10 Questions with Junshu Gu

Intertwining discourses around labyrinths, social anxiety, and post-truth, Junshu Gu’s work is rooted in rhizome theory and draws from her 13 years of experience in interdisciplinary, culture-related media work, demonstrating profound expertise. Her practice incorporates painting, sculpture, and time-based media, appearing minimal and abstract, yet formally lithesome and precise.

She holds a master’s degree in Contemporary Art Practice from the Royal College of Art and has exhibited at various venues in London and internationally. Additionally, her moving image work has been screened at Tate Modern Lates and received numerous awards from various film festivals worldwide. She is currently based in London, continuing her artistic practice at the Conditions Studio Programme.

Junshu Gu - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Art exists in the subtle space between reality and fiction, divided only by a 'skin membrane.' The thoughts, derived from the Kyojitsu Himaku (虚実皮膜) theory by the Japanese dramatist Chikamatsu Monzaemon, reflect Junshu Gu's fascination with the delicate balance between void and reality.

Borrowing from the vocabulary of New Wave cinema, the anti-novel, and minimal music, Junshu's concerns repeatedly revolve around questions of pessoptimism, social anxiety, and the hidden initiative within chaos. She creates a sense of off-kilter rhythm where solid and amorphous energy collide. Junshu strives to address the allegorical narrative potential that emerges at the edge of chaos in the real world, aiming to examine the absence of the female flâneur and the glass ceiling that continues to hinder women in contemporary discourse.

I Hope This Finds You Well, Foil Balloon, Photography, Variable Size, 2023 © Junshu Gu

INTERVIEW

Please start by introducing yourself to our readers. Who are you, and when did your interest in art first begin?

I am Junshu Gu, an artist and writer based in London. Reflecting on the origins of my interest in art stems from my parents, who are both cinephiles. During my teenage years, their influence sparked a deep and lasting passion for cinema. On one occasion, I serendipitously rented Derek Jarman's Blue from a DVD shop. It was an unconscious decision that led to several mind-expanding hours once I returned home. I sat in front of the screen, immersed in blue (IKB 79), as though I were gazing at the sky, the sea, or perhaps a sensuous kind of void. That afternoon remains vivid and precise in my memory, and it could very well be described as my first encounter with contemporary art.

When discussing my personal journey, I often turn to Gilles Deleuze's concept of the 'Line of Flight' to describe the moments when I shifted onto new paths. My initial passion for cinema led me to work for many years as a film editor at a newspaper, with a focus on international film festivals such as Cannes, Berlin, and Venice. Then, by chance, I transitioned into the music industry, progressing from a journalist to the content director of a music streaming platform akin to Spotify in China. At the same time, my interest in contemporary art and my skill in critical writing allowed me to contribute art critiques to various media outlets.

Having had the opportunity to engage with renowned artists such as Cai Guo-Qiang, I gradually developed a growing desire to explore a more personal and subjective form of expression beyond curating and organizing content. This led me to leave my job and pursue further studies at the Royal College of Art. My previous experience in the cultural scene has provided a solid foundation, enabling me to better understand the voice I wish to express. This realization has sparked my ambition to embark on what I now consider a second life—as an artist.

