10 Questions with Hanqi Li

Al-Tiba9 Art Magazine ISSUE18 | Featured Artist

Hanqi Li is a practice-based media artist and researcher who holds an MA in Interaction Design from UAL and currently splits her time between London (UK) and Shenzhen (CN). Li’s work primarily engages with interactive art, narrative films, generative art, and 3D rendering, while her research explores media archaeology, speculative fiction, and the intricate relationship between nature and technology, with a specific focus on environmental issues such as the Guiyu e-waste crisis and the infrastructures of science and technology in China. Li’s work has also been showcased in several international exhibitions, including the renowned Ars Electronica Festival in 2023, and was selected as one of the 10 entries for the Lumen Prize sponsored by Onkaos in 2023.

Hanqi Li - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Hanqi Li’s practice critically explores the evolving relationship between nature and technology through the lenses of media archaeology and speculative fiction. Her work investigates the environmental consequences of technological systems, with a particular focus on the Guiyu e-waste crisis in China. By interrogating the entanglement of human-made infrastructures with natural ecosystems, Li sheds light on the often-overlooked material traces and ecological impacts of digital technology.

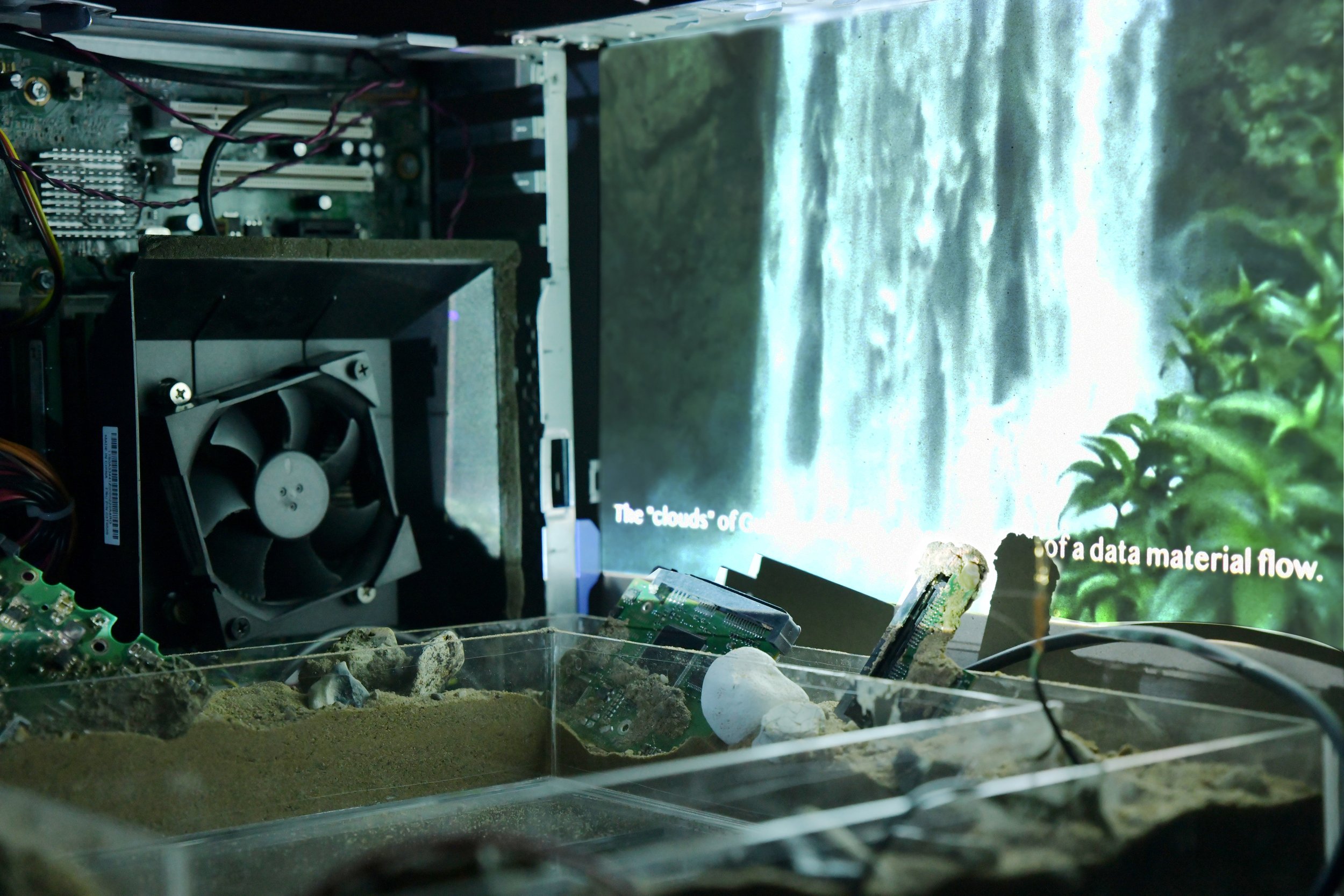

Li’s artistic approach is deeply material-driven, incorporating multisensory installations, screen-based media, and physical materials to render invisible technological processes tangible. In her Sensing the Toxic Guiyu project, she used circuit boards corroded by acid solutions to evoke the destructive transformation of e-waste. In Down to the Karst Landscape project, she employed sand, stone, and water to simulate the geological layers of Guizhou’s landscape, illustrating the interaction between mining activities, cloud computing infrastructure, and natural formations. By physically recreating these entanglements, her work challenges audiences to reconsider the material realities behind digital infrastructure and its long-term environmental footprint.

Driven by a desire to provoke thought and dialogue, Li aims to use immersive installations to create opportunities for reflection on the hidden infrastructures shaping the digital world. By bridging speculative storytelling with physical engagement, she invites audiences to question the sustainability of technological progress and the uncertain future of our planet in an era of rapid transformation.

Sensing the Toxic Guiyu, Mixed madia, PCB boards, 55x80x120 cm, 2023 © Hanqi Li

Sensing the Toxic Guiyu | Project Statement

