curiosity about the “adjacent possible” and a desire to penetrate the membrane of the present, to find that special angle to gaze beyond the layers of the obvious and discover new shades of the possible.

Collaboration with computational methods is no conflict for Heer; in fact, she invites the challenge as it forces her to contemplate our very existence and the path humanity is taking. At the same time, Heer is aware that her experience must be focused inward, connecting it to that strange place where things are beginning to make sense. Working from that point has been the most satisfying for her.

She best describes herself as a “bipod” because her viewpoint straddles two worlds—science and art—providing a kind of stereo vision. When reason fails between these two poles, she has to let go and find the sweet spot, a flow, before the clash begins again. Her role, as she sees it, is to keep these channels open, to challenge the walls of our collective box—and perhaps set the cat free in the process.

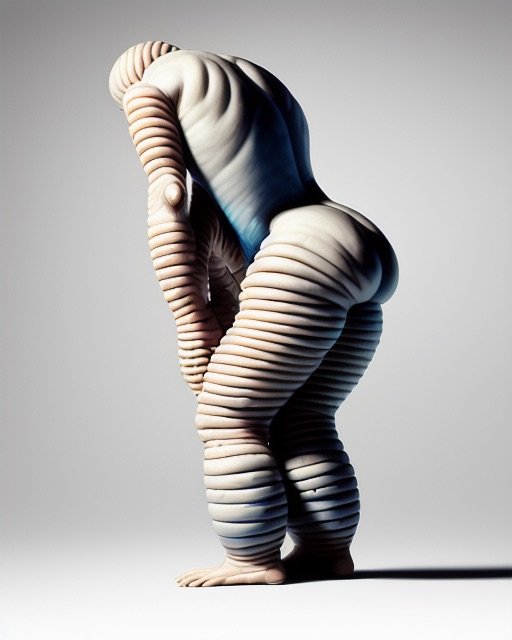

The Thinker, Digital Drawing, 2019 © Jacqueline Heer

INTERVIEW

First of all, introduce yourself to our readers. How did your journey as an artist begin, and what led you to this path?

When asked to introduce myself, I like to reach for a globe, as this is where I feel most at home. I left Switzerland as a young woman, breaking off both formal scientific studies and formal art studies—I headed not westward, as most did at the time, but east. It was the 1970s, the Iron Curtain was tight, and Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union were still an “exotic” destination. This set off nine months of moving further east—through shifting cultures, including Japan—before an extended road trip through North America eventually landed me in New York City, a destination that became an origin. Once established, I simply forgot to go back home. For most of the next three decades, I commuted between New York and North Carolina in the American South, where I raised a family, founded an alternative art center, and developed my practice as an artist that stretched from performances to deeply personal installations and large-scale public works. My path has never been a straight line—it’s been more like an orbit, shaped by departures, returns, and reinventions, all informed by a restless curiosity about life on this globe. By the late ’90s, I found myself “drifting” to Berlin, where I still maintain a strong presence today.

IMG_9547, Digital Painting, 2018 © Jacqueline Heer

How did you develop into the artist you are today? What training or experiences helped you along the way?

Picture this: a house in a small Swiss town, a fenced garden, geraniums spilling from windowsills, life unfolding in the quiet rhythm of the bucolic. My childhood there was one between two worlds—on one side, my grandmother, a deeply spiritual, wildly talented philosophical artist; on the other, my older brother, a scientist in spirit, anchored in the stark clarity of logic and pragmatism. I absorbed them both, their opposing currents still running through my veins and fundamentally informing the way I think, the way I see the world and the kind of Art I produce. I have become the point of tension—or maybe the synthesis—of these diverging forces. It shaped me then, and it still shapes me now — it's the basis from which I feel, think and work, my mind oscillating between the rational and the ephemeral, the measured and the ineffable and forever translating one into the other.

Your practice explores the relationship between perception and reality. What first drew you to this theme, and how has your approach evolved over time?

I understand "Reality" as a human construct—a local perspective shaped from the vantage point of Earth, built upon the knowledge and tools humanity has developed. It is always relative; there is no absolute. Human perception of this reality is shaped by cultural, religious, and political systems, making truth itself fluid. In my practice, I seek these boundaries, the spaces in between — exploring the relativity of truth while recognizing that we exist in a three-dimensional world, with any additional dimensions remaining abstract, perceptible only through the lens of mathematics and physics. This perspective informs my work on every level; it is the very foundation from which I operate. My scepticism of anything absolute drives me to question, reassemble, and re-code forms, always seeking to uncover the constructed nature of perception itself. Over time, my approach has evolved through the integration of new technologies and my continued interest in scientific progress, supporting me to push my artistic process toward increasingly dense and layered expressions.