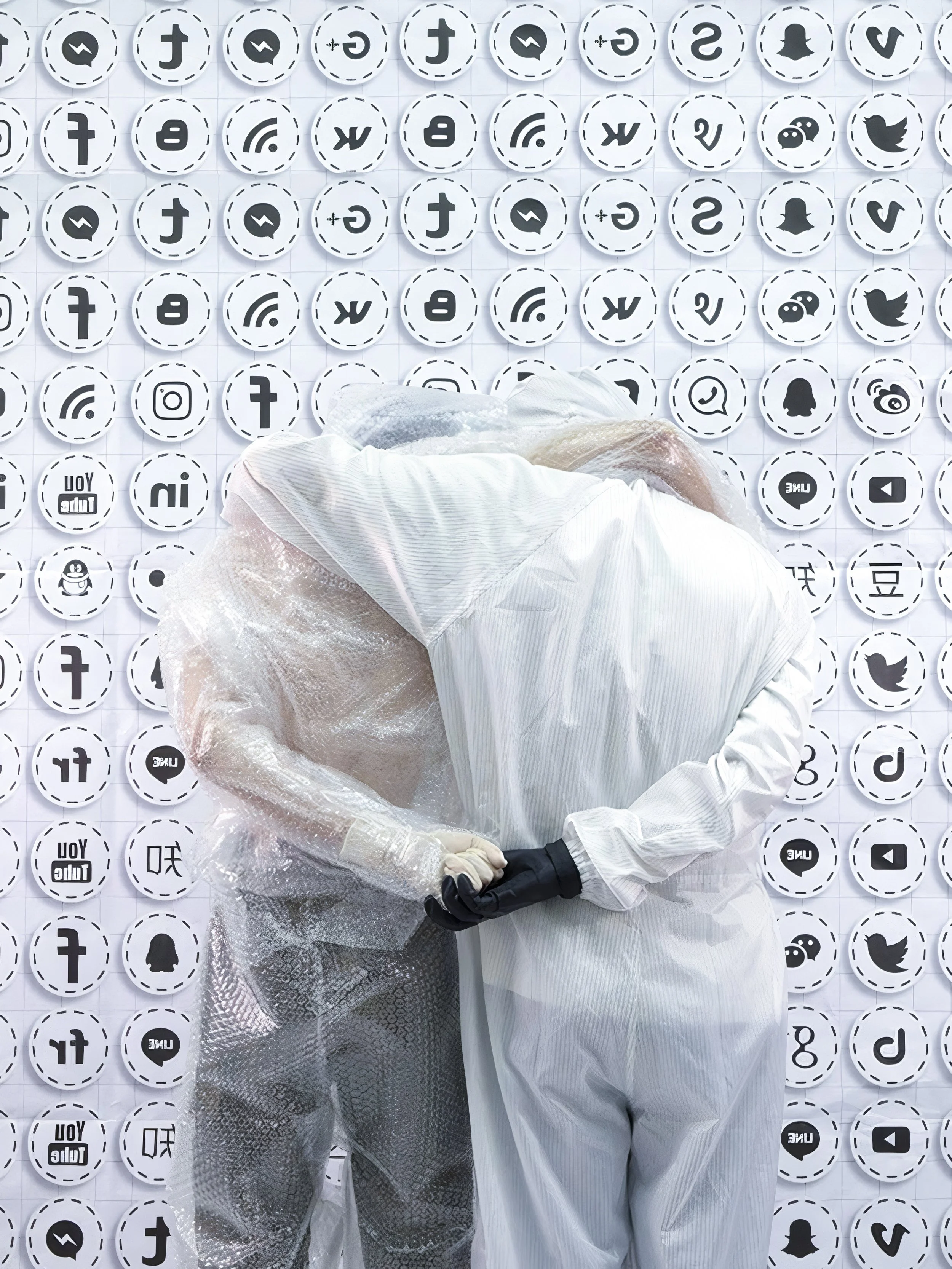

I Hope This Finds You Well, Variable Size, 2023 © Junshu Gu

I Hope This Finds You Well, Variable Size, 2023 © Junshu Gu

You received a master's in Contemporary Art Practice from the Royal College of Art. How did your studies contribute to your artistic development, particularly in refining your concepts and techniques? Were there specific moments or projects during your time there that significantly impacted your practice?

During my time at the Royal College of Art, I dedicated two years to solidifying my ambition to become an artist and finding a way to articulate my own voice. Looking back, it was both a unique privilege and an essential part of the journey. The Contemporary Art Practice program offered a compelling space where everyone arrived with their ownlabels and distinct narratives, and we were encouraged to push the boundaries of our practice by experimenting with unfamiliar mediums. This environment, characterized by freedom, became a creative playground for me, allowing me to better understand and embrace my individuality. My prior experiences across various cultural industries offered valuable insight into the constraints women face in professional contexts, and consequently, the urgency of art emerged as a key theme in my work.

One particularly unplanned yet pivotal moment in my journey didn't occur in the academic sphere but rather at the ICA during the exhibition Decriminalised Futures. In the dim, purplish-red glow of the second floor, I came across a quote from Bodies, Visibility, and Violence on the wall, stating: "If we don't make this art about our experiences, other people are going to do it." This direct and unembellished declaration prompted me to re-evaluate the profound role of personal experience in shaping collective memory and its potential to evoke empathy. It also offered clarity on a question I had long grappled with: how to reconcile the use of third-person narratives with first-person expression in my practice. I feel grateful to have come across this revelation by chance.

