9 Questions with Djipco - ORIGINAL issue

Djipco is a canadian artist based in Montréal (Québec, Canada) featured in Al-Tiba9 ORIGINAL issue.

Jean-Philippe Côté is an artist based in Montréal (Québec, Canada). Algorithms always drive his visual and interactive work. Using open-source software and pieces of “obsolete” hardware, he puts together interactive installations that bring back a sense of tangibility to this otherwise artificial, virtual, and augmented world of ours.

Jean-Philippe leverages his early years as an award-winning developer to devise algorithmic approaches to creating art and re-shaping reality. It makes him a respected contributor to the open-source community, especially in the fields of creative coding and physical computing.

His subject of choice is the human body, which he often draws using micro or macro line segments. While figurative, his work challenges perception. The viewer’s brain is asked to fill in the gaps, and one often needs to change his point of view to appreciate the work entirely.

His work has been featured on three continents in venues such as the Arsenale di Venezia, Minneapolis’ Walker Art Center, Düsseldorf’s Capitol Theater, Montreal’s Museum of Contemporary Art and Société des arts technologiques (SAT) or Fukuoka City’s Science Museum.

Interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj.

Jean-Philippe, you are an interactive and visual artist. How did your education, experience, or training develop your skills?

I don't have any proper training in fine arts. I basically stumbled my way into art. By that, I mean that there was never an effort, conscious or otherwise, to fit in or diverge from a specific movement, technique, approach, or aesthetic. Obviously, I do have my own biases and preferences. However, they do not come from art training, which, let's face it, can sometimes be more of a curse than a blessing. Honestly, I wish I could draw, but not being able to draw properly is what led me to develop my creative ways. Most of my art is done through prosthetic devices of my invention. Creating assistive software and hardware contraptions, is in itself, part of my artistic process.

My formal education is in media and communication studies. I now realize that this has profoundly shaped the way I work. It may sound like heresy to parts of the art world, but factoring in the viewer or interactor is an integral part of my process. Never have I worked in this mythical and pure artistic bubble forgetting that my work will ever be seen. Isn't this romantic notion somewhat archaic anyhow?

On the contrary, I see my art as a two-way street, much like communication. The goal is not necessarily to deliver messages but, instead, to provide experiences. If the audience cannot connect, on any level, with that experience, I consider it my failure. This has to come from viewing art as communicative. However, that does not mean one has to create art for the audience or, worse, for all viewers. My art comes from my interests and sensibilities. It is selfish at the beginning of the creative process but, hopefully, engaging to others at the end.

Please describe the intention behind your art. How do you express this intention successfully?

One very appealing definition for art is the one proposed by Jesse Prinz, professor of philosophy at City University New York. He suggests that what separates art from the rest of reality, is the intention of its creator to inspire wonder. I firmly adhere to that view and always intend for my work to trigger emotions such as curiosity and wonder.

I like my art to trigger intrigue and to have a certain playfulness to it. Let's have the viewer play an active role. Doing so often means aiming for that fine line between abstraction and representation and letting the audience do the rest of the interpretation work.

Photo courtesy Jean-Philippe Côté©

As an artist, tell us about the relationship between human and the machine. Could you expand on the Innocent Surveillance interactivity?

Humans and machines have always had a love-hate relationship. There are times in history when technology tended to be glorified and others when it tended to be vilified. In the case of surveillance technology, many were fearful or outraged when cameras started to appear in public spaces. But then, everyone started to have surveillance capability in their pocket. We started shooting everything and anything all the time, and the fear of Big Brother faded away as we, collectively, became Big Brother, for better or worse.

I presented Innocent Surveillance at the University of Massachusetts and had groups of art students come by with their teachers to try out the installation and discuss it. The impression I got from the students was that "surveillance" was not an issue for them. Obviously, this is a gross over-simplification, but I believe there is some truth to that. It seems as though the idea of a "right to privacy" means something different to a generation that has always mediated itself daily. This made me feel quite old fashioned and invited me to rethink my frame of mind on this topic.

I think that the pendulum may soon start to swing back the other way. While surveillance technology is somewhat socially accepted (or at least tolerated), the analysis of the captured data with the means of artificial intelligence is something new and something that should be looked at with utmost scrutiny. We need to educate ourselves as to the capabilities of artificial intelligence because its advent is a pivot point in the trajectory of humanity. I may sound grave, but one cannot stress enough how far-reaching and world-changing AI really will be.

You created 2500 live portraits of willing passersby. Amongst those, pairs of portraits were carefully selected, colorized, and juxtaposed to create the ghostly artifacts. How can you describe your complex artistic production and technique for our readers?

I always get lots of technical questions from the audience about my work. Understanding how the machine works is something very appealing to many (including myself!), and one way my art triggers curiosity. Generally speaking, people want to know what makes the Mechanical Turk tick. We want to see the magician's trick but, just as much, we want to believe the magic.

