10 Questions with Peter Politis

Peter Politis (b. 1989) is an artist from St. Paul, Minnesota, USA. He graduated in 2011 from St. Olaf College, Northfield, USA, with a B.A. in Asian Studies.

Peter Politis - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

With inkwork, there is no erasing; once laid down, a line is final and can only be added to. The contrast between black and white tends to emphasize shape, while the fluidity of the applied ink itself emphasizes motion. Evocative inkwork can be considered, and of course, this is a single definition, as the distillation of what we call "thought" into something almost purely kinetic- though not necessarily focused or premeditated.

This free, kinetic form can serve as the skeleton, or blueprint, to painstaking work, as in the minutely detailed calligraphic signatures of Ottoman sultans or the stone-hewn, painted poetry adorning the walls of the Alhambra in Spain- the latter example being a representation of inkwork. As humans, we don't live our lives in the midst of a never-ending burst of spontaneity and reaction; most of us aspire not to behave like amoebas. At the same time, our minds are incapable of endless, measured repetition. Thus, throughout the day, these two exclusionary forces alternate and converse with each other, each picking up slack from the other when it begins to tire.

Humans exist within the strictures of time, and we cannot erase events, just like an artist cannot erase ink. Our lines are laid down first of all, and we are made to build from them however best we can.

Boxer with cigarette © Peter Politis

INTERVIEW

First of all, why are you an artist, and when did you first decide to become one?

It's hard to pinpoint an exact reason "why". I've been drawing in some form since kindergarten, like most people. Creation is not an act reserved for a certain subclass of person; anyone can express thoughts and emotions in ways that can be considered "artful". Some are chefs, some make clothing, etc. To my mind, the most dedicated "artists" in this world are the artisans who have perfected their craft while working outside of the formal art world. Their daily job is creating and subsequently selling traditional paintings, carvings, or clothing, usually to tourists or wholesalers. It's a pragmatic work ethic, which is something easily forgotten in the Western world, where we tend to elevate the act of creation to something almost sacred. For an individual to consider themselves something of a "working artist," I think, implies a healthy application of mundane direction to the creative process, steady repetition. For me, this started maybe four years ago.

What is your personal aim as an artist?

Abstraction and improvisation are what I'm good at, but an effective artist's ability to harness looser styles runs parallel to their ability to express subjects straightforwardly. A major personal goal is to become technically proficient in a more traditional way (perspective, anatomical form, shadow, etc.) and not be locked solely behind obtuse means of expression. I think it is too easy in today's world for artists to feel obligated to overdevelop a personal style, a "brand". There is, unfortunately, this pressure.

Man arguing with dog © Peter Politis

How did your practice evolve over the years? And how would you define yourself as an artist today?

When I was younger, I mostly drew sequential art: comics and characters. My best friend (also an artist) and I often spent the weekends creating videogames or designing/playing an illustrated trading card game we had created. There would usually be some sort of narrative involved, some alternate reality ensconced. It wasn't until college that I began to read into art theory for my studies and learn more about art history- particularly that of the early 20th-century avant-garde. After graduation, I became more "professional" with everything: painting murals, making signs, general contract work, and sales.

You graduated in Asia studies. Does Asian culture and art influence your work in any way?

That's broad; "Asia" encompasses well over half of the world's population. I think most artists are influenced by other cultures, at the very least, because artists are attracted to novelty (though it's usually more than this). I suppose, personally, that becoming familiar with Eastern (Chinese) calligraphy and scripts has played a major role in the 'rhythm' of my drawings. At the same time, in college, I was originally set to become an art historian of Islamic Architecture, so working in fine detail while cultivating a general avoidance of empty space (horror vacui) probably stems from that period of my life.

What is your creative process like? And how did you evolve this way of working?

There are two main ways in which I develop large-format drawings; these are by no means mutually exclusive. The first technique is to draw a kinetic, open-ended "skeleton" with simple lines, rotating the paper frequently. I keep fleshing it out until a loosely figural interpretation can be adapted- and then complete the space accordingly. The second technique, which produces more literal depictions, is fairly common- sketching a basic drawing in advance with a pencil and then adapting it, along with considerable improvisation, with a pen. I don't think there was a conscious evolution of technique, though I do have a log of the specific patterns that "look good", and a memory of the types of patterns that do not. There was also a lot of trial and error in figuring out more technical things, e.g., which ink to use with specific paper types, which gauges of technical pens snag and bend on cotton fiber, which method of ink application yields the most uniform fills, etc.

Tripartite Growth© Peter Politis

Hunter © Peter Politis

Nightmare © Peter Politis

Mountain Stream © Peter Politis

As you mention in your statement, “With ink there is no erasing; once laid down a line is final, and can only be added to”. What aspect of your work do you pay particular attention to?

The larger drawings can be almost painful to make, sometimes, because of the amount of repetition and detail involved. The major challenge is keeping your mind alert enough during the process. If you drift off mentally and botch a textured section for 15 minutes, the entire image might be harmed. It's like a polygraph test: your mental state is recorded in ink. As I mentioned in the artist's statement, lines cannot easily be subtracted from the paper in the same way that errors in a painting can be concealed. Whatever you put down is soaked into the fiber.

What are the main themes behind your work?

Figures. Depictions of faces and bodies. Something familiar for the viewer to latch onto apart from the abstraction of shadows, depth, etc. It's an overstated precept, but it's usually true: there must be a balance of chaos and order.

What do you think about the art community and market? And how did your perception change over the last years due to the pandemic?

