10 Questions with Hou Guan-Ting

AL-TIBA9 ART MAGAZINE ISSUE18 | FEATURED ARTIST

Hou Guan-Ting (侯冠廷), born in 1999, explores the relationships between time, the body, and craftsmanship. Through intricate textile techniques and layered textures, his work examines how material and memory intertwine within woven structures.

whitechicken64013.wixsite.com/houguanting | @whitechicken_fiber

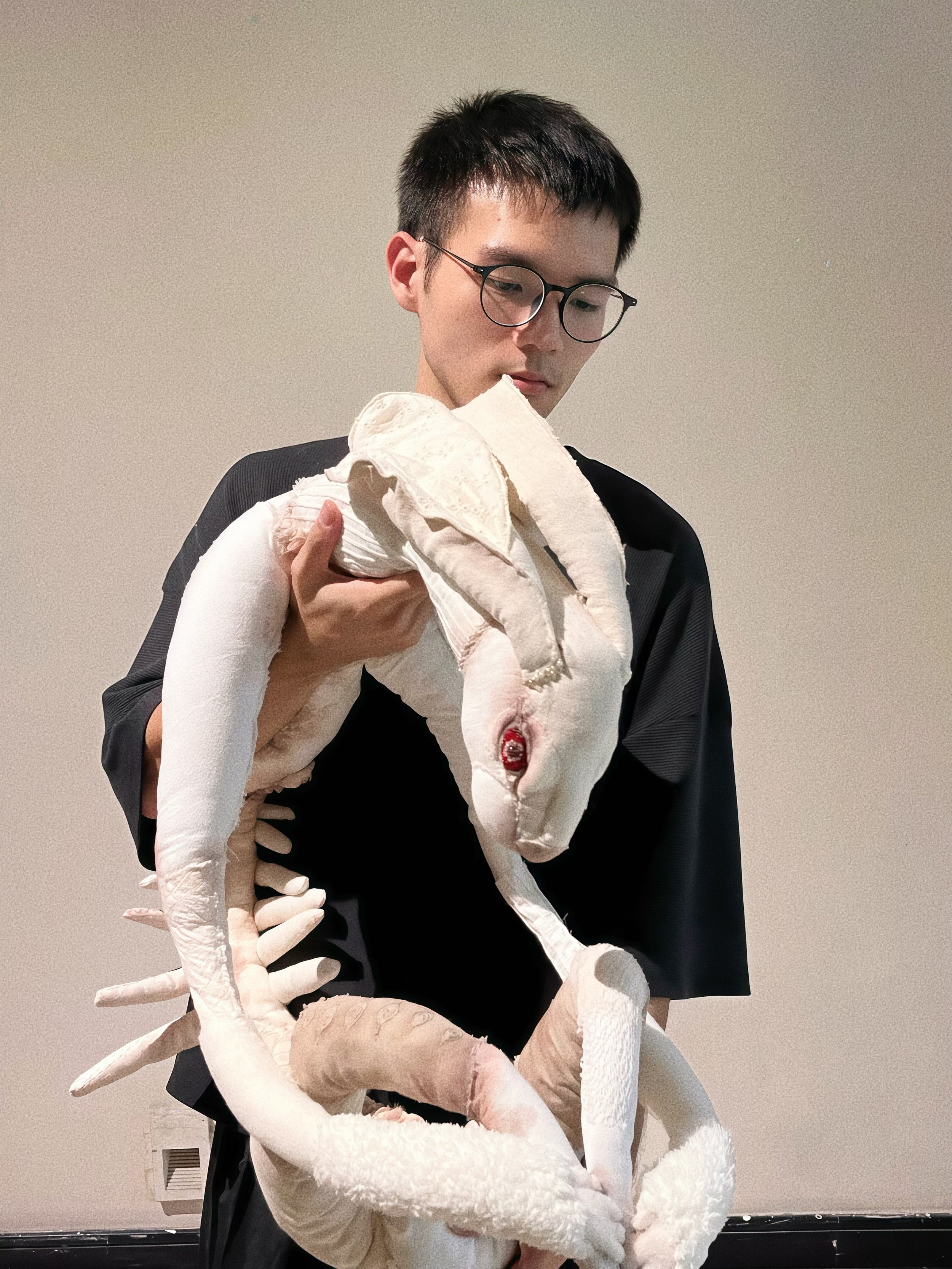

Hou Guan-Ting - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Hou Guan Ting draws inspiration from roadkill and the process of bodily decay, initially captivated by the external characteristics of decomposing forms. Hou observes how decay alters texture and image over time, a phenomenon that seems both time-sensitive and timeless. Using the language of traditional crafts like embroidery and patchwork, Hou deconstructs and reinterprets subjects deemed ugly or unpleasant by society, transforming them into works of art. His pieces compel audiences to confront these uncomfortable details, urging them to explore dark corners they might otherwise avoid. Through his art, Hou challenges society's tendency to obscure death and violence, as the media often does, by filtering such images into vague and sanitized forms. Instead, he translates the raw and distressing into vivid, tactile creations, stripping away moral "mosaics" and replacing them with colourful textures. This approach allows viewers to confront death in a buffered, layered manner, prompting deeper engagement and contemplation.

