10 Questions with Sarah Buckius

Sarah Buckius (b. 1979 Urbana, IL) is an artist and educator living in Northern California. Her recent creative work involves “Intertwined HerStories” which are montaged videos situated at the cross-section of *-women -*- technology -*- lens-based media-* and that interweave her performances for the camera in which she reenacts the paid and unpaid labor of women from history alongside the enactment of her own labor as a mother, artist, educator from the perspective of a woman who also studied mechanical engineering and industrial design. Her creative work has been exhibited nationally and internationally.

Her recent individual work has been exhibited online at “the museum of americana”, Superpresent Magazine, SCOUT 2021 (Denmark, Germany), IncuArts Gallery, “the MASS” collection, and Pineapple Black Gallery (Middlesbrough, UK). Her recent collaborative work as part of The ManosBuckius Cooperative (The MBC) with Melanie Manos has been exhibited at the “Media City Film Festival” (2022 Ontario, Canada), Espacio Gallery (2021 London, UK), Switch 2020 (Nenagh, Ireland).

Other notable video screenings include The State of The Art: Accademia di Romania in Roma (Rome, Italy), InsideOut Step2: White Box Museum of Art (Beijing, China), SIMULTAN #6: Past Continuous, Future Perfect | (Timisoara, Romania), Visions in the Nunnery: Nunnery Gallery (London, UK), EXiS 2010 International Film & Video Festival (Seoul, Korea), Images Contre Nature 2011: P’Silo International Experimental Video Festival (Marseille, France), and AC Institute Rotating Video Project (New York, NY).

She was an Assistant Professor of Photography at Michigan State University from 2010-2011 and has worked as an adjunct instructor of digital art, photography, time-based media, and art appreciation at Augusta State University (2012), the University of Michigan (2007-2010), and Eastern Michigan University (2009-2010).