In the United States, if I had to guess, only about 1% of professional artists derive their income solely from sales; the careers of the rest are diversified- art teaching, live painting, murals, personal online stores, etc. I didn't see much of this paradigm-change during the pandemic, with the exception of the tech/crypto quarantine boom ushering in the tentative feasibility of NFTs. Most galleries and professionals still don't understand how best to capitalize upon blockchain art (basically the digital version of limited-edition print runs); it might not be worth investing in the development at all. Who knows where things will be in 5 years?

Alien © Peter Politis

Mad Mouse © Peter Politis

Did you participate in any online exhibition or art fair? And what are your thoughts on the increasing popularity of digital art and art exhibitions?

Not yet, though I would certainly opt in if given the opportunity. As for my feelings about digital exhibitions and the display of art online in general, they are somewhat mixed. On one hand, the exposure it allows artists and their representatives is unparalleled and global. Painters from one side of the world can draw inspiration from their counterparts on the other side and communicate/collaborate if they choose. This was not so easily possible in the past and is, I think, an interesting development. On the other hand, the limitations of a pixel-based screen introduce a sort of artificial selection pressure on the sort of art that becomes popular and, therefore, most visible- certain forms, sizes, colors, and techniques just look better on an OLED cell phone screen than others do, even though in-person the images might not be so striking. And vice-versa. Artists feel pressured to produce works that will look impressive and neat when scaled to the basic dimensions of Instagram posts, for example. I don't think this is a positive thing for the development of young artists as it inevitably homogenizes the type of work that becomes well-shown online. Curators will be forced to adapt to what is algorithmically popular; it doesn't work the other way around, sadly.

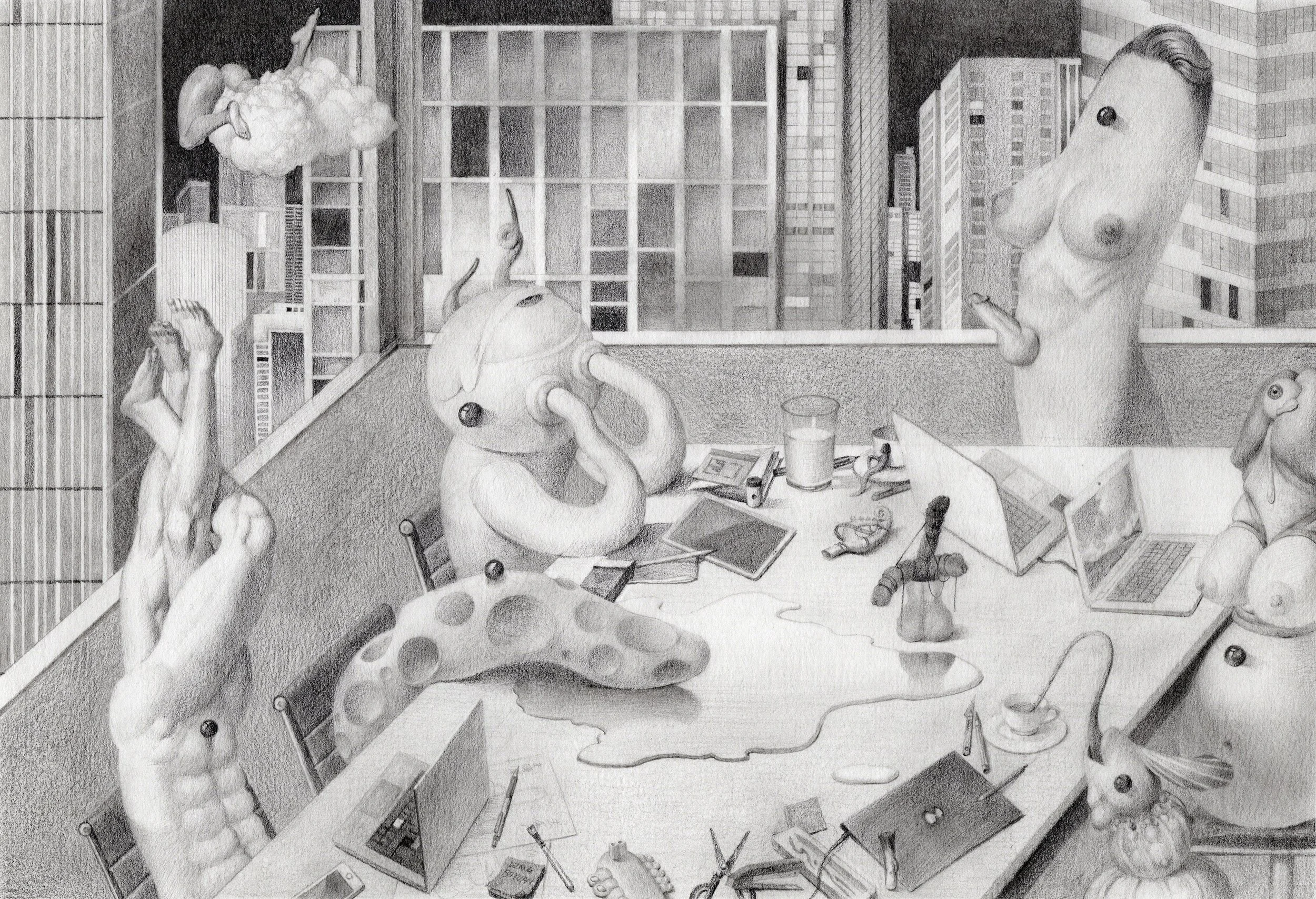

And lastly, what are you working on now, and what are your plans for the future? Anything exciting you can tell us about?

I'm trying to get back into working with color more, perhaps adapting my drawings and materials to watercolor techniques. And I think that having a classical base to work from is important. Lately, my studio work has been focused on realistic figural and scenic drawings. Admittedly, these are nowhere near ready to be shown professionally (they never may be).