10 Questions with Anastasia Egonyan

Al-Tiba9 Art Magazine ISSUE18 | Featured Artist

Anastasia Egonyan (b. 1987, Kharkiv, Ukraine) is a visual artist of Ukrainian and Armenian descent based in Berlin. With over a decade of experience in photography, she has expanded her practice to incorporate textiles and found objects, creating a dynamic interdisciplinary approach. Anastasia's work has been showcased in both solo and group exhibitions at international galleries and art institutions in Amsterdam, Zurich, Yerevan, and Berlin. Her art reflects a journey of reconciling fragmented ancestry and nomadic experiences in the search for "home" and identity that includes living and working in Hungary, Ukraine, Armenia, Poland, and Germany over the course of her life.

Anastasia Egonyan - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Anastasia's family history traces back to Artsakh and features significant historical figures—a heritage that quietly fuels her investigation of ancestral narratives. Her focus on female resilience serves as a framework for Anastasia Egonyan's rapidly evolving body of work. The artistic process is deeply rooted in the exploration of the culture and history of Armenia with a bold approach to visual transformation and profound psychological self-reflection. Anastasia integrates textiles and recycles available materials/artefacts, repurposing them to create new contexts and meanings. Her practice includes photography, image transfer techniques, traditional Armenian artisan techniques and materials (i.e., sheep wool and blanket-making), and the delicate use of pearls. By incorporating Armenian words and common phrases into her creations, she preserves and celebrates her cultural identity. Anastasia draws deep symbolism from the simplicity of everyday life while honouring women's strength through historical and cultural perspectives.