Your work incorporates painting, sculpture, and time-based media. Can you walk us through your creative process when starting a new piece? How do you decide which medium to use for a particular concept?

The rhythm of my creative process differs significantly from that of most people; I don't engage in simultaneous thinking and making. I've long subscribed to Nietzsche's belief that 'All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking.' This practice has been ingrained in me since my time as a journalist, and it's why I often consider myself a flâneur. Each time I begin a new project, I dedicate a substantial amount of time to reflection, which, quite literally, begins with walking. I tend to choose a part of London at random and wander aimlessly. This state of mental openness, combined with spontaneous moments of inspiration, allows me to clarify the themes I wish to explore, define abstract visual symbols, and select the most suitable medium. Only when I have established a clear conceptual framework do I begin the physical process of making.

Consequently, my work is concept-driven, unbound by any single medium, with choices that often feel intuitive or serendipitous. For instance, in my project, I Hope This Finds You Well, which focuses on the theme of anxiety, I was influenced by Deleuze's reading of Francis Bacon. Deleuze noted that Bacon often employed objects such as mirrors, basins, or umbrellas as vanishing points in his compositions, which he saw as the origin of anxiety. During one of my walks, I passed an optician's shop and was reminded of how, during an eye exam, the vanishing point is often representedby a balloon. This inspired me to use an enlarged, abstract mirrored balloon as a symbol of anxiety. I am deeply drawn to these spontaneous connections, which, for me, are the most enjoyable aspect of the creative process.

Working with such different mediums is quite challenging. How do you approach each one? Do you find any difference in your creative practices or routines when working with these mediums?

Engaging with different mediums is undoubtedly challenging, as it demands the acquisition of new skills, yet it is precisely the distinct messages and rhythms each medium conveys that continuously reinvigorates my practice. With a background in film and writing, I'm well-versed in the art of storytelling through the camera, a narrative technique I am particularly comfortable with. At the same time, I am captivated by the construction of minimalist space—artists like Ian Kiaer and Cathy Wilkes, both of whom I hold in high regard, are key inspirations. I am deeply drawn to a certain visual rhythm, which has naturally led me towards incorporating mixed media painting and sculpture into my work. Derek Jarman, who, despite being a painter, began his career in stage design, is another influential figure. Ultimately, I view all mediums as equal tools for expression. When you are fortunate enough to find the right medium, it speaks for itself, opening new spaces and possibilities.

Rhizome theory plays a significant role in your work. How do you apply this concept in your practice?

From 'Fold,' 'Rhizome,' to 'Line of Flight,' this series of terms, frequently found in Deleuzian philosophy, forms the conceptual backbone of my practice. The energy that emerges from anxiety creates folds, which in turn trigger an instinctual human drive to escape. The paths of escape are multiple, unstructured, and rhizomatic, offering a range of possibilities. My own life trajectory is, to some extent, an embodiment of this theoretical framework. I also believe that, in the contemporary context, this concept applies universally. As a result, I have continually sought ways to translate these abstract ideas into visual form, creating a new order out of chaos and fostering a unique mode of empathy with the audience.

I Hope This Finds You Well, Variable Size, 2023 © Junshu Gu

Your art often explores the delicate balance between reality and fiction, inspired by the Kyojitsu Himaku theory, as you mention in your statement. How do you navigate this "skin membrane" in your work, and how do you decide what elements of reality to include or abstract?

This theory traces its origins to Chikamatsu Monzaemon, an Edo-period playwright often hailed as the Shakespeare of Japan. Chikamatsu sought to explore the complex relationship between illusion and reality within the theatre, asserting that the true essence of art lies in the 'skin membrane,' the momentary transformation between the two. I have long been, both consciously and unconsciously, captivated by this liminal space—fascinated by the threshold between chaos and order, reality and fiction. When I first encountered this theory, it immediately resonated with my own artistic concerns. Consequently, I have developed a strong interest in materials that create reflective surfaces or produce visual dislocations.Yet, in the process of creation, reaching this threshold often requires more than just selecting the right medium; it demands ongoing experimentation to uncover the critical point. For instance, by significantly enlarging or shrinking an object or a real-life scene, it can reach a scale where it becomes unfamiliar, even surreal. This, for me, is the most compelling part of the process, and it is precisely the concept that Michelangelo Antonioni explores in his film Blow-Up.