Early on, I didn't want to dilute the magic by revealing too much. However, revealing the tricks also offers a positive upside: people become less intimidated by technology. That is a good thing. Once in a while, I will read comments on social media from prior visitors explaining how they decided to explore some of my techniques in their projects. This is very rewarding. This is why you will find all sorts of technical details about my projects on my website, on github.com, and tinkercad.com.

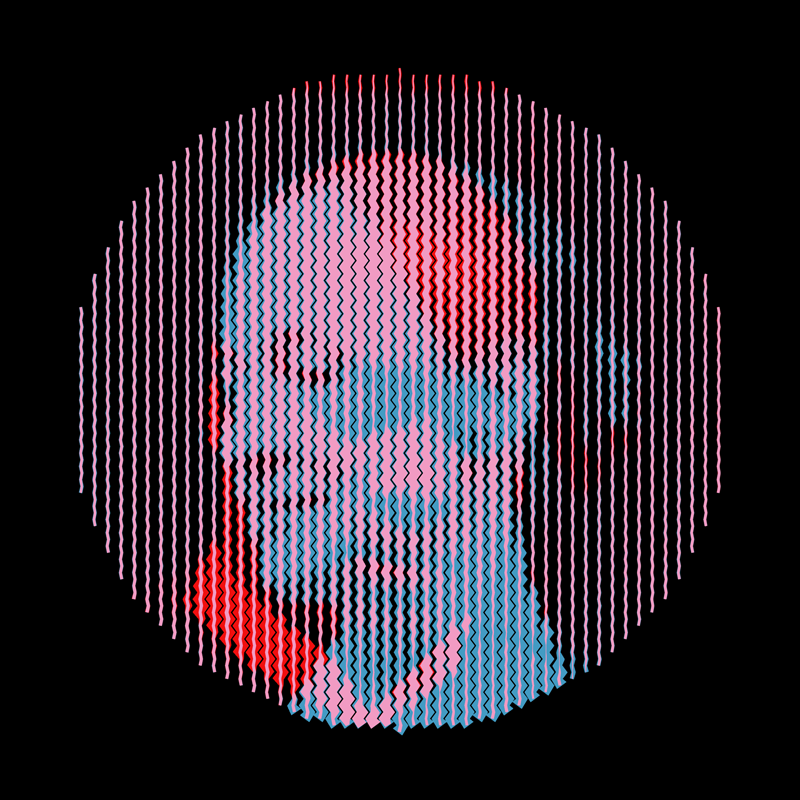

Binôme 1570+1577

Binôme 1009+1036

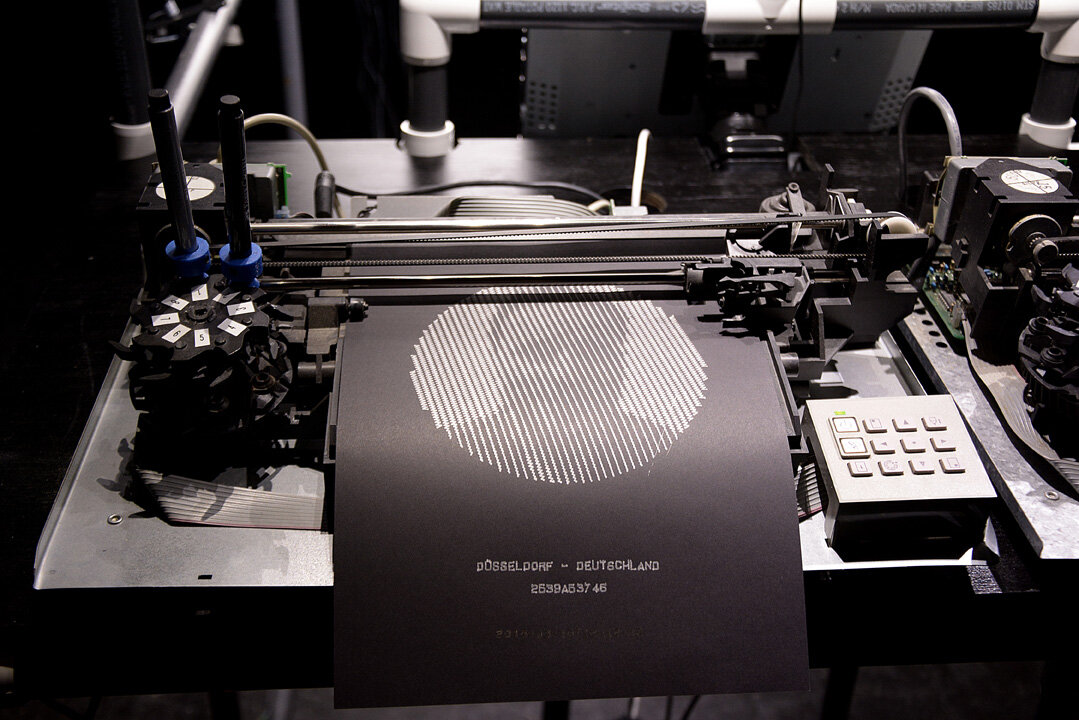

In the specific case of Innocent Surveillance, I used a 75$ off-the-shelf webcam to film passersby. Each frame of the video feed is analyzed by a computer vision library called OpenCV. The library uses machine learning to identify frames with faces in them and to extract the largest face found. The face image is saved to disk for further processing. Then, using a bit of math, I plot the paths of a bunch of lines on top of the saved image. The lines are straight when the underlying pixels are dark and wiggle when the underlying pixels are light. Using this data, I use a 3D library called BabylonJS to draw and animate the lines of the portraits. The result is projected onto a circular screen. Note that all the software used in the installation (including the GNU/Linux operating system) is free, open-source, and accessible to anyone. The computer and webcam are hidden inside a wooden cabinet expertly crafted by my friend Benoit Lavigne. This was the original concept of the interactive installation, and people enjoyed it. After a few months, when the installation was decommissioned, I was left with thousands of portraits and figured I should do something with them. This was when I started combining them, averaging them, colorizing them. It was fun to explore this raw material and reveal its hidden possibilities. This ended up being the Binôme series presented here.

I have seen your work during the ceremony award of the Arte Laguna Prize 2019 in Arsenale, Venice. How did the visitors interact with your work? Is public interaction different in a small gallery?

Arte Laguna was a fantastic experience. Presenting your work in a 900-year-old venue is not something you expect to do when you were born in "the new world". Winning a Grand Prize was also something completely unexpected. I almost missed the awards ceremony because I was so caught up chatting with people trying out the installation.

The piece presented in Venice (Yöti) was a precursor to Innocent Surveillance and later works. This is where I first used the jagged lines as the primary representation technique. While the exhibition space was beautiful and did enhance all the works presented there, it is the people that I will remember most. Their openness, curiosity, and generosity made the experience memorable. Welcoming so many visitors at the same time means the experience is less intimate than in a small gallery, but what it lacks in intimacy, it makes up for in energy.

Of course, a more prestigious venue does bring with it more opportunities. Case in point, it is during this event that I met Vasili Tsereteli, executive director of the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, who invited me to present the installation in 2021.

Going back to the people of Venice, I was lucky to have met and exchanged with them and felt very sad during the floods that followed the exhibition and even worse when all hell broke loose in March of this year.