Sarah Buckius portrait

Hidden Mothers: Re-& Enactment of Emotional Labor | Project Description

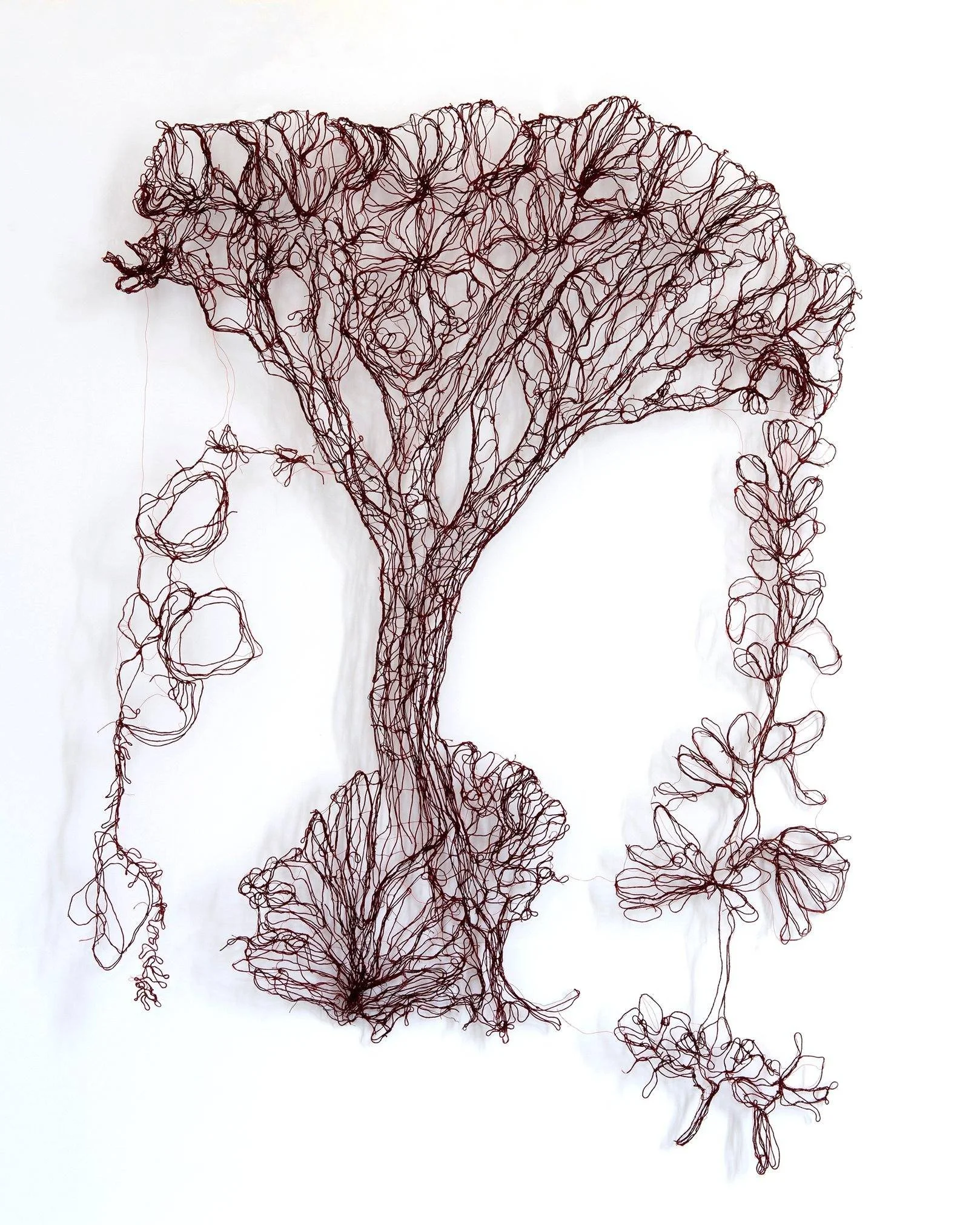

Mothers go to extraordinary lengths for their children. For “Hidden Mother Photography” in Victorian times, shutter speeds were sometimes up to 30 seconds long, so mothers would hide within the picture to hold their children still. Mothers revealed and concealed themselves in order to create a “permanent document” of their children’s “identities”. This emotional labor is considered “invisible labor” because it is unpaid, undervalued, and often goes unnoticed in our culture. Instead of concealing their identity, Buckius proposes that the emotional labor these mothers perform actually REVEALS much about their identity–their ingenuity, inventiveness, commitment, and emotional labor and strength. Buckius’ “moving portrait of emotional labor” pictures the process of photographic portraiture. She reenacts their labor, along with enacting her own, as she pays tribute to the unpaid “hidden” labor of mothers that is performed universally, continually, unfailingly, throughout the world, thus monumentalizing it as collective and “visible”.

Limited edition art collectors’ book

INTERVIEW

First of all, tell our readers a little bit about you. Who are you and how did you start experimenting with images?

I am an artist and educator whose recent work sits at the cross-section of gender, technology, lens-based media, the human body, and caregiving. My interest in technology likely stems from my bachelor's degree and work experience in mechanical engineering and my studies and work in industrial design. For my M.F.A. at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, I focused on what I call "performance for the camera" in which my lived body is the subject of identity-based work in photography and video. In addition, for the past 8.5 years, I have been the primary caregiver to my three young daughters and have been acutely aware of the relationship between the female body and reproduction due to childbearing, childbirth, caregiving, surgeries, and illness related to female reproductive organs.

What is your personal aim as an artist?

The goal of my current work is to make visible the often invisible unpaid and paid work of women, specifically as it relates to technology and caregiving. This project is part of a larger series of works that I call "Intertwined HerStories" that incorporate reenactment of other women's labor from the past and the enactment of my own labor in the present. Our experiences become enmeshed, and I can feel empathy for and connection to their labor. In this way, the personal becomes political, and the work creates an entangled relationship between past and present labor.

Hidden Mothers: Re-& Enactment of Emotional Labor (Still) © Sarah Buckius

Can you tell us about the process of creating your work? What aspect of your work do you pay particular attention to?

This work is about the process of caregiving labor, specifically that of mothers. Performance for the camera embodies this labor because I perform the actual labor I do every day, and the camera captures it, so the technology of lens-based media makes visible the invisible unpaid labor of mothers. I set up two cameras for this project, one still camera with a long-shutter speed and one video camera to capture the printed image from history as a frame for recording my present labor of "posing" for the photograph. This process images layers of time, past and present, and layers of work, mine and that of these other mothers.

You work with video and photography. What are the differences and similarities to you between those mediums? And how do you work with each of them?

My work is rooted in the process of living, embodied labor so, for me, video and photographs of my performance with long shutter speeds show this sense of time/work/movement. The still photographic images cement a moment that is part of a larger process and monumentalize it. By montaging the various videos of time together, I hope to make visible the labor of care that connects people (often mothers) across the world.

Visualizing multiple versions of different moments in time at the same time is possible through digital editing technology. The film editing technology allows my work to transcend reality and coordinate time in ways that are not possible in real life. Caregivers would benefit greatly from a reimagined social system involving care coordination. This film editing technology allows me to envision labor visibility in a way that reimagines the idealized caregiving of coordinated shared care.

Hidden Mothers: Re-& Enactment of Emotional Labor (Still) © Sarah Buckius

Tell us more about your Hidden Mothers project. How did you come up with this idea?