Hou reflects on how modern life, dominated by fragmented media and overstimulation, has dulled people's capacity for focus and introspection. In contrast, his art invites a slower, more mindful experience. His creative process is deeply immersive, amplifying his senses as he contemplates the tactile and sensory dimensions of his work. By examining the remains of roadkill—broken bones, sticky fur, and decaying forms—Hou enters a meditative state where time slows, and the noise of the world fades. For Hou, art serves as a key to reclaiming a sense of presence and amplifying awareness in a world that rushes past life's essential truths. His works encourage viewers to pause, reflect, and confront the realities of death and decay, offering a space for quiet contemplation amidst the chaos of modern existence.

Lazy bone, cotton, beans, embroidery thread, ocher powder, ink, dimensions variable, 2022 © Hou Guan-Ting

AL-TIBA9 ART MAGAZINE ISSUE18

INTERVIEW

What is your background, and when did you first become interested in art-making?

I don't have any particularly special background. Since childhood, I was the kind of odd kid who preferred walking with my head down, watching the ground beneath my feet. My heart was always filled with inexplicable emotions, nameless sensations that I felt an overwhelming need to record. Without realizing it, that urge carried me to where I am today.

What initially drew you to fibre art, and how do you see it fitting within the broader landscape of contemporary art?

I love how fibre is both fragile and resilient, pure yet easily imprinted. Time leaves its marks effortlessly on fabric—whether through the stains of humidity and warmth or the wrinkles left by the pull of a hand. These are warm, deeply human qualities.

Fibre has always held a unique position in contemporary art. Because it is so intimately tied to the everyday, it is often taken for granted and overlooked. But that is precisely why I find it so compelling as a medium. I want to harness its softness and subtlety to create works that cannot be ignored. To me, that paradox—where something gentle can hold immense power—is the most beautiful image of all.

Deformed, nylon, cotton, linen, gauze, embroidery, pulp, bark, seiryutai ink, 127x56 cm, 2021 © Hou Guan-Ting

How has your time at Tainan National University of the Arts shaped your research and artistic exploration?

During my graduate studies, I encountered the concept of "物の哀れ(mono no aware)"—a sensitivity to the transient, ephemeral nature of things, tinged with a melancholic beauty. It is not simply sadness; it carries a profound reverence for impermanence, a quiet awareness of life's fleeting essence.

My university is nestled in the mountains, where daily life unfolds in close conversation with nature and art. Living in such an environment sharpened my sensitivity to subtle changes in my surroundings. I became acutely aware of how time flows, even when I do nothing. This realization compelled me to document the fading, the withering—to transform them into a part of my own existence.

Your work is deeply inspired by roadkill and bodily decay. What led you to explore these themes, and how has your perspective on them evolved?

In Taiwan, where I grew up, it is not uncommon to see small animals crushed by passing cars. At first, I was simply drawn to the visceral imagery—the twisted bones, the ruptured intestines, the fur stained with bodily fluids. But as I crouched down and observed them closely, I experienced a force that was both brutal and undeniably alive, terrifying yet filled with raw vitality.

Over time, as I completed more works, I came to realize that the grotesque, contorted, and decaying forms I meticulously depicted were, in some way, reflections of myself. A part of me longed to remain unnoticed in the shadows, yet another part yearned for attention. Through constant creation and self-examination, I began to understand that my imagery was not merely about death or violence—it was about existence itself.

Deformed (detail), nylon, cotton, linen, gauze, embroidery, pulp, bark, seiryutai ink, 127x56 cm, 2021 © Hou Guan-Ting

Deformed (detail), nylon, cotton, linen, gauze, embroidery, pulp, bark, seiryutai ink, 127x56 cm, 2021 © Hou Guan-Ting

Your work challenges society's sanitized portrayal of death and violence. How do you navigate the balance between discomfort and engagement in your artistic practice?

People only become aware of movement when they pause, and death is the starkest reminder of this truth. We are all bound to vanish, yet most choose to look away. My work does not aim to confront the viewer with blatant gore or brutality. Instead, I build a bridge—a space where they can observe from a distance, navigating the tension between clarity and ambiguity.

Through slow, intricate techniques like embroidery and hand-stitching, I envelop themes of violence and mortality in textures that feel soft, almost tender. A single thread, woven carefully, can gently stir the harshness of reality—like tracing the contours of a petal as it wilts over time. I do not wish to force an encounter with death; rather, I want to create an irresistible pull, leading viewers into my world before they realize what they are truly seeing.

