10 Questions with Maryam Nazari

Maryam Nazari is a Tehran-born (Iran) multidisciplinary artist, performance designer, curator, and artistic consultant, now based in London. Her artistic practice spans performance art, sound design, video art, and installation, with a focus on the intersections of memory, identity, and cultural narrative. Maryam’s work is deeply informed by her Iranian heritage and the dualities of private and public life and explores the impact of socio-political tensions on personal experience and artistic expression.

After completing her Master’s degree in Performance Design and Practice at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London, Maryam expanded her artistic career across multiple disciplines. In addition to her creative work, she has curated exhibitions, such as the International Women’s Day exhibition in collaboration with the French Embassy in Iran, and served as an artistic consultant on international projects, including her work in a collaborative project of the Oscar winner composer Amir Konjani with the London Symphony Orchestra. Her curatorial practice blends her multidisciplinary sensibility with a deep engagement in cultural narratives and innovative approaches to presentation.

Maryam’s work has been performed, exhibited, and screened in prestigious venues such as the Royal Albert Hall, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, and international galleries in the UK, France, Germany, China, Canada, and the USA. Currently pursuing a practice-based PhD at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, her research project, “Persian Carpet as a Site for Storytelling, Memory, and Artistic Interpretation,” explores the cultural and artistic significance of traditional Persian carpets.

Known for her innovative use of sound as both a narrative and structural element, Maryam creates immersive experiences that challenge the boundaries between audience and performer, inviting deeper engagement with themes of identity and cultural memory in a socio-political context.

Maryam Nazari - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Maryam Nazari’s work emerges from the complex dualities of Iranian life—where the public and private spheres are in constant negotiation. As an artist who grew up in Tehran and now resides in London, her multidisciplinary practice delves into the interplay of memory, identity, and cultural heritage, using the body, sound, and visual storytelling to explore these themes.