Sensing the Toxic Guiyu is an olfactory installation that used odor chemical essential oils combined with sculptural models and speculative films, which aim to simulate the toxic area of China’s biggest e-waste town. The stability of heavy metals suggests they will persist beyond the Anthropocene. When dismantling, burning, and degrading into simpler metallic elements and chemical forms, they became invisible. They would diffuse into the wider environment, even the biological chain and beyond, having a deep time scale’s influences. However, the smell of e-waste could become the invisible element to connect human’s body and the dead media, which aimed to question about how Guiyu as a shaded place on the otherside of world could be experienced? What kinds of uncertain future would it have?

Sensing the Toxic Guiyu, Mixed madia, PCB boards, 55x80x120 cm, 2023 © Hanqi Li

AL-TIBA9 ART MAGAZINE ISSUE18

INTERVIEW

Let's start by introducing yourself. Who are you, and how did you develop into the artist you are today?

My name is Hanqi Li. I'm a media artist and researcher working between London and Shenzhen. My practice focuses on the hidden material side of technology—things like data centres and e-waste problems and my work across different formats, including interactive installations, narrative films and 3D rendering.

I've always been interested in science fiction, and that curiosity led me to explore how technology shapes our world, often in invisible or overlooked ways. Studying Interaction Design at the University of the Arts London gave me the tools to experiment with different media and connect research with experience. Over time, I became more focused on environmental and geopolitical questions—especially how technology leaves traces on the land and in our lives, which is the core of what drives my work today.

Green Election Urban Mining, 2023 © Hanqi Li

Working between London and Shenzhen, do you find that your geographic locations influence your artistic themes or methodologies?

Shenzhen is a city that's deeply embedded in digital technology. It's home to Huaqiangbei, one of the world's largest electronics markets, and surrounded by countless factories that produce the components behind our phones, computers, and other everyday tech. Being in that environment, you're constantly reminded that all these digital systems have a physical side—there are hands building the devices, materials being extracted, and waste being created. That awareness has pushed me to focus on the materiality of technology and the hidden infrastructures behind it.

In contrast, London gives me more space to reflect and research. It has a strong academic and art community, which helps shape the theoretical side of my work—things like media archaeology, speculative fiction, and critical design. So, in a way, Shenzhen gives me the raw material and context, while London gives me the tools to process and reimagine it.

Working between these two places has helped me build a practice that's grounded in real-world systems but also open to critical and speculative thinking.

Your art spans multiple formats, from interactive installations to narrative films. How do you decide which medium best fits a particular concept?

