10 Questions with Robin Dru Germany

Robin Dru Germany, BA (Philosophy-Tulane), MFA (Photography-University of North Texas), is a Professor in Photography at Texas Tech University in Lubbock Texas. Her research investigates the tenuous border between the human and the natural worlds, looking simultaneously at the capitalist-driven human world and the undisclosed activity of nature with emphasis on the undefined area between the two. Through the use of metaphor and storytelling, her images point to the asynchrony between these two environments while investigating the space that is neither human nor non-human. She resists the binaries of popular thinking about the climate crisis and asserts that the only path to change is through radical empathy and blurring of the line that separates our bodies from the environment in which we live and draws our life forces.

Germany has exhibited her photographs at the Fort Wayne Art Museum, the Center for Photography at Woodstock, the Manifest Gallery in Cincinnati, at the New York Hall of Science; in Arezzo Italy, at the Fotografia Festival; the Art Museum of South Texas in Corpus Christie, Texas; and in galleries and museums around the country. Germany has received numerous Texas Tech University research grants, and her photographs can be seen in the Collections of the Center for Photography Woodstock, the Texas Tech Museum of Art, The Boise Art Museum, and the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona, as well as numerous private collections. Most recently, she was awarded a one-month artist’s residency at the Bloedel Reserve in Bainbridge, WA. One of her photographs was included in the Contemporary Artists section of the newest edition of the seminal Photography textbook edited by Jim Stone and Barbara London, and her work will be in an upcoming exhibition at the Mulhouse Photo Biennial in Mulhouse, France.