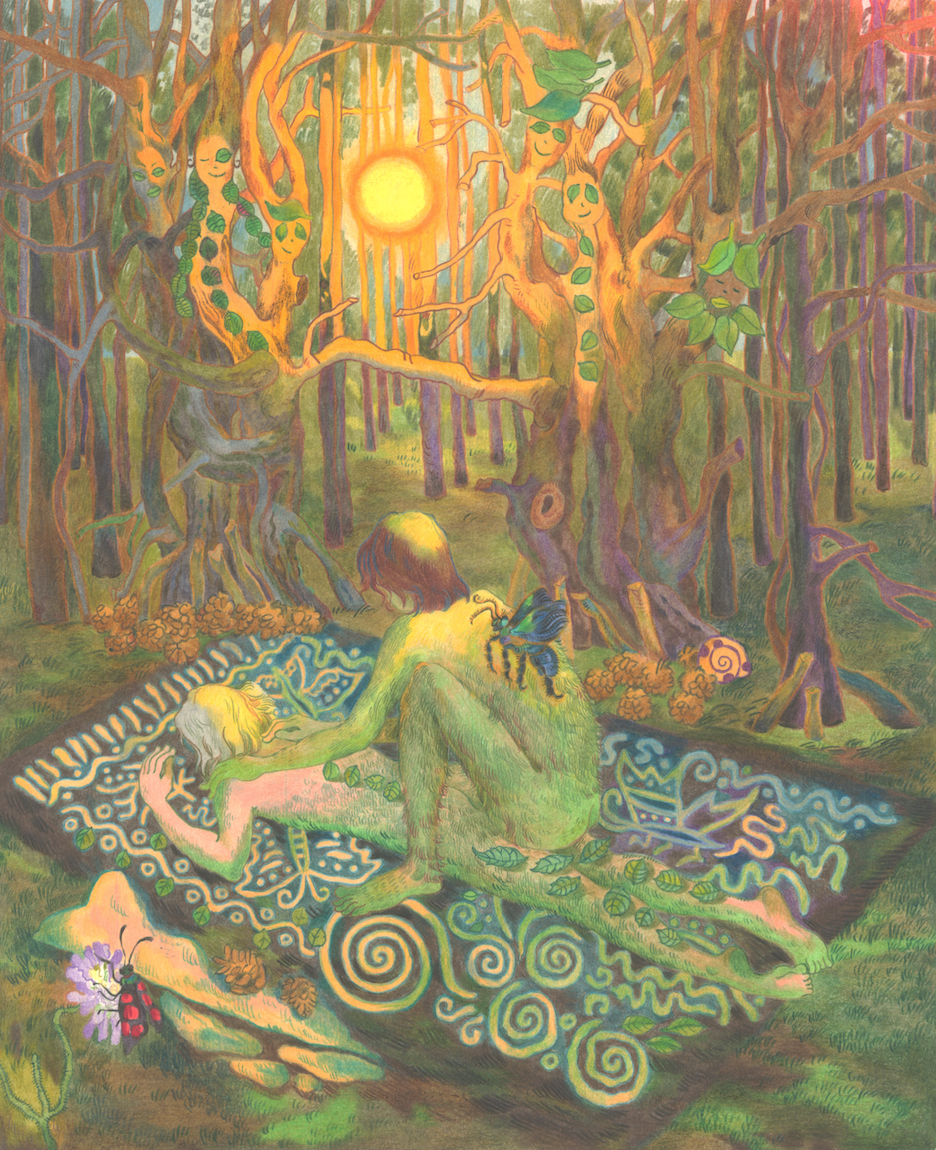

Her art is often centered around the Persian carpet, a recurring symbol in her work, which she interprets not merely as an object of decoration but as a living artifact that holds the stories, identities, and memories of generations. Through her ongoing PhD research, “Persian Carpet as a Site for Storytelling, Memory, and Artistic Interpretation,” Maryam investigates the dynamic role of this traditional craft as a participant in the formation of individual and collective narratives.

Maryam’s work is characterized by a deep engagement with sound, both as an artistic element and as a structuring force in her performances. Her unique approach, where sound acts as a director guiding the flow and timing of the performance, creates immersive environments that invite the audience to engage with the work on a sensory and emotional level. Performance pieces like ‘This Body Is All Bodies’ demonstrate this, where audience participation becomes a key element of the work, turning each performance into a collaborative and improvisational experience.

Her projects, such as ‘The Art of Slaughter’ series, often address sociological and political themes, yet they do so with subtlety and a refusal to engage in direct protest. Instead, she offers a reflective space for the audience to confront ideas about life, death, and identity. Through her work, Maryam strives to create layered narratives that encourage viewers to contemplate their own stories and the cultural contexts in which they are formed.

The Art of Slaughter, Still Image of a Video Art © Maryam Nazari

INTERVIEW

First of all, tell us a bit about your background and artistic career. When did you first approach art, and what helped you become the artist you are today?

My artistic journey began at the age of eight, when I first studied music. I was drawn to the Tombak, a traditional Persian goblet drum, which forms the rhythmic foundation of Persian music. Soon after, my passion for music expanded, and I took up the cello and Tar, an Iranian plucked string instrument, delving deeper into the world of sound and cultural expression. I pursued a Bachelor's degree in music, specializing in the Tar, but it was during the final project of my degree that I encountered a significant shift in my creative trajectory. Instead of focusing solely on the instrument, I developed and performed a performance art piece at a festival in an art gallery, marking my first foray into the broader world of performance art.

After this experience, I briefly began a Master's in Music, but the allure of creating across multiple disciplines led me in another direction. I realized I wanted to explore beyond the traditional boundaries of music and work within various artistic mediums. This realization prompted me to move to London, where I completed a Master's in Performance Design and Practice at Central Saint Martins. During this period, I embraced various roles, from performer and performance designer to sound designer, stage manager, curator, and artistic consultant (including a collaborative project between the Oscar-winner composer Amir Konjani and the London Symphony Orchestra). I also experimented with diverse art forms such as video performance, photography, video art, live performance, and sound design. These experiences enabled me to establish myself as a multidisciplinary artist—a path that I had been seeking all along. My work has since been presented, performed, and screened internationally in countries such as Iran, the UK, Germany, China, France, Canada, and the USA, among others.

Currently, I am pursuing a PhD at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. My research project, "Persian Carpet as a Site for Storytelling, Memory, and Artistic Interpretation: A Practice-Research Investigation", explores the Persian carpet as a rich, symbolic medium for artistic expression. This research deepens my inquiry into how traditional forms can intersect with contemporary practice, storytelling, and memory, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of my work.

Carpet as country, Photography series, 120x90 cm, 2023 © Maryam Nazari

Can you tell us about the journey from your early life in Tehran to your current base in London? How have these distinct cultural environments influenced your artistic development?