In an era where everything is overly clear, overly rational, and overly linear, I attempt to inject a kind of distorted romanticism—an ambiguous space drifting between reality and dream. My hope is that viewers project their own emotions onto my work rather than passively accepting a fixed narrative.

Textures and slow, tactile processes seem essential to your work. What is your creative process like, and how does it influence the final result?

For me, texture and tactility are not just visual elements; they are keys to evoking memory and guiding perception. I often manipulate the surfaces of materials—applying layers of glue to alter reflectivity and stiffness, scraping fabric with an awl to create delicate scars of time, or using burning and soaking techniques to push materials beyond their original state. These are not acts of destruction but ways of allowing the material to "speak," revealing traces of time, touch, and even loss.

My process is slow, unfolding through endless experimentation. Each material reacts differently under changing conditions, and those unexpected transformations often become the core of my next piece.

The textures that captivate me at any given moment are deeply connected to my emotions and state of mind, making my work feel like a diary—an ongoing record of my evolving dialogue with time and materiality. In this sense, my works never have a true "final" form; they exist as fluid entities, always shifting, reflecting the life they hold within.

Mythical III, cotton, nylon, velvet, yarn, beans, sequins, ocher powder, Seiryutai ink, 45x38x34 cm, 2024 © Hou Guan-Ting

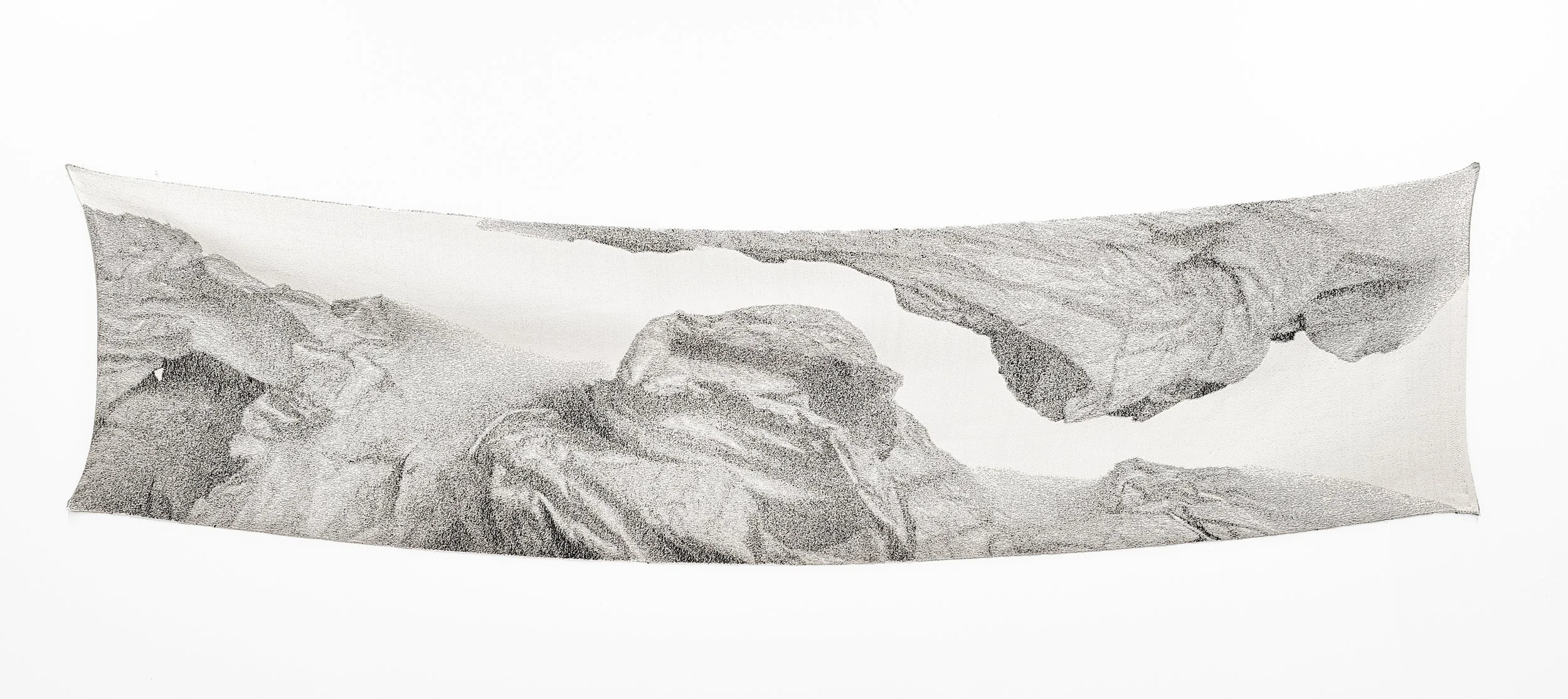

Mythical l (detail), cotton, lines, beads, pigments, glue, seiryutai ink, 158x112 cm, 2023 © Hou Guan-Ting

Mythical l (detail), cotton, lines, beads, pigments, glue, seiryutai ink, 158x112 cm, 2023 © Hou Guan-Ting

In what ways do you hope your audience reacts to and interacts with your art? Are you looking to provoke, comfort, or create space for reflection?