For me, the choice of medium always comes out of the research. My practice is very research-based—whether it's about digital infrastructure, environmental impact, or speculative futures. One thing my tutor once said inspired me a lot: "Once you get your hands dirty, you'll start to see what the work needs."

I often need to experiment—build quick prototypes, test different formats—before I fully understand what the piece is asking for. Some concepts demand spatial or interactive experiences, while others unfold better through narrative or generative visuals. So, the decision isn't fixed or formulaic, and It's very much a part of the research process itself.

Down to the Underground Karst Landscape, 2023 © Hanqi Li

Down to the Underground Karst Landscape, 2023 © Hanqi Li

Your work explores the intersection of technology, media, and the environment. What initially drew you to these themes?

I think it started with a mix of personal experience and curiosity. Growing up in China, I was always aware of how fast technology was changing everything around me—especially in cities like Shenzhen, where new devices, factories, and systems appear almost overnight. But it wasn't until I came across places like Guiyu, known for e-waste processing, that I really started to question what happens after technology becomes obsolete. That was a turning point for me—realizing that behind every "smart" system is a chain of materials, labour, and environmental impact.

At the same time, I've always been drawn to science fiction—not just as a genre, but as a way of thinking. Sci-fi invites us to imagine alternate futures and question the systems we take for granted. When I discovered ideas like media archaeology and concepts like Bratton's The Stack, it gave me a framework to connect those interests—to think critically about how digital infrastructures shape both our present and the environment around us.

Let's talk about Sensing the Toxic Guiyu. The installation uses olfactory elements to engage viewers. What role do sensory experiences play in your artistic practice?

Sensory experience plays a really important role in my practice, but to be honest, I didn't set out from the beginning, intending to use olfactory elements in my work. It actually came from my field research in Guiyu. When I visited the site in person, the thing that struck me the most wasn't what I saw—it was the smell. The air was filled with a strong, almost suffocating mix of burning plastic, metals, and chemicals. It surrounded your body and stayed with you even after you left.

That experience made me realize that if I wanted to communicate the reality of Guiyu, I couldn't just rely on visuals or data—I needed to bring that sensory intensity into the installation. So, in Sensing the Toxic Guiyu, I introduced olfactory elements to recreate that atmosphere and invite the audience into a more embodied experience. I wanted them to feel, even for a moment, what it's like to stand in that kind of environment. For me, sensory elements like smell really help translate abstract issues like e-waste or environmental toxicity into something more immediate and human, which also promotes a close distance between the audience and the work.

Down to the Underground Karst Landscape, 2023 © Hanqi Li

The Guiyu e-waste crisis is central to this project. What inspired you to focus on this issue, and what do you hope audiences take away from it?

The e-waste crisis in Guiyu has actually been going on for decades—it's not a new issue. What drew me to it wasn't just the environmental damage but also the layers of silence and erasure surrounding it. In recent years, the Chinese government has publicly claimed that the e-waste problem has been properly handled, and access to the area has become more restricted. Media coverage is limited, and there's an effort to portray Guiyu as a place that's been "cleaned up."

But when I went there myself for field research, I saw a very different reality. It was still easy to find mountains of discarded plastic casings, broken circuit boards, and other remnants of electronic waste. What struck me even more was the silence—both from the people living there and in the broader narrative. Many locals seemed resigned to the situation, and their stories were missing from the official version of events.

This experience made me feel a responsibility to create a space where these hidden realities could be seen, felt and questioned. Through this project, I don't just want to raise awareness about Guiyu as a specific site of e-waste processing—I also want to encourage audiences to think about the systems that produce this kind of environmental and social invisibility. Where do our devices really go when we're done with them? And who bears the cost? Therefore, I hope the work gives audiences a sense of proximity to something that's often kept out of sight—both physically and politically—and inspires them to look more critically at the afterlives of technology.

Your projects often blend speculative storytelling with real-world environmental concerns. How do you balance fact and fiction in your narratives?

For me, fact and fiction aren't opposites—they're two tools that help me explore different layers of truth. A lot of my work is grounded in real-world research: site visits, field notes, academic theory, and lived environmental issues like e-waste or data infrastructure. But sometimes, facts alone aren't enough to express the emotional, ethical, or speculative dimensions of these systems.