I was born and raised in Tehran, a city marked by its rich cultural heritage but also by the socio-political complexities following the 1979 Revolution and the eight-year Iran-Iraq war. These events deeply impacted my worldview and creative thinking. Growing up, I witnessed the stark contrasts between private and public life—how people navigated a double existence, adhering to government restrictions in public while cultivating personal freedom in the privacy of their homes. This dichotomy has been a central theme in my work, reflecting a perpetual tension between inner truth and external constraints.

Iran's environment demanded resilience and adaptability. As a child, I quickly learned to navigate conflicting messages—at school, I was taught religious and political dogma, while at home, my family encouraged independent thought. Thisshaped my understanding of identity, memory, and social norms, all of which now play a critical role in my artistic exploration. I often reflect on the question of freedom, not only as a political concept but as an inner struggle, and how performance art became an essential tool for Iranian artists to express themselves in a society where many forms of expression are restricted. Performance art, in particular, allows for a direct, unfiltered engagement with audiences, often circumventing censorship, which is why it thrives in Iran as a medium of protest and social commentary.

When I moved to London, I was suddenly in an environment where freedom of expression was not only protected butencouraged. The contrast was striking and liberating, yet it also introduced a different kind of challenge. In Tehran, the restrictions on artistic expression created a kind of urgency and depth in my work; in London, the artistic freedom offered me an expanded landscape to explore and experiment without fear of repercussions. However, the paradox is that this newfound freedom also required me to find new ways of challenging myself creatively. It's easy to become complacent when the external pressures of censorship are lifted, so I had to delve deeper into the nuances of my personal experiences, cultural memories, and the themes of displacement and belonging.

These two environments—Tehran, a place of complexity and constraint, and London, a hub of diversity and openness—have both been crucial to my artistic development. My work has always sought to bridge these worlds, using the language of performance art, video art, and sound design to explore the fluidity of identity and the layers of memory. Living in London has provided me with the space to reflect on the experiences of my early life in Tehran while my work continues to be shaped by the lasting impact of my homeland's political and cultural context.

As a result, my artistic practice often oscillates between these two poles: the personal versus the political, the private versus the public, and the traditional versus the contemporary. As I mentioned earlier, my work has been presented, performed, and screened in various countries, including Iran, the UK, Germany, China, France, Canada, and the USA, which has allowed me to engage with different audiences and see how universal themes like memory, identity, and resilience resonate across cultures.

Your work involves "Persian Carpets as Sites for Storytelling, Memory, and Artistic Interaction," as mentioned in your statement. Why did you choose these elements and how do you use them to convey your message?

The Persian carpet is more than an object of decoration; it is a living, breathing artifact that holds layers of memory, identity, and cultural narrative. I chose Persian carpets as the central element of my work because of their intrinsic connection to my upbringing and their broader significance in Iranian culture. As a child in Iran, I grew up surrounded by these vibrant carpets, and they became a silent yet constant witness to my everyday life, embodying the warmth, heritage, and complexity of my environment. These carpets are not merely static objects but dynamic participants in our lives, deeply interwoven with the stories of those who create, use, and cherish them.

My practice seeks to explore Persian carpets as more than images or ornamental objects; they are vibrant matter, as philosopher Jane Bennett would put it, with "thing power"—a force that actively shapes and interacts with the lives around them. Persian carpets have been a cultural canvas for centuries, where artisans weave intricate patterns that holdpersonal, familial, and national histories. They serve as a powerful metaphor for storytelling and memory, carrying generations of cultural knowledge through their motifs and designs. Each thread, each knot, becomes a narrative, a fragment of lived experience.

In my current project, "Persian Carpet as a Site for Storytelling, Memory, and Artistic Interaction," I aim to reimagine these carpets as spaces for both personal and collective storytelling. My work bridges traditional Iranian craftsmanship with contemporary multimedia experiments, allowing the carpets to become platforms for artistic interpretation. By engaging with their tactile and visual qualities, I evoke sensory memories of my childhood and the collective memory of Iranian culture. For instance, I work with video art, performance, and installations to reconstruct the sensory experience of these carpets, transforming them from decorative objects into active participants in artistic dialogue.

In a deeper sense, my work positions the Persian carpet as a relational object—an idea inspired by theorists like Jane Rendell and Nicolas Bourriaud—where the carpet invites interaction and engagement, not just visual admiration. Whether it is through the act of weaving or the careful process of unraveling in my video art, I use the carpet to explore themes of memory, identity, and the passage of time. Each interaction with the carpet mirrors our engagement with our own histories as we thread together moments of the past while simultaneously disentangling them to create new meanings. This tactile, relational interaction with the Persian carpet allows for an artistic exploration of how memory is not fixed but constantly woven and unwoven, much like the carpets themselves.