As a mother of three young daughters, I am constantly aware of the everyday shenanigans and emotional labor of caregiving work. I feel a deep connection to other caregivers through a sort of shared meta-common knowledge of this work's emotional and physical intricacies. For me, mothering has always been about the link between two bodies and my new role as 100% responsible for another human being, through mind and body. This role changed me forever. The world is a different place once I see it through the lens of someone who has complete responsibility for the life of another human. My body begets another body and is responsible for its life. I am responsible for another person living or dying, for another little person's being happy or angry, being alone or in a community, being intellectually stimulated or not, being healthy or not. Drinking water or not. Eating or not eating. Playing or not playing. Exercising or not exercising. Moving or not moving. A mother's body is her child's body.

Where do you draw inspiration from for your work? Do you have any specific references?

My work is inspired by my lived embodied experiences and the everyday encounters with people and the world around me, including technologies. Relevant lived experiences include my being the primary caregiver for my three young daughters, living in my female reproductive body as understood through medical technology, pregnancy, and childbirth complications, and lived illness and surgical procedures, the immensely creative imaginations of my children, and lastly the lens of a woman with experience in mechanical engineering and industrial design. In addition, I'm inspired by non-fiction written works, including Mothers and Daughters of Invention by Autumn Stanley, Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez, Mother of Invention by Katrine Marçal, Who Cooked Adam Smith's Dinner? by Katrine Marçal, and Mothers & Others by Sarah Bluffer Hrdy. Recently, I cannot stop thinking about the science-fiction novel The Employees by Olga Ravn.

What is your favorite experience as an artist so far?

In 2004, I went to China with the graduate students in my M.F.A. cohort from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. I attached a video camera to a bike that I borrowed from a college student I met and filmed the view from the bike basket as I rode around the city. I believe this project inspired my future work at the cross-section of identity, technology, and lens-based media. The footage has a feeling of my being completely out-of-place, which is definitely how I felt. At the same time, I felt a deep desire to connect to the people and the new place and sit with our differences and similarities. My experience of feeling foreign can lead to my new perspectives about myself and an understanding of the importance of tolerance and the value of difference in terms of identity. I guess it lead to my recent interest in drawing connections between people and ideas that seem at once very different. Even though I do not know the women in these photographs from history, I feel a connection to them by our shared experiences of being mothers. When I feel a sense of displacement/difference, I desire to connect to others and understand them. But also, I learn about my own identity by way of understanding differences.

Hidden Mothers: Re-& Enactment of Emotional Labor (Still) © Sarah Buckius

What do you think about the art community and market?

For artists, it can be imperative to find a niche within the larger art community. I am interested in creating connections between the ideas of other artists and creative thinkers/makers because this can help make a wide, seemingly divergent space feel smaller and more specific.

What is one lesson you learnt from this past year's experience? And how did it help you further develop your art?

The pandemic has furthered my interest in finding "entangled constellations of connections," meaningful linkages/connections between ideas and people, and people's work (especially that of women) that are seemingly unrelated no matter how unusual, hidden, tenuous, this connection may appear. Such links create webs of connection that link people together, metaphorically and literally. For example, walking by a stranger on the street and smiling with my eyes behind my mask can create a momentary linkage/connection that can have larger impact on our systems of people and ideas.

Hidden Mothers: Re-& Enactment of Emotional Labor (Still) © Sarah Buckius

And finally, what are you working on now, and what are your plans for the future? Anything exciting you can tell us about?

I am working on a series of animations and games that feature what I am calling technoloffspring, which are absurdist technological beings birthed from "IntertwinedHerStories" originating from the cross-section of gender, technology, lens-based-media, the human body, and caregiving. This project proposes a reimagining of what "technology" might mean in the context of an absurdist caregiving society. These technoloffspring originate from an "entangled constellation of connections" as subjects of care and caregivers themselves.

These films and games incorporate found and developed digital imagery that depicts threads related to women's invisible paid and unpaid labor. The amalgam of digitally altered video, performance, animation, 3d modeling, 3d design drawings, illustration, photography, sound, and processing code seeks to bring together the creative voices of women (past and present) like a sort of digital community of women's creative work, recode the technological landscape (that is designed mostly by and for men) as inclusive of female and non-gendered code, and propose new technologies originating from caregiving. Absurdist games and films bring visibility to this work in playful, unexpected ways and place value in creativity in an absurdist resistance against and proposal for reimagining an alternative to patriarchal, capitalist, production-based, essentialist, seemingly rational, seemingly useful, logical, optimization-driven, commercialized, deterministic systems.