Robin Dru Germany - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

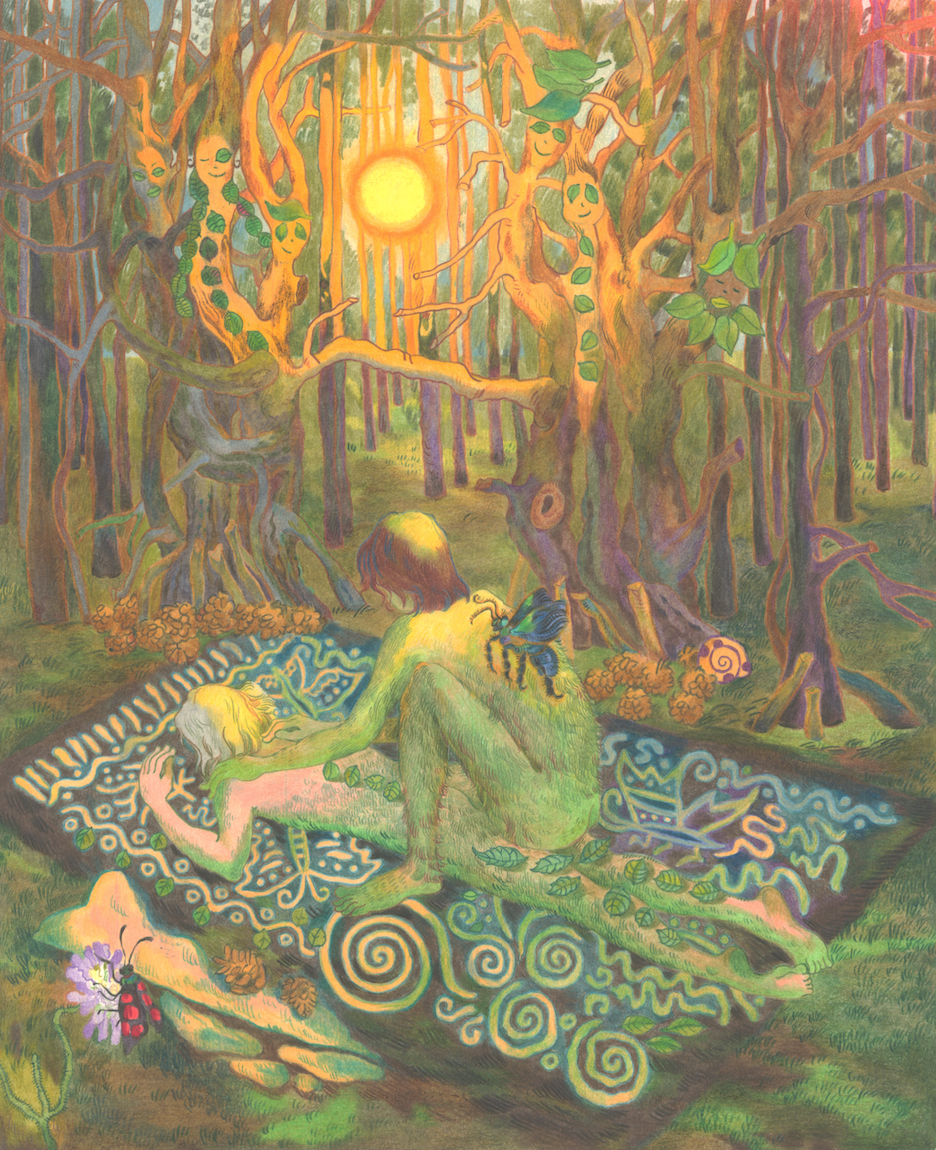

“Robert MacFarlane comments in his book Underland: “Nature seems better understood in fungal terms…as an assemblage of entanglements of which we are messily a part.” Through photographs, collage, and experimentation, I seek to unwind some small aspects of our serpentine relationship with nature, employing the mushroom as my guiding metaphor. With its current renaissance, the mushroom has found its way into our movies, books, medicines, fashions, and building materials. Mushrooms are both frightening (in fact, they can kill you) and beneficial (Lion’s Mane is thought to support brain health). They are part of our everyday lives in abstract ways, as tee shirt designs and household decorations, but their actual existence remains a mysterious or unknown concept. It is unsettling how quickly they appear after a rain or how they grow in circles around a tree. I am particularly focused on envisioning mushrooms as quietly, stealthily entering our lives as replacements or substitutes. I see them as intertwined with human bodies, using their hyphae to support our circulatory systems. Their structures branch and stretch much like our veins and capillaries. In my photographs, they silently crowd out the plastic, artificial versions of themselves and steadily insinuate themselves into our dreams and our reflections.”

— Robin Dru Germany

Elbow, pigment ink on paper, 20x27 in, 2024 © Robin Dru Germany

INTERVIEW

Please introduce yourself to our readers. Who are you? How did you become interested in art and photography, and what do you do today?

I am Robin Dru Germany, a photography professor at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas. I am originally from Texas and learned about photography from my parents. My mother was a journalist, and my father an engineer, but they both loved to take photographs with an Exacta 35mm camera. They set up a darkroom in a bathroom in my childhood home and taught me how to develop film and print negatives. My mother was always interested in art, and when I was very young, we would take my sister to the museum in Houston for art lessons. While waiting for her lesson to end, we would wait in the galleries at the museum. The Claus Oldenburg Giant Soft Fan-Ghost Version (1967) sculpture fascinated me with its huge cord and plug, and I continue to love images of plug and wall outlets in photographs (you can ask my students!). It's summer in Texas, and I am out of school. I'm spending the summer at the beach on the Texas Gulf Coast and by a river in central Texas, so I am taking night photographs of the water in both places. Initially, it's a motivation to wander near the water at night, to experience the other sounds, smells, and sights of the evening. As I make these images, I wonder what impact a photograph can actually have and how a photograph can shift a person's viewpoint, and I am reminded of the development of science fiction. Before it was imagined by science fiction writers, the idea of the robot had no hold on our imaginations. Once science fiction established a vision of a robot and a narrative, the potential for an actual robot became possible. Maybe photographs can work in a similar manner to posit future possibilities or propose hidden potency of our current moment.