By employing these rich, multilayered elements, my work challenges the perception of Persian carpets as static cultural artifacts and repositions them as active sites for narrative, memory, and identity, allowing them to engage with contemporary artistic discourse while still honoring their cultural roots.

You also describe your art as emerging from the dualities of private and public life in Iran. How do you navigate and express these complexities in your multidisciplinary projects?

The dualities of private and public life in Iran have deeply influenced my artistic journey, shaping my understanding of identity, expression, and resistance. Growing up in a society where public life is governed by strict socio-political and religious rules, while private life often serves as a sanctuary for individual freedom and self-expression, has instilled in me a profound awareness of these tensions. This dynamic between the internal and external worlds is something I continually explore in my multidisciplinary projects, where I attempt to bridge these two realms through artistic expression.

In Iran, public life requires a careful negotiation of what is visible, permissible, and accepted, while the private sphere becomes a space where personal, familial, and cultural truths can be explored more freely. My work reflects these dualities, particularly through the medium of performance art and the exploration of objects like the Persian carpet, which itself embodies layers of meaning tied to both public display and private memory. The Persian carpet, often found in both grand public spaces and intimate family homes, serves as a metaphor in my work for this constant negotiation between the outward and inward aspects of Iranian life. In my projects, carpets act as sites where personal stories and collective cultural narratives intersect, much like how individuals in Iran navigate these two distinct realms.

Through performance and video art, I explore the tension between what is seen and unseen, what is said and unsaid. For instance, in my video work, where I weave and unravel carpets, I engage with the act of creating and dismantling—an expression of the complex layers of identity that are constructed in private and often hidden in public. The act of weaving becomes a metaphor for constructing a socially acceptable identity, while unraveling symbolizes the process of revealing private truths and personal narratives that resist external conformity. This duality is at the heart of my practice: the constant weaving together of public presentation and private existence.

My work also reflects this tension through sound design and performance. The use of the human body in performance allows me to juxtapose vulnerability and resistance, silence and speech—mirroring the ways in which individuals in Iran, especially women, navigate the expectations placed upon them in public life while holding on to their personal truths in private spaces. The act of performing, of occupying space with my body, becomes a way to reclaim agency and speak to the hidden layers of experience that are often censored or suppressed in the public sphere.

In navigating these complexities, I lean into the power of multidisciplinary art forms, using video, performance, sound, and installation to create immersive experiences that invite the audience into this world of dualities. Each medium I work with allows me to express different facets of these tensions: video captures the intimate act of weaving and unraveling, performance engages with the body as a site of public and private negotiation, and sound immerses the audience in the sensory experiences that are often associated with memory and personal identity.

Ultimately, my art seeks to give form to these dualities, creating a dialogue between the visible and the hidden, the personal and the political. It is in this space of tension—between what is allowed and what is repressed—that my work emerges, continually negotiating the line between expression and constraint, tradition and innovation.

Your art is very layered in messages and often touches on social and political issues. How do you handle these topics, and what do you hope people take away from your work?

In my work, I aim to explore the complexities of life, especially those that arise from social and political realities. However, I am not interested in direct protest or confrontation through my art. Instead, I approach these themes with subtlety, inviting the audience to engage with them in a reflective and personal way. My goal is to highlight truths that exist in the spaces between public and private life, often influenced by the socio-political landscape of my upbringing in Iran. I focus on conveying these issues from my perspective, not to provoke but to encourage contemplation. For example, in The Art of Slaughter series, I juxtapose the visceral act of slaughter with deeper meditations on life, identity, and human existence. I hope viewers leave with questions rather than answers, allowing them to interpret the layered meanings of the work based on their own experiences and reflections.

As a consultant and curator, how do you mix your artistic ideas with the projects you work on with others?

In my role as a consultant and curator, I blend my artistic sensibilities with a collaborative approach. I see curation as a form of storytelling, much like my own artwork, where each project contributes to a larger narrative. When working with others, whether it's for an exhibition or a performance, I try to infuse the project with the same attention to sound, space, and identity that defines my own practice. In Iran, for International Women's Day, we worked with ten female artists based in France, each with a different style. We had to consider their opinions on how their works should be presented,while also integrating our own curatorial vision and working within the gallery's restrictions. Balancing all these aspects was challenging, but the experience was highly rewarding. As a curator, I'm proud of what we accomplished, especially in creating a hybrid physical/digital exhibition as we began to emerge from the Covid era. The challenge and beauty of these collaborations lie in finding a balance between my vision and the collective goals of the project.