I believe that modern life moves too fast. Information floods in like a tidal wave, sweeping away focus and thought, leaving only fatigue and apathy. Screens flash before our eyes, numbing our senses, reducing us to passive consumers of fragmented content. We know this is happening—we feel the erosion of our inner worlds—but we choose to ignore it because that makes survival easier.

In such a world, I hope my work acts as a pause button. I want viewers to slow down and return to a state of pure perception. I do not seek to capture attention through shock or provocation but rather to gently draw them into a space of stillness. Perhaps through texture, light, or color, an emotion long buried will begin to surface—a feeling they once knew but lost in the rush of modern life.

My work does not aim to provide answers. It is a space, an opening—an invitation to sit with oneself, to feel time, to feel presence. In a world that moves too fast, I wish for my art to be a refuge where the forgotten can be reclaimed.

Your art requires deep focus and immersion. How does working in this slow, meditative way contrast with the fast-paced, fragmented nature of modern life?

When I create, it feels like stepping into a solitary room where time moves so slowly that even a torrential downpour outside becomes inconsequential. The raindrops break apart fragments of life, blurring into damp memories, while this mental retreat offers me a shelter—a space to pause and anchor my emotions. As I stitch, thread by thread, I slowly mend the gaps in my memories. Yet, the moment I step outside, reality whispers in my ear: "How can an artist prove their worth? How do we justify the act of creation as something meaningful?" This is a question I often struggle with.

Returning to the real world, I sometimes feel like I am being swept away. Society prioritizes utility above all else—efficiency drives progress, technology refines every material need, and people, over time, adapt, conform, and eventually lose themselves. In this grey, mechanical city, we are bound by the standards of usefulness, moving through life like cogs in a machine—walking the same paths, repeating the same routines, and becoming willing slaves to the system. Anything deemed "useless" is seen as a burden, like a vestigial organ, an evolutionary leftover that impedes progress. But this way of thinking is a form of violence—a quiet, insidious brutality. People today are impatient, restless, and unable to engage with anything that lacks immediate function or tangible reward. They are propelled forward by the pace of the era as if cursed like the girl in Andersen's fairy tale, forced to dance in her red shoes until she collapses from exhaustion.

The gears of the city keep turning, and a sense of disillusionment and helplessness has become the default state of modern life. Curiosity about the "useless" is slowly fading, replaced by a thirst for efficiency and context-free convenience. And yet, people still feel an unshakable emptiness, a longing for something fleeting and intangible. In chasing speed, we neglect the long history of art, allowing its quiet resistance to be crushed by the relentless push for quantifiable value. In this era of numbers and metrics, I feel like a limping rabbit, caught between the wild beasts of blind ambition and the mirage of materialism, struggling to survive.

It is precisely in times like these that art, in all its openness and multiplicity, becomes a necessary form of resistance—challenging exclusivity, singular thinking, and the obsession with utility. Now, more than ever, the importance of the "useless" is clear.

Mythical l, cotton, lines, beads, pigments, glue, seiryutai ink, 158x112 cm, 2023 © Hou Guan-Ting

Looking ahead, are there any new materials, techniques, or ideas you're excited to explore?

Recently, I have been working with pig skin. Compared to fibre, leather carries a more immediate bodily presence, a direct evocation of mortality. My challenge now is to weave these materials together—to distil my inner visions into something tangible, something that serves as a key to unlocking sorrow and connection.

During my artist residency in Kyoto, I spent months wandering between temples, lying by the riverbanks, watching the vast sky and trembling willow leaves. Just feeling time pass. In that quiet stillness, I realized—this is the atmosphere I long to create.

Moving forward, my challenge is to translate these deeply sensory, almost mist-like, elusive emotions into tangible artistic expression—not merely creating a vessel, but distilling and breathing life into each piece, imbuing them with a soul of their own.

Lastly, what are you working on now? Do you have any new projects you'd like to share with our readers?

I am still creating and striving toward the atmosphere that resonates within me, and my artistic trajectory continues to evolve with the encounters and experiences of life. I believe that only by being honest with my own creations can I truly move my audience. If you find my interview intriguing or have any thoughts you'd like to share after reading it, feel free to contact me via email.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.