With a BA in Philosophy, how do philosophical concepts influence your approach to art-making and photography? How did you transition from Philosophy to Photography in the first place?

When I studied Philosophy as an undergraduate, I was especially intrigued by conversations about how we know and understand the world around us. I learned about both the Eastern and the Western views of the self and found myself confounded by the rigid Western approach of separating the human world from the natural world, and creating a hierarchy for living beings. Through my art, I have been looking for ways to examine the space, if there is one, between the body and the world outside the body, such as the air, the table, my friend, and the ground. Or maybe I'm more concerned with the permeability of the body, wondering if maybe there is no clear division between myself and the things and beings around me. Learning Photoshop led me to think more about the artificiality of boundaries between our bodies and the things that make up our environment. I was initially surprised that when trying to select a person from the background with the lasso tool, if the person's body cast a shadow, the software could not tell which was the person and which was the shadow. Consider that edges, lines, and borders are artificial constructs. The beach is a great example of a transitional, borderless place, which is sometimes land and sometimes water, depending on the tides. You cannot assert at any one time that the beach is a "human" place or an "aquatic" place. I began making photographs in high school, and I was curious about how far one could push the medium in telling a story. Could I convey aspects of the story that cannot be readily verbalized, like an atmosphere or feeling? When I studied philosophy, especially philosophers who were more literary, I wondered if I could express ideas that are between words by using photographs. In some ways, it feels like using negative space to identify a subject.

Handmirror, pigment ink on paper, 20x22 in, 2023 © Robin Dru Germany

Bunapi bouquet, Pigment ink on paper, 24x24 in, 2023 © Robin Dru Germany

Speaking of your work, can you take us through your artistic process when creating a new piece or series? What are the key steps and considerations?

Most new series emerge from a thread of literature, a news article, or a film. I work primarily in the studio and when I am between projects, I photograph whatever objects are around me. I tend to fill my mind with interesting information, and then I photograph intuitively. One of my intentions, when I made the transition from philosophy to photography was to try to create visual images that embodied the philosophical texts I was reading. I felt certain that one could convey more subtlety and nuance with visual imagery than one could with words. When I tried to plan and literally insert the philosophy into the photographs, I saw that the results were static and flat. The images were more ambiguous but far more interesting when I stopped thinking about philosophy while photographing and simply responded to the materials (with the philosophical concepts always floating around in my subconscious). The process becomes one of play, experimentation, and surprise. In my current mycological still lives, I was initially mesmerized by the remarkable mushrooms a young farmer in my town was growing. Their surprising and complex forms were exciting studio subjects, especially in light of the many recent accounts I had read about mushrooms playing important roles in fashion, medicine, as building materials, and in breaking down toxic waste. I read Sylvia Garcia Moreno's book Mexican Gothic and The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben. Some of my photographs look like they are from a gothic mystery, and others seek to imagine how our bodies might be part of the World Wood Web.

As you mention in your statement, you resist the "binaries of popular thinking about the climate crisis." Could you explain how your work challenges these binaries and promotes a more nuanced understanding of environmental issues?

Binaries emerge from black-and-white thinking. But as I read more about plants, mushrooms, scientific categories, and how current research is challenging them, I am aware that the divisions we make between ourselves and others are artificial and unproductive. Robin Wall Kimmerer's Braiding Sweetgrass showed me new ways to think about my relationship to the world around me. Consequently, the objects in my photographs are frequently in conversation with each other. Plastic, artificial mushrooms are nestled within the actual ones, in ways that blur the lines between the two. How does the small plastic pink mushroom feel when surrounded by dynamic pink oyster mushrooms? What happens when you cannot tell that the brown mushrooms with the dark caps situated between the Agaricus bisporus are actuallymushroom-shaped cookies?

Homegrown pink, Pigment ink on paper, 24x20 in, 2024 © Robin Dru Germany

Your research explores the tenuous border between the human and natural worlds. Can you elaborate on how you visually represent this intersection in your photography?