Rondo...Rondo...Rondo..., Performance, Kingscross Platform Theatre, London, 2017 © Maryam Nazari

You have collaborated with notable figures such as Amir Konjani and the London Symphony Orchestra throughout your career. Can you share a particularly memorable experience from these collaborations?

One of my most memorable experiences was working on a project with Amir Konjani and the London Symphony Orchestra, which was part of the Sound Unbound festival and supported by Jerwood Arts. It was a significant moment where sound, space, and performance truly merged. I remember the day before the performance when we were preparing the installation and bringing the design of the scaffolding structure to life. At the same time, we had to rehearse with the musicians and performers, which made coordinating everything a big challenge for us. However, we managed to pull it off successfully, and the performance turned out wonderfully. The collaboration taught me that working with other artists, particularly those from different disciplines, can expand the language of your own practice in unexpected and powerful ways.

You have also shown your art in places like the Royal Albert Hall and the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Arts. How do different audiences react to your work, and do you change your art for different places?

The way audiences react to my work greatly depends on the cultural and social context in which it is presented. In Iran, for instance, there is often a deep connection with the cultural symbols and narratives that I incorporate, such as themes of memory, identity, and the Persian carpet. Audiences in Tehran tend to approach my work with a nuanced understanding of these elements, engaging with them on a personal and collective level. On the other hand, in venues like the Royal Albert Hall or in the UK and the US, the response often leans toward the universal themes I explore—such as time, the body, and philosophical underpinnings—which resonate across different cultural contexts.

While I don't change the core message or structure of my work depending on the venue, I do adapt the presentation to suit the space and audience engagement. For example, at the Royal Albert Hall, the grandeur of the venue called for a more expansive, large-scale presentation, while at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Arts, I focused more on the intimacy and subtleties of cultural dialogue, which better suited the setting.

A good example of how different audiences engage with my work is my performance art piece, This Body Is All Bodies, which relies heavily on audience participation. I performed it first at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art and then three more times in London. The piece is sociological in nature, exploring the boundaries between the performer and the audience, and how those boundaries shift based on cultural contexts. In Tehran, the audience felt brave enough to actively engage in the performance, becoming part of the piece in a way that reflected their connection to the political undertones. However, in some of the London performances, the interaction wasn't as strong, partly because the audience was more hesitant to participate. This unpredictability made This Body Is All Bodies feel like an improvisational piece at times, where the performance evolved based on how the audience reacted in the moment.

So, while I don't alter the essence of my work for different locations, I am very mindful of how the space, the audience, and the cultural context shape the experience of the performance.

Patient Zero, Photo of an installation, 100x80 cm, 2020 © Maryam Nazari

Patient Zero, Photography, 100x85 cm, 2020 © Maryam Nazari

Looking forward, what are some of the themes or projects you are excited to explore next in your artistic journey? How do you envision the evolution of your multidisciplinary approach?

I am particularly excited to continue exploring the intersections of memory, sound, and physical space. One of the themes I am keen to delve into further is the idea of displacement and how physical objects, like Persian carpets, can act as anchors of cultural identity amidst shifting landscapes. I also plan to expand on my work with acoustic scenography, where sound functions as more than a backdrop—it becomes a central narrative force. My goal is to push the boundaries of how we experience art through the senses, blending sound, performance, and visual art into immersive environments that challenge traditional perceptions of art-making. I envision my multidisciplinary approach continuing to evolve, especially with new technologies and collaborations that offer fresh ways to interact with audiences.

And lastly, where do you see yourself and your work in five years from now?

In five years, I see my work becoming more immersive and large-scale, incorporating even more elements of sound design, performance, and installation to create fully realized environments. I aim to have my work exhibited in both experimental art spaces and major museums around the world, engaging diverse audiences in dialogue around themes of memory, identity, and the body. Additionally, I would like to continue curating and consulting, helping to shape interdisciplinary projects that bring together artists from different fields to explore new artistic languages. Ultimately, I hope my work will continue to resonate both locally and internationally, contributing to conversations about culture, art, and human experience.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.