Untitled No. 2, From the series “Silicon Daze”, Archival Print, 120 x 120 cm, 2024 © Jacqueline Heer

Untitled No. 9, From the series “Silicon Daze”, Archival Print, 120 x 120 cm, 2024 © Jacqueline Heer

You work across diverse media, from painting to performance and found objects. How do you determine which materials or techniques best suit a particular concept?

People familiar with my work have said I would have made a great stage set designer, and I understand why. I really like to respond to given locations, to particularly relevant, hidden issues, shaping my concepts in direct relation to them—this extends to the materials I use. Rather than starting with a fixed medium, I let the concept determine the form. More often than not, I work with found materials on-site, collect elements specifically relevant to the concept, or fabricate them myself. This approach keeps the work fluid, responsive, and deeply engaged with its environment. At the centre of my process is always the expressive impact I seek to create and the meaning I aim to convey—how materials, space, and viewer interact. My mediums include painting, fabricated objects, media, words, sound, or light, all assembled into a site-specific whole. I rarely see my works as isolated pieces; instead, I think of them as words in a sentence—interconnected fragments of a larger whole. This is why I often reassemble existing works, re-coding them with new meanings. The forms they take might emerge as a poetic stylization of rational knowledge or perception's relativity, but I always aim to expand some boundaries of human imagination. The choice of medium is never incidental; it is integral to the work's language. Much like a stage set is more than a backdrop to a script, my materials create a space—both visual and conceptual—where meaning can unfold.

Technology plays an increasing role in your work. What excites you about integrating new technologies, and how do they shape the experiences you create for viewers?

One could claim that anytime we pick up a tool, we use a certain technology—whether it's a stick, a brush, a chisel, a saw, a camera, or soft- and hardware. These are all part of a continuum of tools, each shaping the way we work, think, perceive, and express. From this perspective, working with a broad spectrum of resources, including emerging technologies, appears to me as a natural evolutionary progression in artistic practice. Just as past innovations—from the invention of perspective in painting to the development of photography—have profoundly expanded artistic possibilities, contemporary digital tools offer new dimensions for engagement, interaction, and meaning-making.

I do not see technology as something we "arrive at" but rather as a constantly shifting field that reshapes our lives and continuouslyredefines our understanding of reality. Contrary to the notion that humanity simply adopts new tools, it is increasingly clear that technological innovations actively shape human perception, cognition, and even social structures. Our reality—or what we assume to be reality—is constantly modulated by these shifts. Sensing such hidden fault lines is precisely where the essence of art is situated. History overwhelmingly demonstrates that, when not dictated by market forces, art serves as a highly sensitive universe where such transformations are not only recorded but often anticipated.

In my work, integrating new technologies allows me to expand the sensory experiences I aim to create, frequently challenging conventional modes of engagement. I believe that digital and AI-driven media have the potential to further dissolve traditional boundaries between the viewer and the work, creating immersive environments where meaning is co-constructed rather than passively received. As media theorist Marshall McLuhan claims, technologies function as extensions of human perception, reshaping not only how we communicate but also how we construct meaning itself.

What excites me is not just the sheer profusion of new tools but the philosophical and perceptual questions they introduce.How do these evolving technologies alter our understanding of presence, materiality, and, of course, also of authorship? What does an artwork become when its form is non-static, fluid, or even autonomous? These are the inquiries that drive my work at this point—not as a celebration of technological novelty, but as an examination of how our fundamental experience of art and of reality itself is continuously being redefined.

Print Installation View © Jacqueline Heer

Your immersive environments invite deeper contemplation. What kind of reactions or interactions from viewers have been most meaningful to you?

In general, any reaction—so long as it is honest—holds meaning for me. I pay close attention to how viewers engage with my work because I consider art a form of communication, and its impact is ultimately its raison d’être. The audience is always present, even during the production process itself. I anticipate their presence, their movement, and theirinterpretations while diligently maintaining a clear distance from anything didactic or instructive—focusing instead on allowing the work to exist as a dynamic space of exchange.

Some of the most meaningful responses have been those that reveal a shift in perception—when viewers express a sense of discovery or an altered awareness of space, time, or materiality. For example, in my site-specific installations, where found objects, media, and light converge, I have observed how the layering of sensory stimuli can provoke moments of disorientation, curiosity, introspection, or even bewilderment. These responses echo certain phenomenological perspectives, such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty's notion that perception is not merely passive reception but an embodied interaction with the world—a concept that also resonates with Heideggerian thought. I am particularly interested in the tensions between the known and the unfamiliar, between what we assume to be reality and the spaces where that certainty dissolves. In past works, I have witnessed viewers physically adjust their stance, slow their movements, or engage in unexpected gestures—an indication that the work has momentarily disrupted habitual ways of seeing and being. In one installation, a visitor once remarked that they felt as though they had stepped into "a coded language they instinctively understood but couldn't quite articulate," which resonated deeply with my approach to creating environments that invite both recognition and ambiguity.