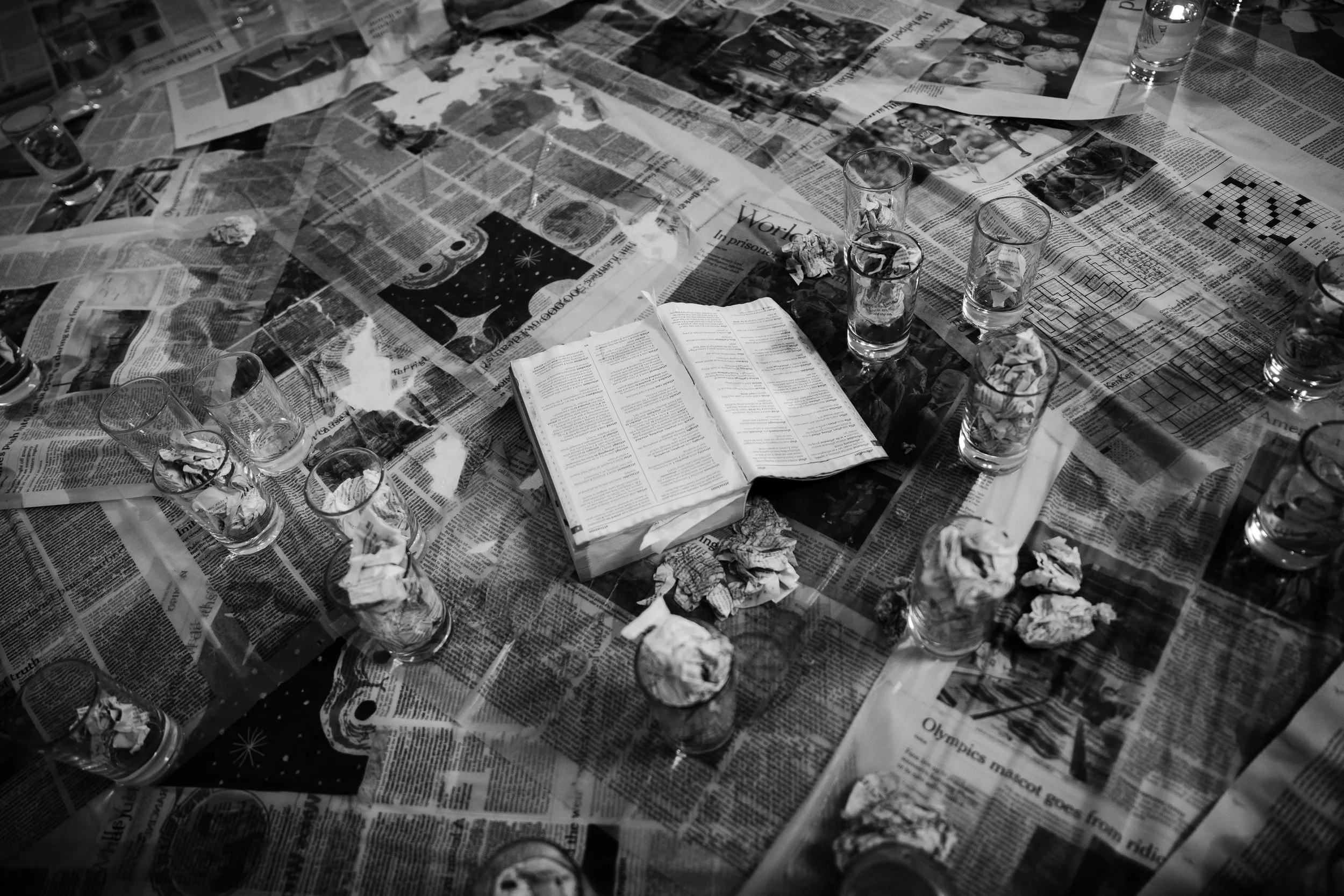

I take your pain, self-published zine, 2024 © Anastasia Egonyan

AL-TIBA9 ART MAGAZINE ISSUE18

INTERVIEW

Please tell us a bit about yourself. You have an interesting family history and personal journey. Who are you, and how did you develop into the artist you are today

I was born in Ukraine in 1987, but my family history begins in a distant and beautiful land called Armenia. My ancestral line traces back to one of the prominent Armenian historical figures, Melik Yegan, who once ruled in the village of Togh,in the Hadrut region of Artsakh. My great-grandfather, Pavel Yeganyan, was the last in our family to live in Artsakh—he was tragically murdered by the communists in 1928 for resisting the regime. After his death, my family was forced to seek refuge elsewhere. My grandfather was adopted by a family friend and eventually relocated to Ukraine.

Artsakh, though unrecognised internationally, was an independent Armenian land marked by deep wounds and ongoing struggle. Today, it is occupied by another state due to the recent political conflict, which led to the forced displacement of its Armenian population. This loss—both personal and collective—continues to shape the emotional core of my artistic practice.

At the heart of it all is always love—an energy that drives everything I do. It's the strongest and most meaningful force I know, and the source of my deepest dedication. Love unfolds in many forms: joy, romanticism, pain, despair, hope, and passion. These layered emotions hold the truth—and it's that truth I speak through my work.

ցավդ տանեմ - I take your pain, textile, 220 x 320 cm, 2024 © Anastasia Egonyan

Your work is deeply rooted in identity, ancestry, and displacement themes. How has your journey across different countries shaped your artistic approach?

Living in different countries has given me a broader perspective on how the world functions. It's fascinating to realise that while people may seem different everywhere, at their core, they are not. Rituals and habits may change, but human nature remains the same.

We often overlook how society shapes our perception of reality and how morality shifts from one place to another. Yet, beneath all these differences, I've found that emotions are universal. Pain, joy, dilemmas—we all experience them, no matter where we come from. We may speak different languages, but we share the same emotional one.

That's what draws me to visual art and the themes I explore. Berlin, more than any other place, has shaped me in the context of art. It's a city that holds the most honest trace of human existence—a landscape marked by both negligence and desperate hope. Berlin is also naked, brutal, and emotionally unavailable. It's been painful to experience—and a joy to resist.

You started with photography and later expanded into textiles and found objects. What prompted this shift, and how do these materials help you convey your ideas?

I started photography at 16 as a compromise for not being able to attend art school. At the time, I was dealing with health issues and uncertainty about where I could build a life—whether in Hungary or somewhere else. Formal education felt out of reach, so I saved up for a film camera and taught myself the basics of composition. Over time, my persistence turned into passion, and I eventually became a full-time photographer.

Many years later, I realised I was no longer willing to compromise. I completed a painting apprenticeship in Berlin and spent the following years developing my voice through practice and experimentation. In time, I discovered that a canvas alone wasn't enough—I was drawn to diverse materials, and my passion for layering and combining them naturally led me to where I belong today.

Ջան - Jan, Textile (raw cotton, muslin), sheep wool, digital photography transfer, natural pearls, 78 x 44 cm, 2025 © Anastasia Egonyan

Ցավդ տանեմ - Tsavd tanem, Textile (raw cotton, muslin), sheep wool, manual photography transfer, natural pearls, 78 x 43 cm, 2025 © Anastasia Egonyan

Female resilience is a core theme in your practice. How do you express this concept visually, and are specific historical or personal influences guiding this focus?

I am deeply and genuinely inspired by the lives and stories of strong women—who, in my experience, are far more present around us than we often realise. History highlights only a few artists, scientists, and women figures who've shaped culture and society, but their voices are still too few. I believe there's room for more—for different perspectives, for new approaches, for unheard truths.

Often, the most vulnerable and heartbreaking stories of resistance are shared quietly, in private conversations behind closed doors. We still live within the framework of societal expectations. We are raised differently, taught to compromise, and pushed to find our paths despite the roles assigned to us. We are objectified, exposed to violence, and yet shamed for expressing sexual desire.