Social anxiety and the concept of pessoptimism are recurring themes in your work. What draws you to these subjects, and how do they manifest in your artistic expression?

While I am deeply drawn to minimalist and abstract forms of expression, the real-world concerns underpinning my practice are highly specific. Central to my work is an examination of the subtle, often unspoken anxieties that individuals face within the contemporary landscape—particularly the persistent need to process and negotiate multiple streams of information simultaneously. These emotional states resist easy classification within binary notions of joy or sorrow, instead existing within a more nuanced spectrum of experience.

Frankly, my initial creations did not engage with the framework of feminism. However, my awareness shifted when I encountered boundaries in the real world as a woman. It is at that moment that questions arise. It is akin to living in a healthy body, where individual parts are not acutely felt, and everything operates naturally. However, when there is an issue, even something as minor as a cut on your finger, that part's presence is immediately magnified. Encountering the glass ceiling in the workplace makes these limitations tangible, preventing women from fully playing the roles they deserve. This imbalance is what I, as an artist, now seek to express.

The Morning Is Dangerous, Acrylic, Film, Mix-media, Variable Size, 2024 © Junshu Gu

The Morning Is Dangerous, Acrylic, Film, Mix-media, Variable Size, 2024 © Junshu Gu

Your moving image work has been showcased at prominent venues and festivals like Tate Modern Lates. What did you learn from these experiences? How does the public's response impact your work?

I feel truly fortunate that my moving image work has had the opportunity to be shown in various contexts and reach diverse audiences. The story begins in 2022, in Barcelona, where my phone was robbed by a man on a motorbike. For a self-organized woman who prides herself on being a flâneur on solo trips, this experience dealt a blow to my self-perception and proved traumatic. This prompted me to question the definition of the flâneur.

During my research, I encountered something unexpected. In early French, the feminine equivalent of flâneur was not a female flâneur, but an indoor lounge chair. The absence of women was not confined to the 19th century but persists in contemporary discourse. Two months later, I returned to Paris, the birthplace of the term. In the aura of Walter Benjamin, I filmed this moving image work. Through a non-linear narrative, following the rhythm of Virginia Woolf's Street Haunting, the video shares thoughts on the coexistence of resilience and vulnerability. The title is a quote from Nietzsche, while the word 'but' introduces a new line of questioning.

The responses from viewers have offered me valuable insights, as I had embedded numerous hints within the work—forinstance, the duration of 4'33" was a deliberate reference to John Cage's silent piece, symbolizing the absence of female flâneur. The fact that these subtleties were recognized by the audience fills me with immense gratitude. Ultimately, this experience has shown me to never underestimate the audience and to stay confident in trusting my own creative voice.

As you look ahead, what themes or concepts are you interested in exploring next? Are there any upcoming projects or exhibitions that you're particularly excited about?

My work continues to focus on themes such as societal anxiety, yet I am eager to approach these narratives from new perspectives, exploring a broader range of mediums. Since April, I have been collaborating with a film crew to interview key figures from electronic music culture, with the aim of producing a piece that examines the interplay between anxiety, space, sound, and ritual. The project is still in progress, and the process has been incredibly exciting—I look forward to seeing it take shape in the near future.

Fingerprint Tells, Latent Fingerprint Lifting Pads, Mixed media, 5×6 cm, 2019 © Junshu Gu

Lastly, given the evolving nature of art and media, how do you envision your practice evolving in the future? Are there any new techniques or interdisciplinary collaborations you're keen to explore?

As a contemporary artist, maintaining a sharp sense of observation and staying attuned to the ever-evolving world is essential—this awareness closely parallels the mindset required of a journalist. Perhaps this is one of the subtle advantages that has allowed me to shift between different fields. The way people consume and process information is constantly changing, and I am interested in discovering flexible and engaging methods to respond to these shifts.

Additionally, I have recently revisited an earlier project that also focuses on anxiety, using dermatophagia (compulsive skin biting) as a point of entry. I am currently conducting further research and gathering samples, with plans to collaborate with mental health institutions. My aim is to refine this project, potentially developing it into an artist's book or finding new modes for dissemination.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.