Ultimately, the most meaningful interactions are those where the work becomes a site of inquiry rather than resolution—where the audience is not merely a spectator but an active participant in the negotiation of meaning.

Your project space and residency program in Berlin bridges art and intellectual discourse. How does this initiative complement or influence your own artistic practice?

My project space, Ping-Pong Between Art and Knowledge, is, in many ways, a miniature incarnation of the warehouse on 8th Street in downtown Charlotte, North Carolina—a sprawling, freewheeling alternative art space I founded and ran from the '90s into the 2000s. But its role there was quite different. At the time, Charlotte had no pronounced subculture or alternative art scene, so part of the mission was simply to create an autonomous environment where experimentation could happen. Berlin, of course, had no need for me to bring this kind of cultural expansion! Here, I'm able to focus the project space and residency program more precisely on the intersections of art, science, and technology—areas I see as crucial to understanding the evolving role of art and artists in shaping the future.

At its core, Ping-Pong Between Art and Knowledge is a framework for exchanging a wide range of perspectives and ideas. It's a space for dialogue, not conclusions—a platform where concepts are tested, reconfigured, and reimagined. Thinkers such as John Lovelock, with the Gaia hypothesis, futurist Ray Kurzweil and artists like James Bridle and Trevor Paglen provide key reference points. Our network of participants and residents includes artists, scientists, and cultural practitioners of all kinds, exploring and reflecting on the role of art in human evolution, the impact of emerging technologies, and how these forces reshape perception and reality. And because Ping-Pong is a private initiative at this stage, we enjoy the freedom to unravel norms, even provoke uncertainties and most of all, to be blunt and rethink everything—my personal mantra!

At this point, we are also interested in forming partnerships with like-minded initiatives, particularly to exchange residents, to intensify the dialogue and expand the network.

Morphogenesis, Print Installation View © Jacqueline Heer

No. 48, From the series “Morphogenesis”, Archival Print, 120 x 160 cm, 2023 © Jacqueline Heer

Morphogenesis, Video Still, 2025 © Jacqueline Heer

Your work has been exhibited internationally. Have you noticed different interpretations or responses to your work depending on cultural or geographic context?

Oh, absolutely. Reactions to my work can vary wildly depending on where it's shown—sometimes in ways I expect, sometimes in ways that completely surprise me. Certain themes, especially those dealing with perception, reality, and technology, tend to resonate across cultures, but the way people engage with them can be quite different. For example, in parts of Europe, where there's a strong intellectual tradition of theory-based discourse in art, viewers often approach my work through a conceptual lens, analyzing its philosophical implications. In the U.S., I've noticed a more immediate, visceral response—people tend to engage with the experience first, then process the ideas. And in places like China, where I've exhibited as well, there's often a fascinating dialogue about tradition versus innovation, especially when my work incorporates new technologies. What I love is that no matter where the work is shown, people bring their ownframeworks, biases, and cultural reference points to it. That's part of what keeps it alive—it's never static, never tied to just one meaning. Instead, it keeps evolving in conversation with its surroundings and expands my range of perspectives.

How do you see the role of conceptual art evolving in a world that is increasingly shaped by digital experiences and rapid technological change?

Conceptual art operates independently of medium—its essence lies in the navigation of ideas, not the materials used to express them. Today's hyper-technical tools, from AI to immersive digital environments, are simply an extension ofartisticlanguage, no different in principle from a brush or chisel. What they offer is not a shift in conceptual grounding but an expansion of the terrain in which ideas exist.

In this expanded field, it appears that the hidden dimensions of our technological landscape have the capacity to become both material and subject. I think we're looking at a paradox of transparency—where data, images, and interactions are endlessly visible, yet their underlying structures remain impenetrable. Conceptual art moves along these latent spaces, tracing paths through neural networks and algorithmic logic, making the systems that shape perception visible. The question for me is not whether technology alters the conceptual nature of art but how conceptual art can reveal the unseen architectures that govern our digital reality and the effect they may have on our future.

Untitled, Layered Painting on Plexiglass, Acrylic Paint, Collage in Acrylic Box Frame, 100x100 cm, 2024 © Jacqueline Heer

And lastly, what are you currently working on, and what directions or ideas are you most excited to explore next?

Lately, I've felt an almost physical need to step away from the screen and work more tangibly—to build things, to see material take shape beneath my hands. After years of deep engagement with digital media, I sense not just my owncraving for physicality but a broader desire within the art world to return to something more grounded, something that exists beyond the ephemeral. While I have decades of experience working with physical materials, the challenge now is to translate today's increasingly immaterial, spatial, and non-physical human experience into matter. This has led me back to an approach I first explored in the early 2000s—working with transparent substrates. I'm now reaching back to these techniques by layering various painted foils and plates, even objects, to create a kind of three-dimensional "holographic space". This work is still very much in the experimental phase, but I'm excited to push it further and see how this physical layering can evoke the complex, layered nature of contemporary experience.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.