That's where fiction comes in. I use speculative storytelling as a way to stretch the narrative—to imagine alternate futures, reframe present-day issues, or highlight the parts that are often left out of official records. It's not about escaping reality but about expanding how we see it.

For example, in my work related to cloud computing in Guizhou, I used the real geography of the Karst landscape and layered it with speculative ideas from media theory—like Bratton's Stack or Morton's hyperobjects—to create a narrative that feels both grounded and slightly disorienting. That tension between the known and the imagined invites audiences to question what's real, what's hidden, and what might come next.

So, in my process, I don't try to separate fact and fiction—I let them intertwine each other. Fiction opens up space for imagination and critique, while research keeps me connected to the realities I want to engage with. The balance happens through constant iteration and reflection.

Green Election Urban Mining, 2023 © Hanqi Li

Green Election Urban Mining, 2023 © Hanqi Li

Technology is both a tool and a subject in your work. How do you see digital and generative art evolving in the context of environmental awareness?

Lately, I've seen a huge rise in AI-generated art—it's become almost inescapable. You see these algorithmically produced images everywhere, often presented as something magical or even revolutionary. While I understand the excitement around the aesthetics and accessibility of these tools, I think what's missing from most of the conversation is a deeper awareness of what's behind them—not just in terms of data and algorithms, but the physical infrastructure that supports them.

AI doesn't exist in a vacuum. It runs on massive servers, relies on energy-intensive training processes, and depends on global networks of extraction, labour, and waste—from mined rare earth minerals to outsourced data labelling and the eventual e-waste these systems generate. So, while AI-generated images may appear "immaterial," they're built on a very material foundation.

That's what I find most urgent right now—not just exploring what these technologies can do but asking what they cost and who or what pays the price. As an artist working with digital and generative media, I think it's important to stay critical, slow down, and consider the environmental and ethical impact of the tools we use. The digital world isn't separate from the natural one—they're completely entangled. And in my practice, I try to make that visible.

Having exhibited at Ars Electronica and been recognized by the Lumen Prize, how has the international reception of your work influenced your perspective as an artist?

These international exhibition experiences not just as validation but as a moment to reflect on how my work connects with audiences beyond its original context. My projects often deal with very specific sites, like Guiyu or Guizhou, and explore themes that are deeply rooted in Chinese environmental and technological realities. So I used to wonder: will international audiences understand or relate to these issues? But what I've found is that many of the questions I'm asking—about digital infrastructure, environmental cost, and the hidden systems behind our technologies—are actually shared concerns, even if they take different forms around the world.

During Ars Electronica Festival, I had the chance to speak with many visitors about my project Down to the Underground Karst Landscape. I was surprised and grateful for how curious people were about Guizhou—not just as a technological site but as a natural landscape. Many were struck by the power and scale of its geological formations. One artist from Europe told me that the geographic conditions in Guizhou reminded them of how Finland's natural features have also been used for data centres—because of the cool temperatures and underground potential. That kind of exchange really opened up new ways for me to think about my work, not just as a localized investigation but as part of a broader, planetary conversation.

The international response helped me realize that these are not just "local" or "regional" problems—they're part of a global network of entanglements. It's also encouraged me to be more confident in blending specificity with abstraction and research with imagination.

Green Election Urban Mining, 2023 © Hanqi Li

Lastly, what upcoming projects or ideas are you currently exploring, and is there a new direction you're excited to pursue?

Right now, I'm continuing to explore the environmental impact of emerging technologies but shifting my focus slightly toward the relationship between AI systems and planetary-scale resources. With the rapid growth of generative AI, I've been thinking a lot about the hidden cost of "training" intelligence—both in terms of data and energy but also in terms of extraction, labour, and waste. I'm interested in asking: what does it take, materially and ecologically, to make something "smart"?

I'm also beginning research into the geological and infrastructural layers behind digital ecosystems—almost like a continuation of the Karst project, but expanding to look at sites where computation is literally embedded into the land. This might involve new installations or field recordings that combine speculative storytelling with real-world geographic data.

At the same time, I'm curious about how to create more participatory or collaborative elements in my work—inviting audiences not just to observe but to question and even contribute. I don't have all the answers yet, but I'm excited by the idea of building work that is less about presenting information and more about opening a shared space of reflection around the technologies shaping our future.