It's a complex and painful reality—one that lies just beneath the surface, visually hidden under thick layers of silence and shame.

Your work often involves repurposing materials and artefacts. How do you select these objects, and what role does transformation play in your creative process?

I find great joy in searching through nature—it's a generous, unconditional source of materials and inspiration. I feel the same towards vintage objects. When I come across old things, I can't help but imagine the stories they carry, the lives they once touched. I wonder who owned them, why they left, and whether they've been forgotten.

In many ways, I'm a materialist. There's a joy for me in exploring what we're capable of making. Yet everything has its own timeline. Every story ends. Or does it? I like to believe that by using found objects, I give them new meanings. Ihonour the life they had before me, while guiding them into my own. But in the end, it's still an illusion. Everything will disappear eventually—and there's a certain beauty in that too. It reminds me to cherish the present moment and to live fully.

In the silence of memories I found the roots of my tree, 2024 © Anastasia Egonyan

Armenian traditions and materials also play a significant role in your work. Can you discuss the importance of incorporating elements like sheep wool and pearls into your art?

I am deeply fascinated by the beauty of everyday life. The base of many of my works is an Armenian wool blanket (or duvet), traditionally stuffed with sheep's wool. These blankets are more than practical objects—they carry layers of memory and tradition. The process of making them—washing, combing, sun-drying the wool, sewing, and repeating these steps each year—is a communal ritual, shared among the women of the household. It's a practice rooted in love and care, passed down through generations.

During my last trip to Armenia, I discovered a pearl and silver necklace, likely from the 19th century. This delicate piece led me to explore the cultural symbolism of pearls. In Armenian folklore, pearls represent purity, beauty, and femininity. Historically, they adorned bridal headpieces, necklaces, and embroidered garments. Natural, fragile, and precious—they embody the quiet tenderness I seek in my work.

You also integrate Armenian words and phrases into your pieces. How do language and text enhance your storytelling, and what kind of dialogue do you hope to create with your audience?

Language reflects the soul of a society—and the Armenian language is full of love. There's a poetic tenderness woven into everyday conversations that I haven't encountered in any other language I know. Phrases like "Ցավդ տանեմ" ("I take your pain") or "Մեռնեմ ջանիդ" ("I will die on your body") reveal just how deeply love can be felt and expressed. It's not just romantic—it's part of the spirit of the people: to feel intensely, to love fiercely, and to carry one another's sorrow without hesitation.

This spirit—of unconditional love, of quiet acceptance, of sharing pain as if it were one's own—touches me deeply. It speaks to something in me that has long existed in exile, in denial. We've grown cold to one another, even in our closest relationships, when in truth, we could be speaking love every day. The struggle often lies not in politics or distance but in the space between two people. And yet, if we simply shared our bread and chose to accept one another, life could be so much kinder.

Your shadow of my light, Textile, 128 x 55 cm, 2025 © Anastasia Egonyan

Virgin Mary with Child, Textile, 63 x 42 cm, 2025 © Anastasia Egonyan

Mother of All Living, Textile, 2025 © Anastasia Egonyan

Է, textile, 94 x 45 cm, 2025 © Anastasia Egonyan

Having exhibited in cities like Amsterdam, Zurich, Yerevan, and Berlin, how do different cultural contexts affect the reception and interpretation of your work?

I enjoy exploring different environments—some are open and accepting, while others are more resistant to new perspectives. This contrast creates both a challenge and a sense of purpose. What excites me most is seeing support for Armenian themes and female-driven narratives in diverse contexts.

In Berlin, the art scene is particularly unique and international. A key space for me has been HK Art Gallery, a female-led organisation that represents my work. It plays a special role in bridging contemporary Armenian artists with a classical collection of established masters, creating a dialogue between past and present.

Is there anything else you would like to experiment with or incorporate into your practice in the future? Is there any new medium or technique you would like to implement?

I'm always open to experimentation—because I believe there's no true freedom of expression when you confine yourself to a single way of thinking. I'm certain that new ideas and influences will continue to shape my work. Urban environments already find their way into my practice, and I'm eager to keep exploring new places and cultures throughout my life.

Է, textile, 94 x 45 cm, 2025 © Anastasia Egonyan

Lastly, what are you currently working on, and how do you see your practice evolving in the coming years?

I continue to explore the subject of my ancestry, the influence of religion, traditions, and the role of women. These themes often raise complex questions—ones that may seem ordinary in one context but controversial in another. It's this tension that keeps me engaged.

Looking back, I see how my current approach—combining materials, photographing, working with textiles, and my childhood habit of cutting up old magazines to make collages—has grown from years of exploring these elements independently. Only now have they come together organically, forming the visual language I work with today. For me, the joy of life lies in staying open, continuing to learn, and allowing my practice to evolve with me.