Let's say you have an exhibition proposal for coming up months. What does your process look like – from creating or adapting an artwork, to the final exhibition show?

So far, I have mostly worked the other way around. That is, I like a piece to be finished before I start pitching it and showing it. This is even more true for complex projects like interactive installations. I guess I'm a bit of a control freak in that sense. I find it very hard, creatively, to put myself under a deadline (even though, at some point, I need to if I ever want to deliver). Even worse, I usually have no idea where I'm going when I start a project. I cannot imagine myself doing commission work. This would be too much stress and constraints. I prefer to finish projects on my timeline and then find them suitable homes to be presented in. This may sound overly independent, but it is just a reflection of my insecurities.

Today, the world is facing the pandemic COVID-19. What is a typical day like for you? How do you continue doing your art under these circumstances?

I don't. For whatever reason, I have not worked on my art since this all started. I will get back to it but, for now, this is not what drives me. Instead, I have been sinking a lot of time in a pet project called WebMidi.js. It's a software library that allows musicians to connect their electronic instruments to web browsers. It began life as a by-product of my master's research and gained quite a bit of popularity since then. I had been meaning to work on it for a while and figured now was my chance. This side project is probably an excuse to procrastinate, but I guess it's okay to drift away once in a while.

They say if you could be anything but an artist, don't be an artist. What career are you neglecting right now by being an artist?

Well, "they" are wrong. I spent 20 years not being an artist and it is by choice that I finally became one. Actually, it was a pretty self-conscious act. After finishing my master's degree 7 years ago, I decided that I would become an artist. I added the word "Artist" in my email signature, and that was it. At first, it felt strange to claim this title, but I guess acknowledging it was the first step. Since then, starting with no experience and having no training, I did my thing and applied to every art festivals and events I could find and managed to, somehow, travel the world. I guess art is like anything else; you have to work hard at it (and have a little luck once in a while).

I'm still not 100% convinced that I qualify as an artist, but I am trying, starting this Fall, I will actively be fighting this impostor syndrome by beginning a research-creation doctorate program in art studies and practices. In a few years, when I am done, I will be a true artist and, if not, at least I'll be a doctor.

What current project are you working on?

My next big project involves repurposing old, still working, iPhones into sculptural installations. The installations are interactive and use networked artificial intelligence to generate portraits of visitors and other imagery. This project has been going for quite a while now. Programming the communication between the devices is done, but I'm still struggling with the AI. This is new stuff for me, and I will need more time to get it right.

As an artist, learning when to let go, is an oft-overlooked skill. It cannot be too early, but it shouldn't be too late either. With this new project, I am still somewhere in between, but I will get there…

Photo courtesy Jean-Philippe Côté©