There is always an overlap between the natural and human worlds because we are part of the natural world, even though we like to think we are separate and superior. My images of mushrooms intend to diminish the human-made objects while elevating the natural objects. I am fascinated by the subtleties of the actual fungus in relation to the colorful plastic mushroom gadgets with which we decorate our lives. I think about whether we create bright, rough interpretations of natural forms because we want to diminish their power, generalize their complexities, and banish our fear of them. In the setting up of the scene, I imagine whether the actual mushrooms might take over my artificial ones, wrapping the mycelia around them to begin breaking down their material.

In your statement, you mention metaphors and storytelling as central elements of your work. What specific metaphors do you find most influential? And how do you incorporate them into your work?

I am a voracious reader of fiction, and I am curious about how writers devise a story that can appear to be about one very particular circumstance but, at the same time, reference a significant human theme. Sometimes, I don't even realize that writing changes my viewpoint in a subtle way. In my current photographs, mushrooms are the primary subject, with their complex structure, uneasy mythology, and current celebrity status. Humans have long found mushrooms to be scary, strange, and unsettling because we did not understand (and still don't) how they work in the larger natural world. Our fear of their unknown and underground lives has led to a desire to destroy mushrooms. I find this provides a useful metaphor for our approach to other humans who don't think or look like us. We are overcoming our fear of mushrooms with knowledge and understanding about their contributions to our wellbeing. Perhaps that way of thinking can be applied to our relationships with our neighbors, that there might be concealed undercurrents that are positive or deserving of empathy and discovery.

Fungus fish, Pigment Ink on Paper, 27x20 in, 2024 © Robin Dru Germany

Inhabited, pigment ink on paper, 27x20 in, 2023 © Robin Dru Germany

Having exhibited in various prestigious venues, how do you perceive the impact of your work on audiences, particularly in terms of raising awareness and prompting action on climate and environmental issues?

Prompting action? Probably not. But stimulating curiosity? I hope so. I would also want to spur imaginations to envision an environment with fewer borders and more integration and cohesion. I think a lot about how art provides a springboard for thinking the unthinkable. I hope to do that with my photographs, to open the door to unrealized and unthought-of possibilities.

On the same note, as a Professor of Photography, how do you integrate environmental themes into your teaching, and what do you hope your students take away regarding the role of art in addressing climate change?

There is a strong power dynamic in teaching, and I may be overly intent on providing a wide-open area in which students can explore without feeling as if they are being directed. My students can see my work, and they can ask me about my approach if they are interested. In showing examples of artists' work, I often select those who are working with environmental concerns, but I also show artists who are working with gender, race, politics, and a host of other ideas. I focus on helping students identify what they want their work to address by allowing them to engage with a wide range of possibilities.

Foot, Pigment ink on paper, 20x27 in, 2024 © Robin Dru Germany

Looking forward, what new projects or themes are you excited to explore? And how do you plan to continue pushing the boundaries of photography?

I am reading about the agency of non-human forms and what that might mean in terms of our understanding of our place in the world. I am not sure where that might take me. I have a long-term series of photographs of the natural world at night. I always wonder what mysterious things are happening in the woods and fields at night, when there are no humans interfering. (I realize that I am interfering just by being there.)The night photos seek to suggest occurrences that are unseeable, alchemical, and transformative.

Lastly, what is one piece of advice you would give to an emerging artist just starting their career?

Everyone enters the artistic process in their own way, so I am reticent to provide blanket advice to any artist. But one suggestion would be to be curious. Curiosity manifests as a question, a pondering, about possibilities. All of my favorite artists (in which I include my many artist friends) are curious people who read, look, explore, and examine every facet of their world. One of the first questions I ask of any artist when I haven't seen them for a bit is, "What are you reading, thinking about, looking at?" Their answers obviously vary widely, but they have all found some topic so intriguing that they can't stop thinking about it. Emerging artists can trust and follow their curiosity.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.